ABSTRACT

-

Objective

Propolis has been suggested as a complementary therapy for improving glycemic control and lipid metabolism. However, evidence from clinical trials remains inconsistent. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to provide a clear and updated assessment of the effects of propolis supplementation on fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profiles in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and metabolic syndrome (MetS).

-

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted on the PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases through December 2024 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the impact of propolis supplementation on FBS and lipid parameters. Eligible data were pooled using a random-effects model, and weighted mean differences (WMDs) were calculated as pooled effect sizes.

-

Results

A total of 12 RCTs were included, encompassing 736 participants. Propolis supplementation significantly reduced FBS (WMD, −12.08 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval [CI], −19.13 to −5.04; P=0.001) and triglyceride (TG) levels (WMD, −25.40 mg/dL; 95% CI, −44.21 to −6.59; P=0.008) without significantly affecting the levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

-

Conclusion

These findings suggest that propolis supplementation may modestly improve glycemic control and reduce TG levels in individuals with T2DM and MetS. However, the limited number of available studies and relatively small sample sizes highlight the need for large, high-quality RCTs to verify these findings and clarify the metabolic effects of propolis.

-

Keywords: Propolis; Bee glue; Diabetes mellitus; Metabolic syndrome; Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a common endocrine disorder wherein the body either cannot use insulin effectively or the pancreas produces insufficient insulin [

1,

2]. The global prevalence of T2DM is rising rapidly, and the disease is forecasted to affect 642 million individuals by 2040 [

3]. In addition to affecting the health of individuals, T2DM imposes an onerous burden on healthcare systems [

4]. The costs of treating T2DM and its complications, such as cardiovascular disease, kidney damage, nerve disorders, and eye problems, are substantial [

5]. Metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by obesity, high cholesterol, insulin resistance, and hypertension, is linked to an increased risk of developing T2DM [

6]. Current strategies for managing T2DM and MetS include dietary modifications, regular exercise, weight loss, and medication [

7,

8]. Although effective, these approaches are often challenging to maintain over the long term because lifestyle changes can be difficult and medications may cause side effects [

9-

12]. This drawback underscores the need for complementary strategies that can support individuals alongside standard treatments.

Natural supplements are increasingly gaining attention for their health benefits [

13,

14]. Honeybee products, such as propolis, have shown promise owing to their bioactive compounds, accessibility, and minimal side effects [

15-

17]. Propolis, a sticky substance that bees use to protect their hives, has been used in traditional medicine for centuries to aid healing, reduce inflammation, and combat infections [

18,

19]. Contemporary studies suggest that it may also help control blood sugar [

20], improve lipid profiles [

21], and positively affect anthropometric measurements [

22] and blood pressure [

23].

Several clinical trials have investigated the effects of propolis on glucose and lipid levels in patients with T2DM and MetS [

24-

35], but the results remain inconsistent. Some studies have reported improvements in metabolic parameters [

30,

32,

34], while others have reported no significant changes [

29,

31,

35]. Given these conflicting findings, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to clarify the effects of propolis supplementation on blood sugar and lipid levels in individuals with T2DM and MetS.

METHODS

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [

36]. To ensure high methodological quality, we also adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

37].

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated propolis supplementation in individuals with T2DM or MetS. The PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were searched for studies published up to December 31, 2024. The following search terms were used: “propolis,” “bee glue,” “bee bread,” “insulin resistance syndrome,” “syndrome X,” “metabolic syndrome,” “Reaven’s syndrome,” “type 2 diabetes mellitus,” “diabetes mellitus,” and “hyperglycemia.” MeSH terms, truncations, variations, and acronyms were applied to maximize search coverage. The reference lists of all included studies, as well as relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses, were manually screened to identify additional eligible trials.

Study selection

All identified articles were initially screened by title and abstract, followed by full-text review to determine eligibility. Two independent authors screened the studies separately, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussions with a third reviewer. Literature screening was performed using the EndNote X8 reference manager (Clarivate). The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) RCTs conducted in adults (aged ≥18 years) with T2DM or MetS; (2) investigation of propolis supplementation for a minimum duration of 1 week, with a control or placebo group included in the study design; (3) reporting of at least one relevant outcome, such as fasting blood sugar (FBS) levels or lipid profiles; (4) studies published in English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies conducted in children, pregnant women, or lactating women; (2) studies reporting insufficient data; (3) trials that assessed propolis in combination with other compounds; (4) gray literature, including theses and conference abstracts. If the same trial was covered by multiple publications, the most comprehensive report was selected as the main reference.

Data extraction

Data were collected from all eligible articles using a standardized extraction form. One researcher performed the initial extraction, and the extracted data were independently verified by two additional reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The extracted data included participant characteristics (sample size, gender, and age), study details (author, year, country, propolis dose and formulation, type of intervention, and treatment duration), main outcomes (FBS, total cholesterol [TC], triglyceride [TG], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C]), and key information for risk of bias assessment. For studies that reported data only in graphical form, numerical values were obtained using GetData Graph Digitizer version 2.26 (Informer Technologies Inc.). The corresponding authors were contacted for clarification in cases of missing information.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool [

36]. This tool examines seven domains: (1) sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel, (4) blinding of outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective outcome reporting, and (7) other potential sources of bias. Each domain was categorized as having a low, unclear, or high risk of bias. The evaluation was conducted independently by two researchers, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

All analyses were conducted using STATA ver. 11.0 (StataCorp.). Outcomes are reported as weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), calculated using the generic inverse variance method. A random-effects model was utilized to account for the expected heterogeneity across studies. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the I² statistic, with values greater than 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the potential effects of intervention duration and study location on the outcomes. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the leave-one-out method to assess the robustness of the findings. Publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s test, and a P-value ≤0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Literature search

Searches conducted on four electronic databases yielded a total of 487 records, of which 373 remained after duplicates were removed using EndNote. Title and abstract screening resulted in the selection of 26 articles for full-text assessment. Of these, 14 studies were excluded for the following reasons: investigating propolis in combination with other substances (n=2), no reporting on the outcomes of interest (n=2), absence of an appropriate control group (n=1), no participation of individuals with T2DM or MetS (n=9). Ultimately, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in

Fig. S1 [

24-

35].

Overall, 12 RCTs published between 2015 and 2024 and encompassing 736 participants were included in this meta-analysis [

24-

35]. According to Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool [

36], two studies were rated as having fair quality [

28,

35] and one as having weak quality [

27], while the remaining trials demonstrated good methodological quality [

24-

26,

29-

34]. Detailed characteristics of the studies and their quality assessments are presented in

Table 1 and

Table S1, respectively.

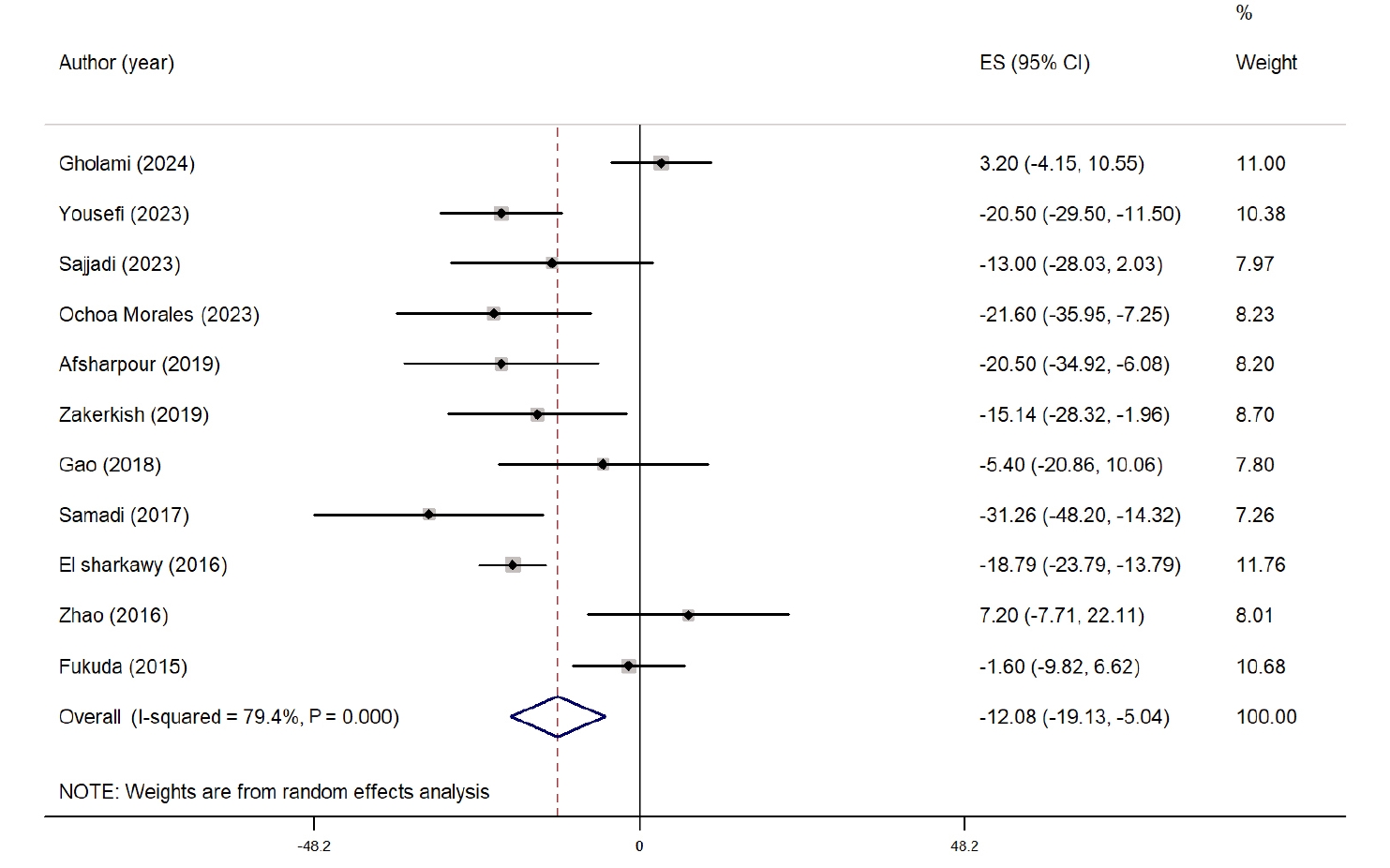

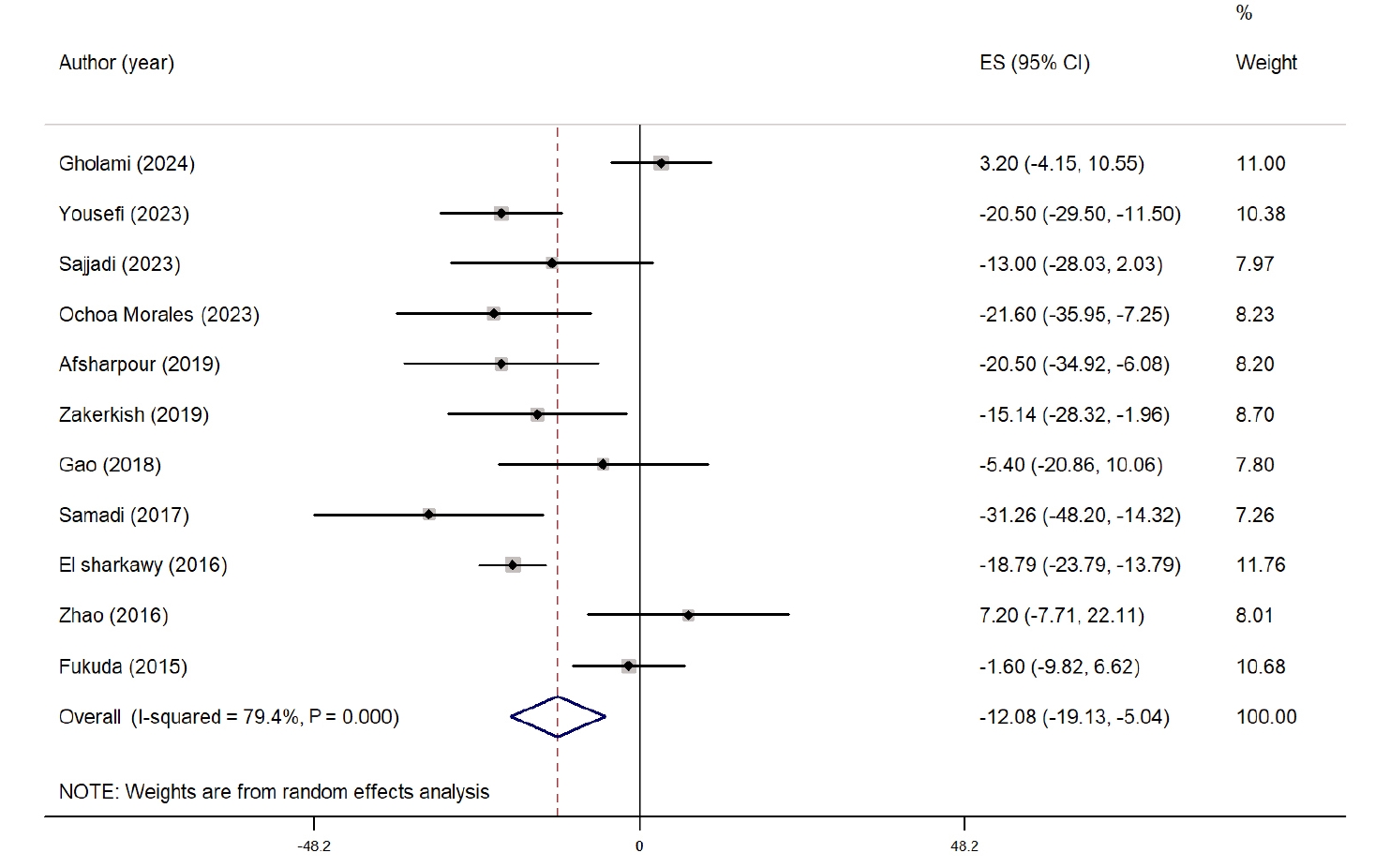

The overall effect of propolis on FBS is presented as a forest plot in

Fig. 1. Eleven studies evaluated the impact of propolis supplementation on FBS [

24-

28,

30-

35]. Overall, propolis significantly reduced FBS compared with the control group (WMD, −12.08 mg/dL; 95% CI, −19.13 to −5.04; P=0.001). Despite considerable heterogeneity among the studies (I

2=79.4%, P˂0.001), sensitivity analysis showed that the results were not influenced by any single study. Subgroup analysis revealed a significant reduction in FBS only in studies with >8 weeks of intervention and in those conducted in West Asian countries. However, heterogeneity remained high in all subgroups. The subgroup analysis results are presented in

Table S2.

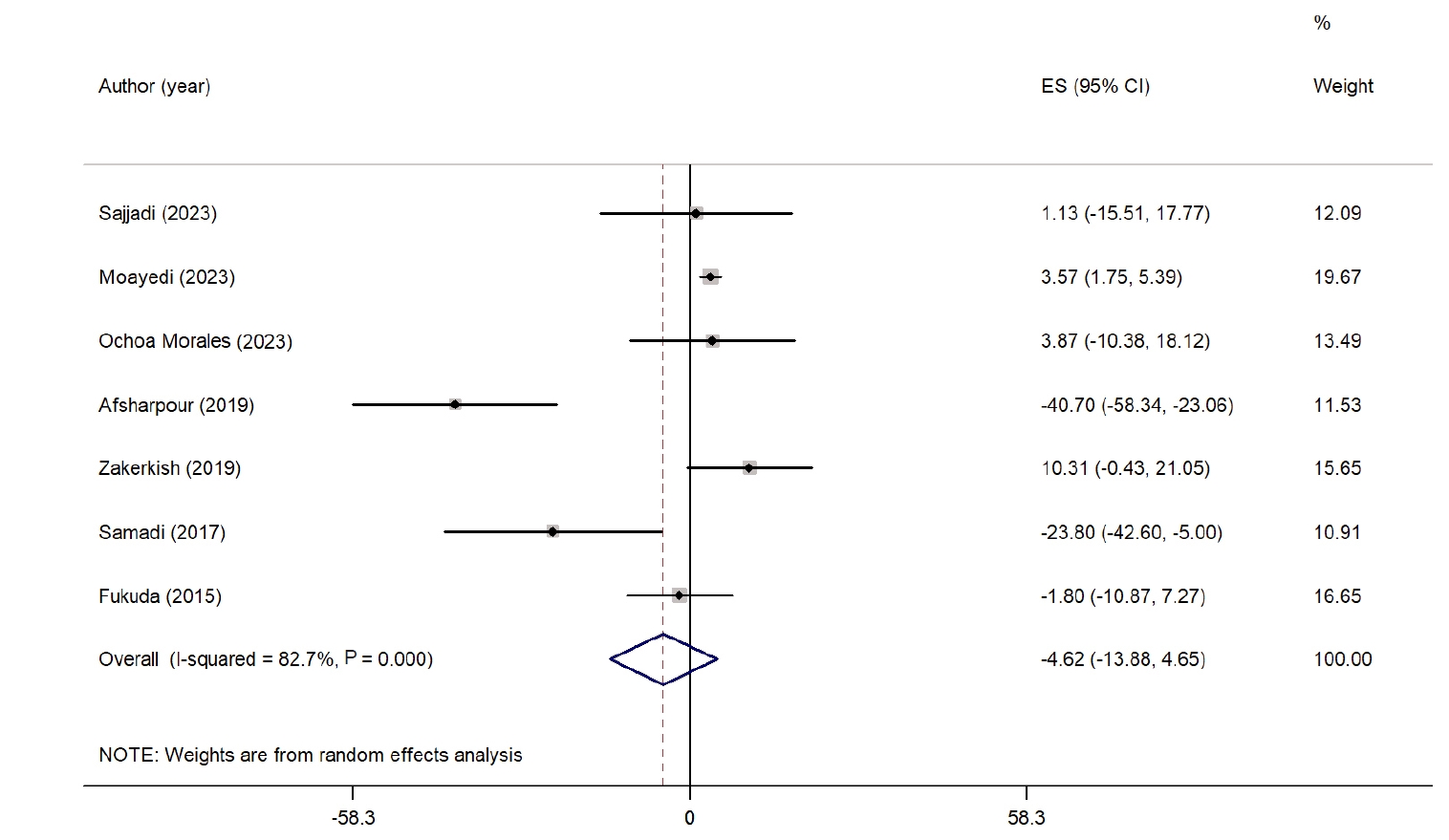

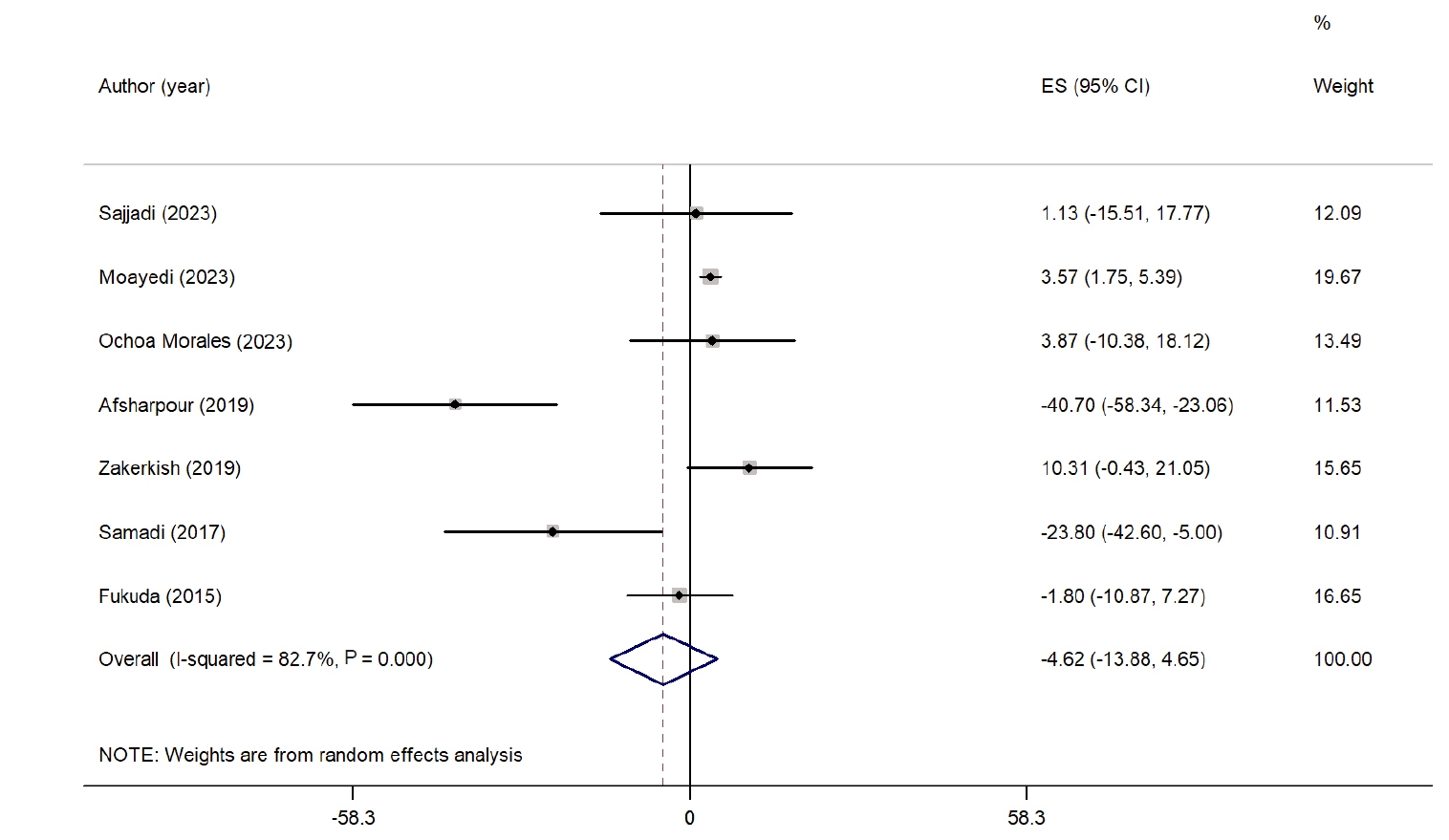

Fig. 2 depicts the overall impact of propolis supplementation on TC. Seven studies examined the effect of propolis on TC [

24,

26,

29-

32,

34]. The findings indicate that propolis supplementation did not lead to a significant reduction in TC compared with the control group (WMD, −4.62 mg/dL; 95% CI, −13.88 to 4.65; P=0.32). Considerable heterogeneity was noted among the studies (I

2=82.7%, P˂0.001). Sensitivity analyses showed that the overall results were stable and not influenced by the exclusion of any single study. Subgroup analyses on the basis of intervention duration and study location also revealed no significant reductions in any group, while the level of heterogeneity remained high. Detailed findings from the subgroup analyses are provided in

Table S2.

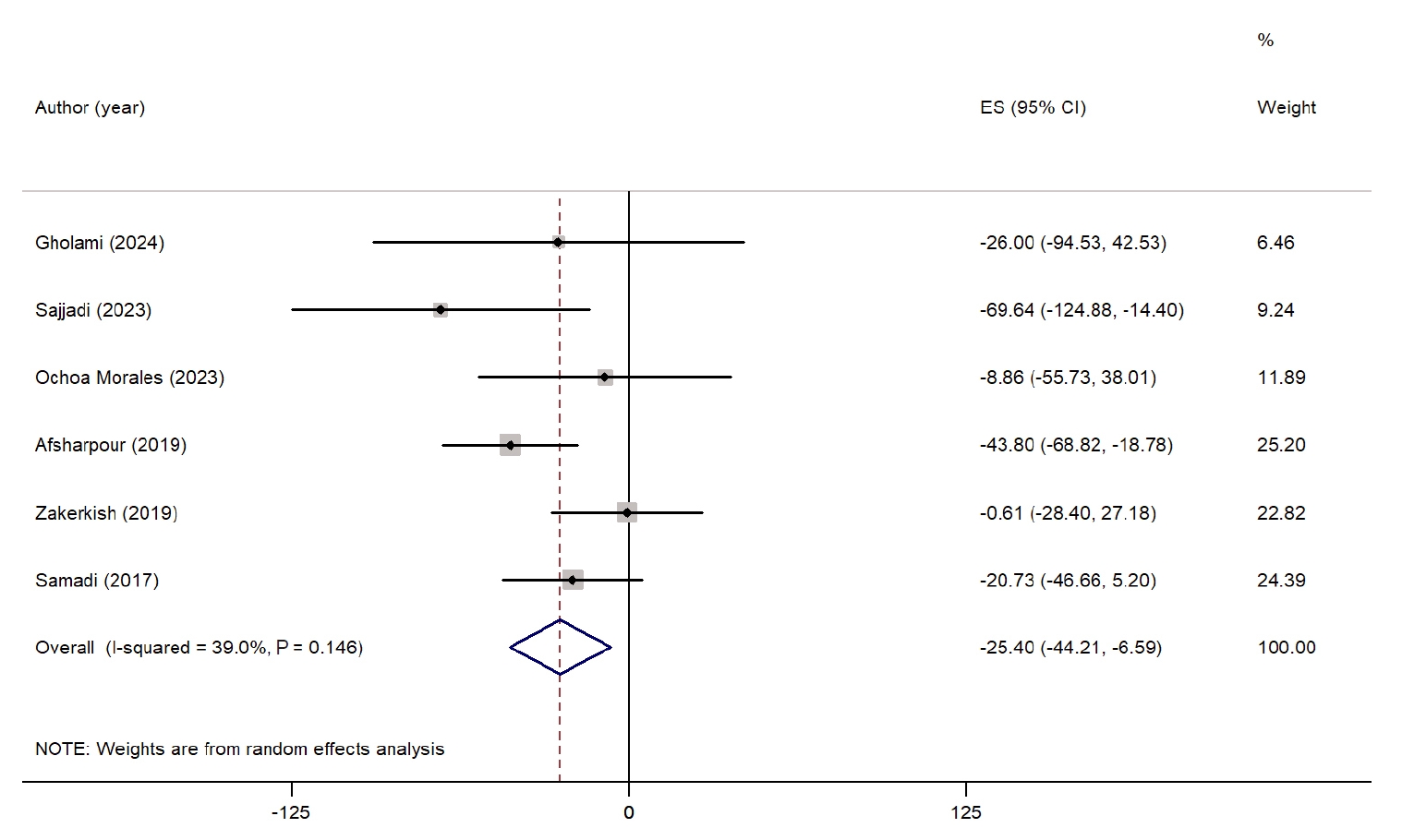

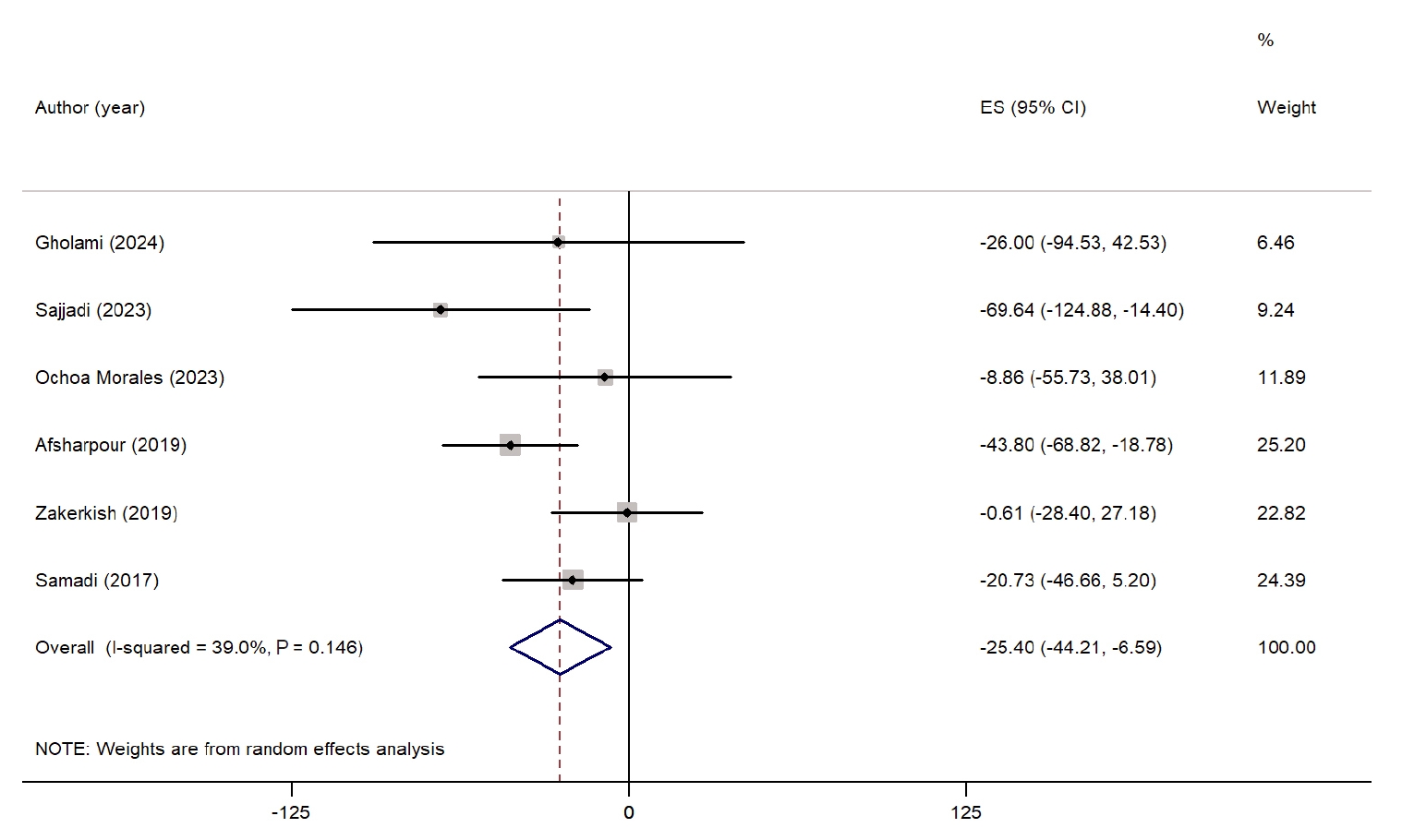

The effect of propolis supplementation on TG is presented as a forest plot in

Fig. 3. Six studies assessed the impact of propolis on TG levels [

24,

28,

30-

32,

34]. The overall results indicated that propolis supplementation significantly reduced TG levels (WMD, −25.40 mg/dL; 95% CI, −44.21 to −6.59; P=0.008). Heterogeneity among the studies was low and not statistically significant (I

2=39.0%, P=0.14). However, a sensitivity analysis demonstrated that excluding the study conducted by Afsharpour et al. [

24] resulted in a nonsignificant effect (WMD, −18.29 mg/dL; 95% CI, −37.76 to 1.16). Subgroup analysis could not be performed due to insufficient data.

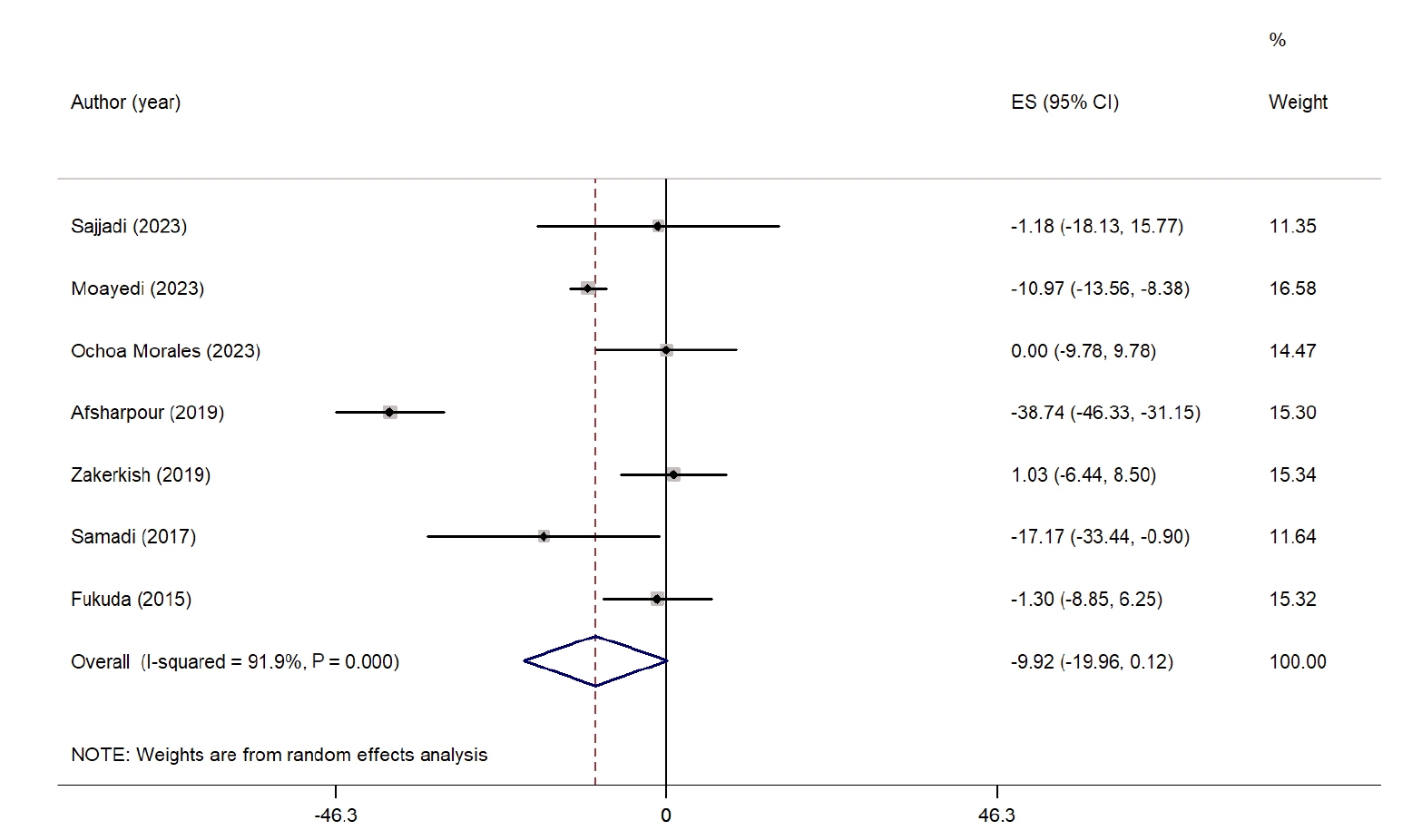

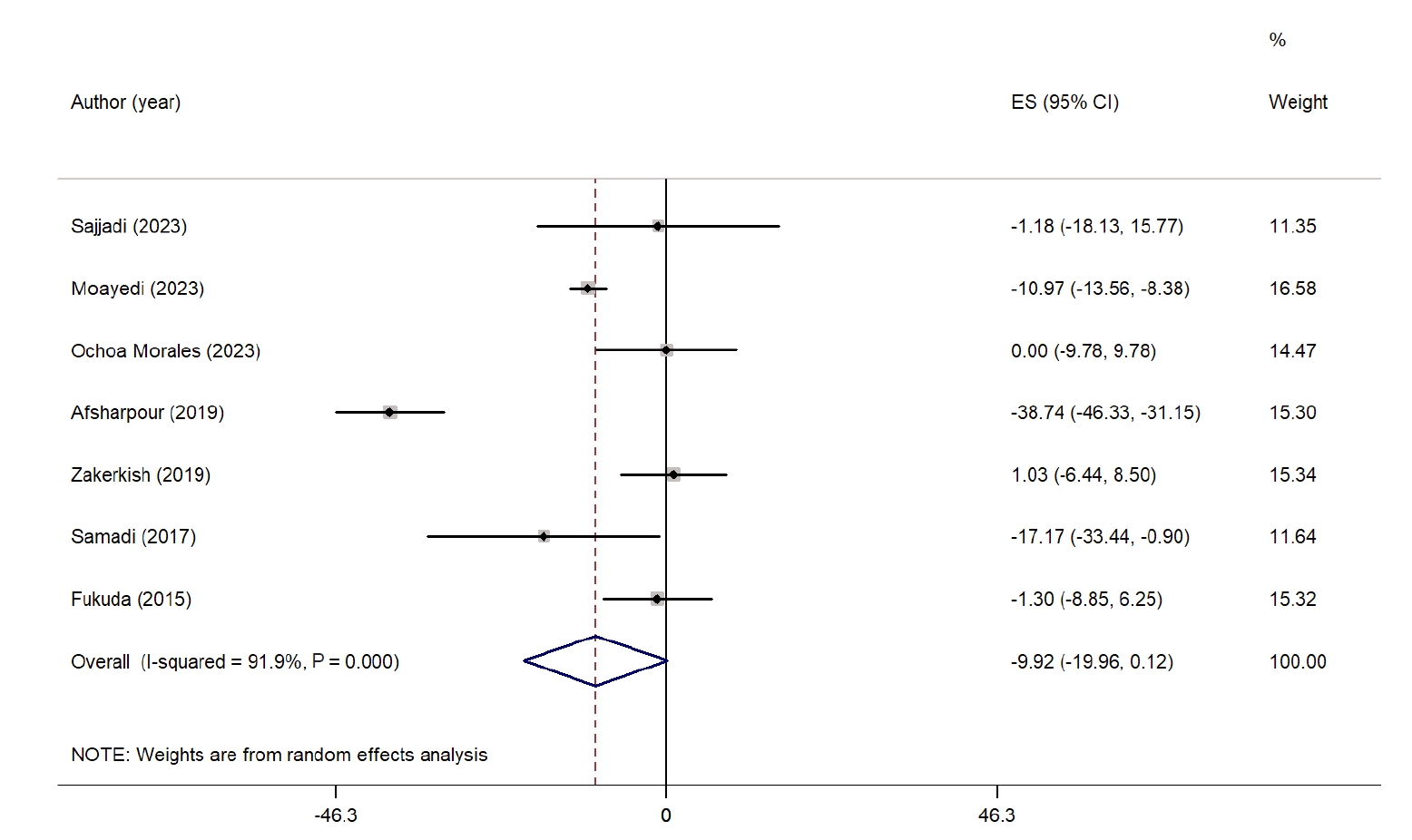

Fig. 4 summarizes the impact of propolis on LDL-C levels. A meta-analysis of seven studies revealed a nonsignificant reduction in LDL-C levels in the propolis group compared with the control group (WMD, −9.92 mg/dL; 95% CI, −19.96 to 0.12; P=0.05) [

24,

26,

29-

32,

34]. However, considerable heterogeneity was noted among the studies (I

2=91.9%, P˂0.001). No significant reduction was observed when examining subgroups based on intervention duration. Nevertheless, studies conducted in West Asian countries reported a significant decrease in LDL-C levels. Heterogeneity was relatively low among studies from non-West Asian countries and those with interventions lasting longer than 8 weeks. Sensitivity analysis indicated that excluding studies by Sajjadi et al. [

31] (WMD, −11.04 mg/dL; 95% CI, −21.91 to −0.17), Ochoa-Morales et al. [

30] (WMD, −11.58 mg/dL; 95% CI, −22.85 to −0.32), and Zhao et al. [

35] (WMD, −11.87 mg/dL; 95% CI, −23.30 to −0.45) resulted in a significant reduction, suggesting that these studies had a considerable impact on the overall results. A summary of all subgroup analyses is presented in

Table S2.

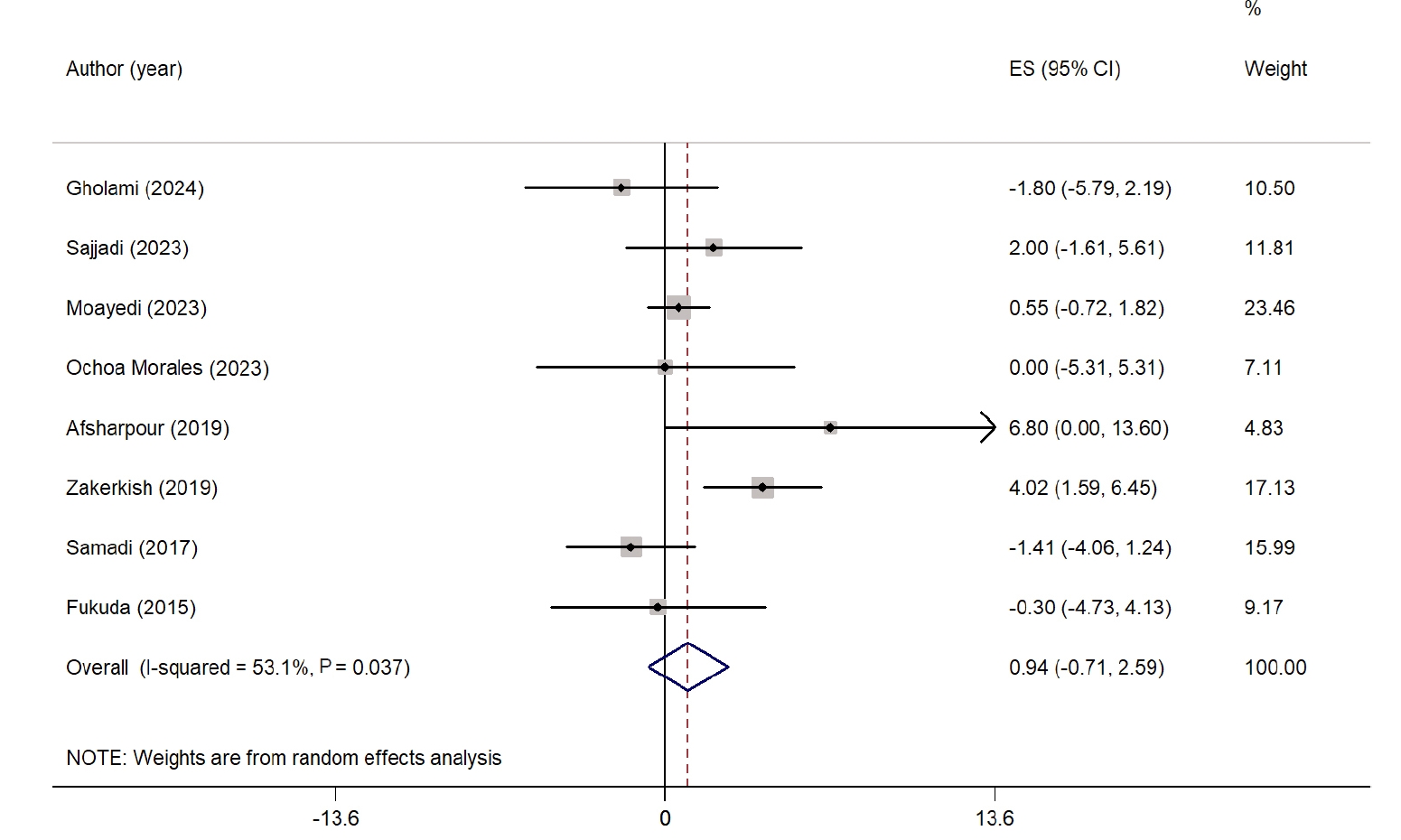

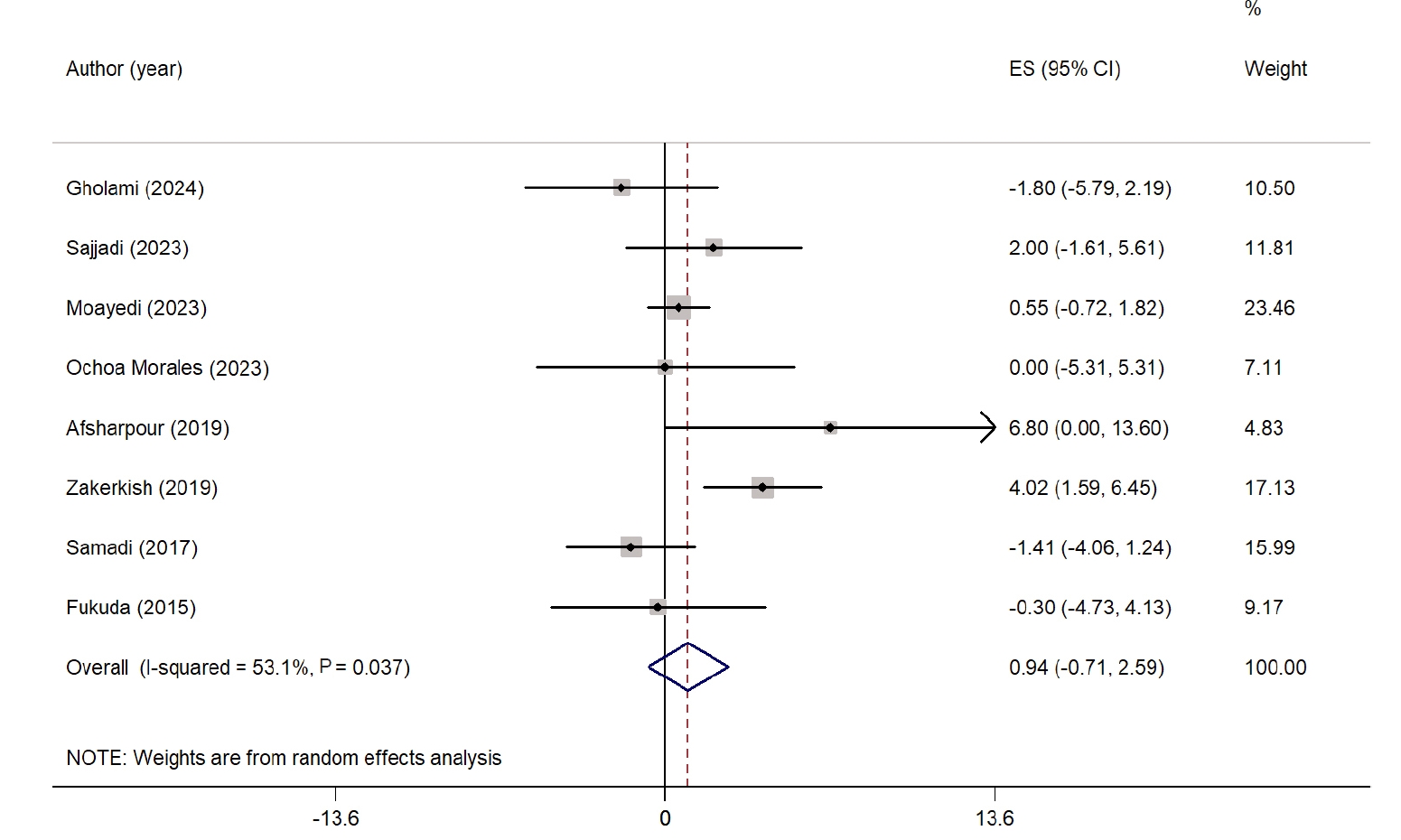

The overall effect of propolis on HDL-C is illustrated as a forest plot in

Fig. 5. Eight studies were included in the analysis of HDL-C levels [

24,

26,

28-

32,

34]. Propolis supplementation did not result in a significant improvement in HDL-C compared with the control group (WMD, 0.94 mg/dL; 95% CI, −0.71 to 2.59; P=0.26). High heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I

2=53.1%, P=0.03). However, sensitivity analysis showed that the results remained consistent and were not significantly affected by the exclusion of any individual study. No significant changes in HDL-C levels were noted in any subgroup analysis. Nevertheless, lower heterogeneity was found in studies conducted in non-West Asian countries and in studies with intervention durations ≤8 weeks. Detailed findings from the subgroup analysis are presented in

Table S2.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test. No evidence of publication bias was found in studies examining the effect of propolis supplementation on FBS (P=0.96), TC (P=0.19), TG (P=0.75), LDL-C (P=0.89), and HDL-C (P=0.76).

DISCUSSION

The results of this meta-analysis of 12 RCTs indicate that propolis supplementation significantly lowers FBS and TG levels in individuals with T2DM and MetS without significantly affecting other lipid parameters. The considerable heterogeneity among the included studies points toward notable differences in study design, participant characteristics, intervention duration, and propolis composition, necessitating the exercise of caution while interpreting the pooled results. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the outcomes for serum TG changed significantly when individual studies were excluded. Additionally, no evidence of publication bias was found for any of the outcomes.

Subgroup analyses revealed that significant reductions in FBS were observed only in studies conducted in West Asian countries and in interventions lasting more than 8 weeks. While the overall pooled effect of propolis supplementation on LDL-C was not statistically significant, a significant reduction was observed in trials conducted in West Asian countries. These findings likely reflect regional differences in dietary habits, baseline metabolic status, genetic factors, and the botanical composition of propolis, all of which may influence its bioactive profile and metabolic efficacy [

38,

39]. Longer intervention durations may provide more sustained modulation of inflammatory pathways, oxidative stress, and insulin signaling mechanisms, all of which mediate the glycemic benefits of propolis [

20,

40,

41]. Overall, these findings indicate that the metabolic effects of propolis can vary based on contextual and biological factors, highlighting the importance of considering regional characteristics and treatment duration when evaluating the efficacy of propolis.

Although the precise mechanisms underlying the metabolic effects of propolis are not fully understood, previous investigations have suggested several plausible pathways. Individuals with T2DM and MetS often experience chronic hyperglycemia, elevated TG levels, and insulin resistance, which collectively contribute to impaired glucose and lipid metabolism. These baseline metabolic disturbances create conditions in which bioactive compounds, such as those in propolis, may exert measurable effects [

16,

21,

39,

41,

42].

Propolis is rich in polyphenolic compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, and other bioactive constituents that exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

42]. These compounds may help mitigate oxidative stress and suppress inflammatory signaling, two key factors driving insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridemia in T2DM and MetS [

43,

44]. Propolis has been shown to enhance glucose uptake in peripheral tissues by activating insulin-sensitive transporters such as glucose transporter type 4. Moreover, it has been shown to improve glycolysis in liver and muscle cells and suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis, which can collectively cause FBS levels to decrease [

17,

20,

39].

Regarding lipid metabolism, propolis may influence hepatic lipid synthesis, increase fatty acid oxidation, and regulate lipoprotein metabolism, thereby lowering TG levels [

20,

45]. By attenuating systemic inflammation and the oxidative modification of lipoproteins, propolis may help improve lipid homeostasis in these high-risk populations [

21]. Clinical evidence further supports its role in downregulating inflammatory markers, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and C-reactive protein, both of which are closely linked to insulin resistance and dyslipidemia [

43]. Together, these antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulatory activities of propolis provide a mechanistic rationale for the modest improvements in FBS and TG levels observed in individuals with T2DM and MetS.

The current study has some limitations. First, due to the limited number of available studies, we were unable to perform sex-specific analyses or investigate the effects of different types of propolis and their bioactive compounds. Second, the generalizability of our findings may be limited, given that most of the included research was conducted in Iran and East Asian countries. Third, we could not fully identify the sources of heterogeneity in the case of some metabolic outcomes, necessitating caution while interpreting the results. Fourth, this review was not prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), which presents a potential methodological limitation. Nevertheless, all procedures were conducted systematically following the PRISMA guidelines.

In conclusion, propolis supplementation modestly improves FBS and TG levels in patients with T2DM and MetS. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, given the heterogeneity among the included studies and the small sample sizes. More large-scale, well-designed RCTs using standardized propolis preparations are required to verify these findings and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

NOTES

-

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: EFM, PSE. Methodology: EFM, PSE. Software: EFM, PSE. Validation: EFM, PSE. Formal analysis: EFM, PSE. Investigation: EFM, PSE, EA, LK. Data curation: EFM, PSE, EA. Writing - original draft: EFM, PSE, EA, LK. Writing - review & editing: EFM, PSE, EA, LK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflicts of interest

None.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Data of this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary materials

Fig. 1.Forest plot illustrating the effect of propolis supplementation on fasting blood sugar in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome [

24-

28,

30-

35]. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2.Forest plot illustrating the effect of propolis supplementation on total cholesterol in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome [

24,

26,

29-

32,

34]. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.Forest plot illustrating the effect of propolis supplementation on triglyceride levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome [

24,

28,

30-

32,

34]. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 4.Forest plot illustrating the effect of propolis supplementation on low-density lipoprotein in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome [

24,

26,

29-

32,

34]. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 5.Forest plot illustrating the effect of propolis supplementation on high-density lipoprotein in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome [

24,

26,

28-

32,

34]. Weights are from random-effects analysis. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1.Randomized controlled trials included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 1.

|

Study |

Country |

Intervention |

Control |

Sample size |

Sex |

Mean age (yr) |

Trial duration (wk) |

Subject |

|

Gholami et al. (2024) [28] |

Iran |

900 mg/day propolis + diet |

Placebo + diet |

84 |

Male/female |

52 |

12 |

MetS |

|

Yousefi et al. (2023) [33] |

Iran |

1,500 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

60 |

Male/female |

50 |

8 |

T2DM |

|

Sajjadi et al. (2023) [31] |

Iran |

500 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

62 |

Male/female |

54 |

12 |

MetS |

|

Moayedi et al. (2023) [29] |

Iran |

500 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

30 |

Female |

53 |

8 |

T2DM |

|

Ochoa-Morales et al. (2023) [30] |

Mexico |

600 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

24 |

Male/female |

47 |

12 |

T2DM |

|

Afsharpour et al. (2019) (Iran) [24] |

Iran |

1,500 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

60 |

Not reported |

50 |

8 |

T2DM |

|

Zakerkish et al. (2019) [34] |

Iran |

1,000 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

94 |

Male/female |

55 |

12 |

T2DM |

|

Gao et al. (2018) [27] |

China |

900 mg/day propolis |

Control |

61 |

Male/female |

59 |

18 |

T2DM |

|

Samadi et al. (2017) [32] |

Iran |

900 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

66 |

Male/female |

54 |

12 |

T2DM |

|

El-Sharkawy et al. (2016) [25] |

Egypt |

400 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

50 |

Male/female |

50 |

24 |

T2DM |

|

Zhao et al. (2016) [35] |

China |

900 mg/day propolis |

Control |

65 |

Male/female |

60 |

18 |

T2DM |

|

Fukuda et al. (2015) [26] |

Japan |

226 mg/day propolis |

Placebo |

80 |

Male/female |

69 |

8 |

T2DM |

REFERENCES

- 1. Hadi A, Arab A, Hajianfar H, et al. The effect of fenugreek seed supplementation on serum irisin levels, blood pressure, and liver and kidney function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a parallel randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Med 2020;49:102315.

- 2. Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, Webb DR, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2022;400:1803-20.

- 3. Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, et al. Idf diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;128:40-50.

- 4. Karugu CH, Agyemang C, Ilboudo PG, et al. The economic burden of type 2 diabetes on the public healthcare system in Kenya: a cost of illness study. BMC Health Serv Res 2024;24:1228.

- 5. Hidayat B, Ramadani RV, Rudijanto A, Soewondo P, Suastika K, Siu Ng JY. Direct medical cost of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in Indonesia. Value Health Reg Issues 2022;28:82-9.

- 6. Hadi A, Arab A, Khalesi S, Rafie N, Kafeshani M, Kazemi M. Effects of probiotic supplementation on anthropometric and metabolic characteristics in adults with metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Nutr 2021;40:4662-73.

- 7. Minari TP, Tacito LH, Yugar LB, et al. Nutritional strategies for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a narrative review. Nutrients 2023;15:5096.

- 8. Hamooya BM, Siame L, Muchaili L, Masenga SK, Kirabo A. Metabolic syndrome: epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic approaches. Front Nutr 2025;12:1661603.

- 9. Nilsson PM, Tuomilehto J, Ryden L. The metabolic syndrome: what is it and how should it be managed? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:33-46.

- 10. Razavi-Nematollahi L, Ismail-Beigi F. Adverse effects of glycemia-lowering medications in type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:132.

- 11. Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL, Roy C. Lifestyle change in type 2 diabetes a process model. Nurs Res 2002;51:18-25.

- 12. Bassi N, Karagodin I, Wang S, et al. Lifestyle modification for metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Med 2014;127:1242.e1-10.

- 13. Patti AM, Al-Rasadi K, Giglio RV, et al. Natural approaches in metabolic syndrome management. Arch Med Sci 2018;14:422-41.

- 14. Jin Y, Arroo RR. Application of dietary supplements in the prevention of type 2 diabetes-related cardiovascular complications. Phytochem Rev 2021;20:181-209.

- 15. Hadi A, Rafie N, Arab A. Bee products consumption and cardiovascular diseases risk factors: a systematic review of interventional studies. Int J Prop 2021;24:115-28.

- 16. Zulhendri F, Ravalia M, Kripal K, Chandrasekaran K, Fearnley J, Perera CO. Propolis in metabolic syndrome and its associated chronic diseases: a narrative review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:348.

- 17. Karimi M, Bahreini N, Pirzad S, et al. Propolis supplementation improves cardiometabolic health in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: findings from a GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2025;24:164.

- 18. Irigoiti Y, Navarro A, Yamul D, Libonatti C, Tabera A, Basualdo M. The use of propolis as a functional food ingredient: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021;115:297-306.

- 19. Etebarian A, Alhouei B, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, Esfarjani F. Propolis as a functional food and promising agent for oral health and microbiota balance: a review study. Food Sci Nutr 2024;12:5329-40.

- 20. Zhang Y, Ding S, Li W, et al. Propolis effects on blood sugar and lipid metabolism, inflammatory indicators, and oxidative stress in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2025;12:1653730.

- 21. Ahmed YB, Abdalkareem Jasim S, Mustafa YF, Husseen B, Diwan TM, Singh M. The effects of propolis supplementation on lipid profiles in adults with metabolic syndrome and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hum Nutr Metab 2024;37:200276.

- 22. Vajdi M, Bonyadian A, Pourteymour Fard Tabrizi F, et al. The effects of propolis consumption on body composition and blood pressure: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2024;101:100754.

- 23. El-Sehrawy AA, Uthirapathy S, Kumar A, et al. The effects of propolis supplementation on blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Nutr Food Sci 2025;55:233-47.

- 24. Afsharpour F, Javadi M, Hashemipour S, Koushan Y, Haghighian HK. Propolis supplementation improves glycemic and antioxidant status in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Complement Ther Med 2019;43:283-8.

- 25. El-Sharkawy HM, Anees MM, Van Dyke TE. Propolis improves periodontal status and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol 2016;87:1418-26.

- 26. Fukuda T, Fukui M, Tanaka M, et al. Effect of Brazilian green propolis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Biomed Rep 2015;3:355-60.

- 27. Gao W, Pu L, Wei J, et al. Serum antioxidant parameters are significantly increased in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after consumption of Chinese propolis: a randomized controlled trial based on fasting serum glucose level. Diabetes Ther 2018;9:101-11.

- 28. Gholami Z, Maracy MR, Paknahad Z. The effects of MIND diet and propolis supplementation on metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Heliyon 2024;10:e34493.

- 29. Moayedi F, Taghian F, Jalali Dehkordi K, Hosseini SA. Cumulative effects of exercise training and consumption of propolis on managing diabetic dyslipidemia in adult women: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial with pre-post-intervention assessments. J Physiol Sci 2023;73:17.

- 30. Ochoa-Morales PD, Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Martinez-Abundis E, Perez-Rubio KG, Patino-Laguna AD. Anti-hyperglycemic effects of propolis or metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2023;93:498-506.

- 31. Sajjadi SS, Bagherniya M, Soleimani D, Siavash M, Askari G. Effect of propolis on mood, quality of life, and metabolic profiles in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 2023;13:4452.

- 32. Samadi N, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Rahmanian M, Askarishahi M. Effects of bee propolis supplementation on glycemic control, lipid profile and insulin resistance indices in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Integr Med 2017;15:124-34.

- 33. Yousefi M, Hashemipour S, Shiri-Shahsavar MR, Koushan Y, Haghighian HK. Reducing the inflammatory interleukins with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of propolis in patients with type 2 diabetes: double-blind, randomized controlled, clinical trial. Clin Diabetol 2023;12:327-35.

- 34. Zakerkish M, Jenabi M, Zaeemzadeh N, Hemmati AA, Neisi N. The effect of Iranian propolis on glucose metabolism, lipid profile, insulin resistance, renal function and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Sci Rep 2019;9:7289.

- 35. Zhao L, Pu L, Wei J, et al. Brazilian green propolis improves antioxidant function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:498.

- 36. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. A John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2008.

- 37. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71.

- 38. Zhu L, Zhang J, Yang H, et al. Propolis polyphenols: a review on the composition and anti-obesity mechanism of different types of propolis polyphenols. Front Nutr 2023;10:1066789.

- 39. Karimian J, Hadi A, Pourmasoumi M, Najafgholizadeh A, Ghavami A. The efficacy of propolis on markers of glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res 2019;33:1616-26.

- 40. Pahlavani N, Malekahmadi M, Firouzi S, et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the effects of propolis in inflammation, oxidative stress and glycemic control in chronic diseases. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2020;17:65.

- 41. Wong CN, Lee SK, Liew KB, Chew YL, Chua AL. Mechanistic insights into propolis in targeting type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Planta Med 2025;91:496-512.

- 42. Zullkiflee N, Taha H, Usman A. Propolis: its role and efficacy in human health and diseases. Molecules 2022;27:6120.

- 43. Bahari H, Shahraki Jazinaki M, Aliakbarian M, et al. Propolis supplementation on inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr 2025;12:1542184.

- 44. Masenga SK, Kabwe LS, Chakulya M, Kirabo A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:7898.

- 45. Khoshandam A, Hedayatian A, Mollazadeh A, Razavi BM, Hosseinzadeh H. Propolis and its constituents against cardiovascular risk factors including obesity, hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and dyslipidemia: a comprehensive review. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2023;26:853-71.