ABSTRACT

Vaccinium meridionale Swartz (commonly known as agraz or Andean blueberry is a wild fruit native to Colombia and rich in anthocyanins. In this systematic review, we evaluated the effects of agraz supplementation on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in individuals with metabolic syndrome (MetS). A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, and Google Scholar for articles published up to March 2024, without restrictions on language, publication date, or geographical region. Among the 2,616 records identified initially through the database searches, 6 studies were included in this review. The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. Six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 252 participants were analyzed. The intervention durations ranged from 21 days to 4 weeks, and the agraz supplementation doses were between 200 and 250 mL per day. Agraz supplementation significantly reduced urinary and serum levels of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). However, among 3 studies examining high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels, only 1 reported a statistically significant decrease in its levels. No significant effects were observed for other inflammatory or oxidative stress biomarkers. Agraz supplementation notable reduced urinary and serum 8-OHdG levels, suggesting potential antioxidant effects; however, its effect on hs-CRP levels remains inconclusive. No significant changes were observed in the levels of the other biomarkers. Further RCTs with larger doses and longer durations are necessary to confirm these findings and to clarify the therapeutic potential of agraz in MetS.

-

Trial Registration

-

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome; Vaccinium; Oxidative stress; Inflammation; Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as a cluster of interrelated metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance, central obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) concentrations, and hypertension. It is also associated with the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (CVD), one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide [

1].

MetS is also linked to chronic inflammation resulting from increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [

2]. Additionally, increased systemic oxidative stress is commonly observed in patients with MetS. This oxidative imbalance is associated with systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, as well as oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA [

3]. The impacts of oxidative stress can be assessed using biomarkers such as 8-isoprostane, a product of lipid peroxidation in biological membranes, and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), which is an indicator of oxidative damage to DNA [

4].

Currently, lifestyle changes such as increased physical activity, dietary modifications, and high consumption of fruits and vegetables are considered the first-line treatment for MetS [

5]. Several studies have reported that polyphenolic compounds, such as anthocyanins derived from fruits and vegetables, exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [

6].

Vaccinium meridionale Swartz (commonly known as agraz or Andean blueberry) is a wild berry native to Colombia and a rich natural source of anthocyanins [

7]. Recently, there has been a growing interest in examining the effects of agraz on human health owing to its high phenolic content and strong antioxidant capacity [

8]. One clinical trial reported that agraz supplementation was associated with reductions in several cardiovascular risk factors, including body mass index, blood pressure, and waist circumference [

9]. Moreover, Espinosa-Moncada et al. [

8] reported that 4 weeks of agraz supplementation in women with MetS reduced oxidative DNA damage and increased total antioxidant capacity (TAC). In addition, another study found no significant improvements in the levels of HDL or inflammatory markers in women with MetS after agraz supplementation [

10].

Considering the evidence on the effects of agraz on inflammation and oxidative stress status as important factors in CVD and MetS has not been substantiated, the current systematic review sought to provide an accurate evaluation of the effects of agraz on inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

11]. The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (

http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) under the registration number

CRD42022369292.

A comprehensive search was conducted across 4 electronic databases, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to identify relevant studies published up to March 2024. The following search query was used: (Vaccinium OR agraz OR “Vaccinium meridionale Swartz” OR Andean blueberry* OR Colombian berry* OR “Vaccinium meridionale”) AND (intervention OR Intervention* OR trial OR randomized OR randomised OR random OR randomly[tiab] OR placebo OR assignment OR RCT OR “Clinical Trials as Topic” OR cross-over OR parallel) NOT (mouse OR mice OR rats OR in-vitro OR “in vitro”).

The search was not restricted by language, publication date, or other filters. Two researchers (A.G. and H.B.) screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved records and excluded irrelevant studies, and discrepancies were resolved by consultation with additional reviewers. Furthermore, the reference lists of the included articles were manually reviewed to identify additional eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the review based on the following criteria: 1) evaluation of the effects of agraz supplementation in human participants, 2) participants aged 18 years or older, 3) assessment of the impact of agraz supplementation on the levels of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers, and 4) original randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) duplicate reports of the same study; 2) observational, nonrandomized, or noncontrolled trials; review articles; in vitro studies, letters to the editor; and animal studies; 3) studies evaluating only the acute effects of agraz supplementation; and 4) studies that did not report the biomarkers targeted in this review.

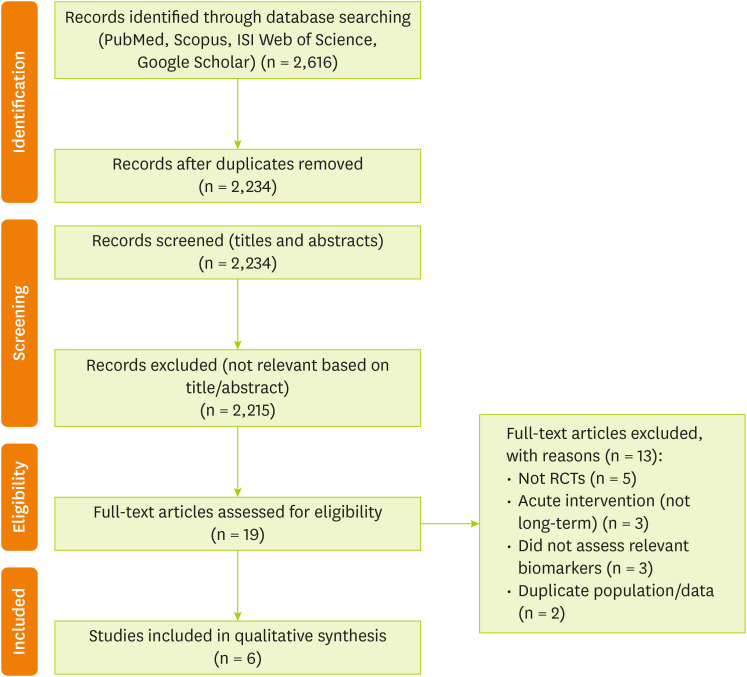

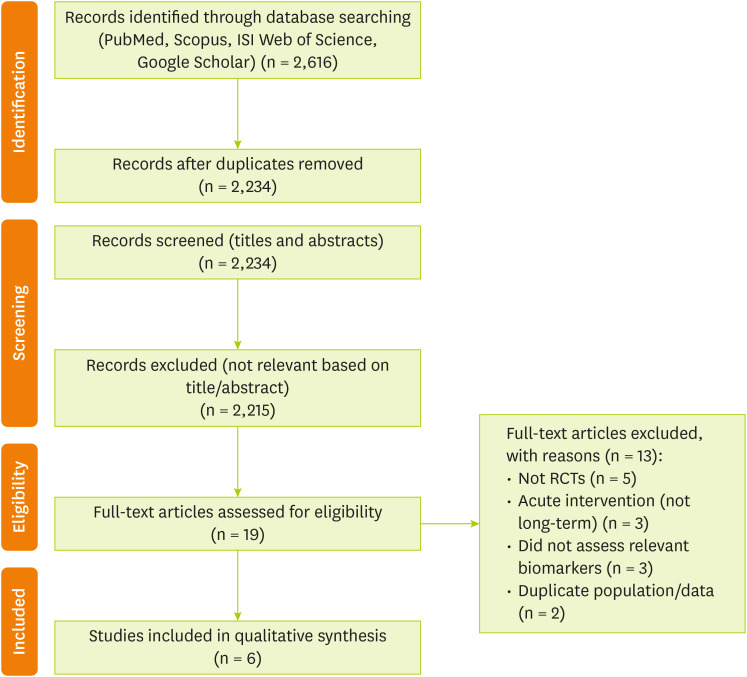

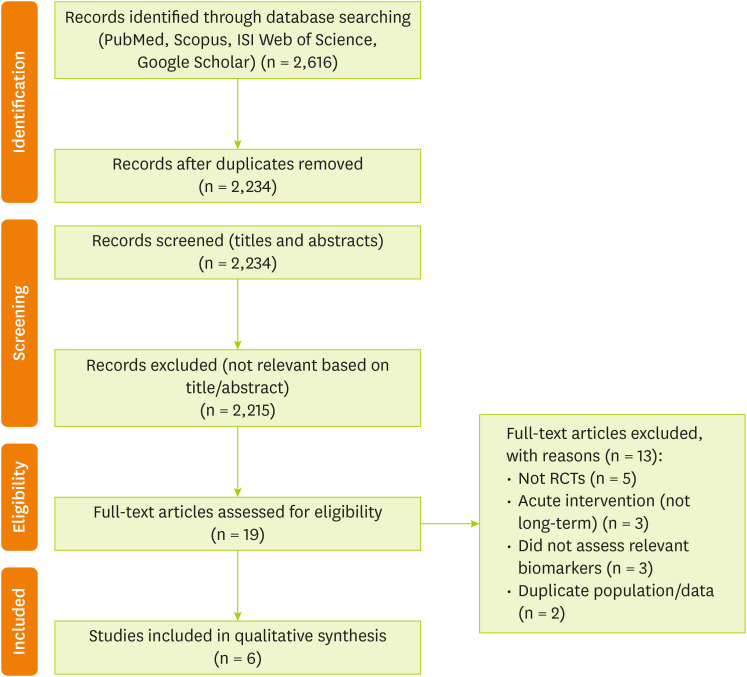

After the screening of 2,616 records identified through the database searches, 6 studies were included in the final systematic review (

Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each included study: first author, publication year, study location, trial design, participant age and gender, sample size, duration of follow-up, participant characteristics, and the type and administered dose of both agraz and placebo. Data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators (E.N.E. and Z.K.), and the process was subsequently verified by other members of the research team. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through team discussion and consensus.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for the systematic review of intervention studies [

12] was used to evaluate the potential risk of bias in the included studies. The following domains were assessed: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel, outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Two independent reviewers (A.G. and E.N.E.) conducted a risk of bias assessment for each eligible study, and the results were verified by a third reviewer. Each domain was rated as low risk, high risk, or unclear risk of bias. The overall study quality was stratified as weak, fair, or good based on the number of domains rated as low risk: < 3, 3, or ≥ 4, respectively.

RESULTS

Study selection

A total of 2,616 records were identified through the database searches. After removing 382 duplicates, 2,234 records remained for title and abstract screening, following which 19 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Following a thorough evaluation of the full texts, 13 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 6 clinical trials were included in this systematic review. These articles studied the effects of

V. meridionale Swartz (agraz) supplementation on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in patients with MetS [

8,

10,

13,

14,

15,

16].

The characteristics and main findings of the included trials are summarized in

Table 1.

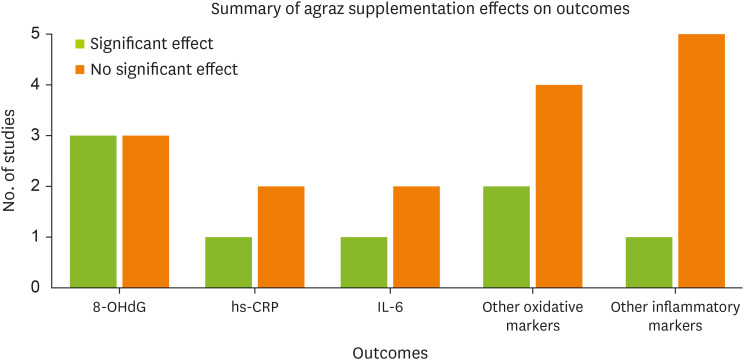

Figure 2 provides a summary of the distribution of the key study outcomes, illustrating the number of studies reporting statistically significant versus nonsignificant effects of agraz supplementation on the levels of 8-OHdG, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and other oxidative and inflammatory biomarkers. All the included trials were conducted in Colombia [

8,

10,

13,

14,

15,

16], with a total of 278 participants enrolled across 6 parallel-design studies. The intervention durations ranged from 21 days to 4 weeks, and the agraz dosages varied from 200 mL per day to 250 mL per day. Four studies were conducted exclusively on women [

8,

10,

15,

16], while two studies included both men and women [

13,

14]. The trials assessed a wide range of antioxidant capacity and oxidative stress markers, including total phenols, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, 8-OHdG (serum and urinary), F2-isoprostanes, 8-isoprostanes, paraoxonase 1 (PON1) lactonase activity, myeloperoxidase (MPO), advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), ferric reducing ability of plasma, oxygen radical absorbance capacity, oxidized low-density lipoprotein, and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS). The levels of enzymatic antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) were also quantified. The inflammatory biomarkers evaluated included CRP, hs-CRP, serum adiponectin, leptin, resistin, IL-1β, TNF-α, adiponectin, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and MCP-1.

Table 1Detailed characteristics of eligible randomized controlled trials on agraz supplementation

Table 1

|

Authors |

Year |

Study design |

No. of participants (age range) |

Health status |

Agraz group description |

Intervention (duration and dosage) |

Control group |

Outcome measures |

|

Espinosa-Moncada et al. [8] |

2018 |

RCT |

40 women (28–66 years) |

MetS |

Nectar (reconstituted from freeze-dried agraz) |

4 weeks; daily dose calculated based on the total phenol content in 200 g fresh fruit in 200 mL water (1,027.97 ± 41.99 mg gallic acid equivalents/L of agraz beverage) |

Placebo |

Antioxidant capacity and oxidation markers: Total phenols (↔), DPPH (↑), TBARS (↔), 8-OHdG (↓), F2-Isoprostanes (↔) |

|

Inflammatory markers: hs-CRP, serum adiponectin, leptin, resistin (↔) |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [10] |

2018 |

RCT |

40 women (25–60 years) |

MetS |

Freeze-dried agraz |

4 weeks; daily dose |

Placebo |

PON1 lactonase, MPO, AOPP (↔) |

|

TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, NF-κB (↔) |

|

Galvis-Pérez et al. [13] |

2020 |

RCT |

26 men, 26 women (NR) |

MetS |

Agraz nectar |

4 weeks; daily dose (200 mL nectar) |

Placebo |

FRAP, TBARS, OxLDL (↔) |

|

hs-CRP, NF-κB (↔) |

|

Galvis Pérez [14] |

2018 |

RCT |

40 women, 26 men (46.6 ± 10.4 years) |

MetS |

Freeze-dried agraz nectar |

4 weeks; daily dose (200 mL nectar) |

Placebo |

Total phenols (↔), DPPH, ORAC, ABTS, FRAP (↔) |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [15] |

2021 |

RCT |

40 women (47.2 ± 9.4 years) |

MetS |

Agraz beverage |

4 weeks; daily dose (200 mL) |

Placebo |

SOD, CAT, GPx, ABTS, FRAP, ORAC, F2-Isoprostanes (↔) |

|

8-OHdG (↓) |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [16] |

2020 |

RCT |

40 women (25–60 years) |

MetS |

Freeze-dried agraz powder |

4 weeks; daily dose (200 mL containing 1,027.97 ± 41.99 mg gallic acid) |

Placebo |

ORAC, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, CAT, GPx, PON1 lactonase, AOPP, 8-isoprostane, MPO (↔) |

|

Urinary 8-OHdG (↓) |

|

Adiponectin (↔) |

|

hs-CRP (↓) |

Figure 2

Summary of the effects of agraz supplementation on oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers in the included randomized controlled trials. This figure presents the number of studies reporting significant versus nonsignificant effects across four key outcome categories.

8-OHdG, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL, interleukin.

Studies on oxidation markers and antioxidant capacity

The six studies reviewed herein examined the effects of agraz supplementation on the levels of oxidative stress markers and antioxidant capacity. In one study, 4 weeks of agraz supplementation led to an increase in DPPH activity in the intervention group compared to that in the control group [

8]. Three studies reported a reduction in 8-OHdG levels following agraz supplementation compared to those in the control group [

8,

15,

16]. These studies administered 200 mL of an agraz beverage to the participants daily for 4 weeks. In the studies by Agudelo et al. [

17] and Gallego Peláez et al. [

18], the supplementation group showed improved antioxidant capacity. Specifically, Agudelo et al. [

17] administered 250 mL of agraz juice daily for 14 days, while Gallego Peláez et al. [

18] used 35 g of osmo-dehydrated agraz for 21 days. Agudelo et al. [

17] reported a reduction in 8-isoprostanes and total polyphenol levels in the supplementation group following the intervention. The levels of other oxidative stress markers assessed across studies were not statistically significantly different between the supplementation and control groups.

The effects of agraz supplementation on inflammatory markers, including CRP, hs-CRP, serum adiponectin, leptin, resistin, IL-1, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, were assessed in the included studies. In the study by Agudelo et al. [

17], which included 19 women and men aged 18–60 years, the IL-6 levels were reduced in the supplementation group compared to that in the control group after a 14-day intervention with 250 mL of agraz juice per day. Gallego Peláez et al. [

18] reported a decrease in adiponectin levels in the supplementation group after supplementation of 35 g of osmo-dehydrated berry for 21 days. Moreover, after intervention with 200 ml of agraz juice (containing 1,027.97 ± 41.99 mg gallic acid) for 4 weeks, Marín-Echeverri et al. [

15,

16] reported that hs-CRP levels significantly decreased in the supplementation group. Other inflammatory markers did not show significant changes between the supplementation groups and control groups after intervention in any of the included studies.

Details of the quality assessment of the studies included in this systematic review based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s tools [

12] are presented in

Table 2. As shown in the table, 3 of the 6 studies described the method used for random sequence generation [

8,

15,

16], while only 2 studies provided details on allocation concealment [

8,

13]. All 6 studies reported blinding of participants and personnel [

8,

10,

13,

14,

15,

16]; however, blinding of outcome assessment was unclear in all cases. Selective reporting, attrition bias, or incomplete outcome data were identified in all but one study [

14].

Table 2Risk of bias assessment and study quality based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool

Table 2

|

Study |

Year |

Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding (participants and personnel) |

Blinding (outcome assessment) |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective reporting |

General quality |

|

Espinosa-Moncada et al. [8] |

2018 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Galvis Pérez [14] |

2018 |

? |

? |

+ |

? |

? |

? |

? |

|

Galvis-Pérez et al. [13] |

2020 |

? |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [10] |

2018 |

? |

? |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [16] |

2020 |

+ |

? |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Marín-Echeverri et al. [15] |

2021 |

+ |

? |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

DISCUSSION

This systematic review assessed the effects of agraz supplementation on oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in patients with MetS. These findings suggest that agraz supplementation significantly reduces urinary and serum levels of 8-OHdG, a key biomarker of DNA oxidative damage. However, its effects on other biomarkers, such as hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, and enzymatic antioxidants (e.g., SOD, CAT, and GPx), were either inconsistent or nonsignificant across studies.

Agraz supplementation did not show significant effects on TNF-α, IL-1β, hs-CRP, NF-κB, MPO, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), AOPP, F2-isoprostanes, and 8-isoprostane levels. While reductions in 8-OHdG levels were consistently observed, effects on most other biomarkers were variable and inconclusive; therefore, we exercised caution in this review.

The studies included in this review had inconsistent results regarding the effects of agraz supplementation on inflammatory markers, highlighting the need for further research in this field. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and hs-CRP significantly reduced with a daily dose intervention of agraz in a study conducted by Espinosa-Moncada et al. [

8]. However, in four other studies that involved participants with MetS and similar intervention doses, the levels of inflammatory markers such as TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, and NF-κB showed no significant changes [

8,

13,

16], except for a reduction in hs-CRP levels as reported by Marín-Echeverri et al. [

16], which was observed only in overweight women. The underlying mechanism for this effect is likely due to the suppression of NF-κB translocation and the activation of the liver X receptor alpha pathway, which induces trans-repression of NF-κB through the polyphenolic compounds present in agraz [

19,

20]. In individuals with obesity, the greater inflammatory burden may require longer treatment durations and lifestyle changes to yield similar results [

16]. Nevertheless, bioactive compounds in agraz, such as gallic acid and chlorogenic acid, have been shown to inhibit NF-κB translocation and suppress the expression of proinflammatory genes, including inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

18]. While TNF-α and IL-1β expression typically increases in advanced stages of cancer, the study by Agudelo et al. [

17] involved healthy participants, which may explain the absence of significant effects. Furthermore, the interaction between female sex hormones and agraz supplementation may enhance nitric oxide production, potentially contributing to the observed reductions in inflammatory marker levels among women [

13].

The included studies showed that TAC and SOD, CAT, and GPx activities did not exhibit significant changes following agraz supplementation. While most studies using similar dosages reported no significant increase in TAC, Espinosa-Moncada et al. [

8] reported a consistent increase in TAC with agraz supplementation. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of agraz are likely attributable to its high polyphenolic compound content, particularly anthocyanins, gallic acid, and chlorogenic acid [

18]. Notably, individuals with MetS tend to exhibit higher levels of oxidative stress and lower bioavailability of anthocyanins, the primary polyphenols in agraz [

21]. Therefore, a more extended intervention period or a higher concentration of anthocyanins in agraz supplements may enhance their effectiveness in mitigating oxidative stress. Gallic acid, with high bioavailability in agraz, is a compound other than anthocyanins that has been shown to increase plasma antioxidant capacity and prevent lipid peroxidation. Increases in plasma antioxidant capacity have been observed in some studies using the DPPH and ABTS methods [

17,

18].

Moreover, anthocyanins may increase energy expenditure by upregulating mitochondrial function in brown adipose tissue [

22,

23]. An inverse relationship between TAC and central obesity has also been reported [

20]. In line with this, Marín-Echeverri et al. [

15] reported that an increase in serum TAC (as determined using ABTS) was associated with a reduction in waist circumference among women. Similarly, Espinosa-Moncada et al. [

8] suggested that agraz supplementation may help decrease the relationship between high triglycerides and elevated markers of lipid peroxidation. Gender-based analysis also revealed a minimal increase in antioxidant capacity among women, which may be due to hormonal factors [

13].

Agraz supplementation exhibited no significant effect on SOD, CAT, or GPx activities. Marín-Echeverri et al. [

15,

16] used comparable intervention dosages and reported no considerable changes in these enzyme activities as well. Although some studies have indicated that anthocyanins may increase antioxidant enzyme activity, thereby decreasing reactive oxygen species levels [

24,

25], the precise underlying mechanisms remain unclear. However, several authors have reported that polyphenols and their metabolites induce the activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, a key transcription factor involved in regulating antioxidant response [

26]. The protective effects of SOD and GPx are well known: SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) [

23,

27], while GPx reduces H

2O

2 to H

2O by converting reduced glutathione (GSH) into GSH oxidized form or glutathione disulfide [

28]. Additionally, Marín-Echeverri et al. [

15] reported that changes in CAT activity were associated with a reduction in lipid peroxidation markers, such as F2-isoprostane, in obese women after agraz supplementation. Similarly, changes in SOD activity have been associated with fewer DNA oxidative markers, such as 8-OHdG, in overweight women. Moreover, a decrease in hs-CRP levels was correlated with increased PON1 activity, suggesting that agraz may exert anti-inflammatory effects through PON1-mediated inhibition of NF-κB [

8,

16]. An increase in SOD and CAT activities is negatively correlated with changes in oxidative stress and inflammatory markers such as 8-OHdG and F2-isoprostane in women [

15,

16].

Our findings revealed that the effect of agraz supplementation (with equal doses) on oxidative stress was comparable primarily to its impact on TAC, except for 8-OHdG [

8,

15,

16]. This exception may be attributed to a significant increase in serum antioxidant capacity as measured using the DPPH method [

8]. A significant reduction in 8-OHdG levels was observed after agraz supplementation in obese women and women with MetS. The observed reduction in 8-OHdG in these populations highlights the potential gender-specific effects of agraz, possibly influenced by hormonal variations and baseline oxidative stress levels. Furthermore, this reduction was associated with increased SOD activity in these women [

16]. However, other studies involving similar populations reported significant reductions in oxidative stress markers, including OxLDL, malondialdehyde (MDA), hydroxynonenal, and AOPP, after consuming other types of berries [

12,

29,

30]. There were no significant changes in MPO, MDA, OxLDL, AOPP, F2-isoprostanes, and 8-isoprostane in the agraz groups (equal dosages) across the included studies. However, changes in MPO levels were positively associated with inflammatory markers. MPO acts on HDL dysfunction through oxidative modifications, unlike PON1, and it is the primary producer of AOPP, a key marker of protein oxidation implicated in the progression of atherosclerotic plaque formation. A significant negative correlation was observed between AOPP and HDL-cholesterol after agraz supplementation. This effect may be attributed to the inhibitory effect of certain polyphenols on MPO, potentially through direct molecular binding [

8]. In a study by Galvis-Pérez et al. [

13], a reduction in OxLDL levels was observed in men compared to that in women, which coincided with an increase in their antioxidant capacity. Moreover, Agudelo et al. [

17] reported a decrease in 8-isoprostane levels after agraz intervention.

This review has several methodological strengths. It adheres to the PRISMA guidelines and was registered in the PROSPERO database. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases with no restrictions on language, publication date, or geographic region. Moreover, the inclusion of only RCTs enhanced the validity and reliability of the findings.

However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The number of included RCTs was small, with most studies conducted in Colombia by similar research teams, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Additional limitations include small sample sizes, short intervention durations, lack of consistency in the biomarkers assessed, and a predominance of female participants. These factors constrain the ability to draw definitive conclusions and highlight the need for larger, more diverse, and methodological clinical trials in future research.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this systematic review indicate that agraz supplementation reduces urinary and serum levels of 8-OHdG, a biomarker of DNA oxidative damage. However, evidence regarding its effects on hs-CRP remains controversial. No significant changes were observed in the other inflammatory or oxidative stress biomarkers. To better understand the potential health benefits of agraz supplementation, additional RCTs with higher doses and longer intervention periods are needed.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing does not apply to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

-

Author Contributions:

Data curation: Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Investigation: Moghaddas Mashhour Z, Barghchi H, Gheflati A, Khorasnchi Z, Bahri Binabaj N, Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Methodology: Barghchi H, Gheflati A, Bahri Binabaj N, Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Project administration: Gheflati A, Nattagh-Eshtivani E

Resources: Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Supervision: Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Visualization: Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

Writing - original draft: Moghaddas Mashhour Z, Mansouri AH, Dehnavi Z, Sahebanmaleki M, Moshari J.

Writing - review & editing: Barghchi H, Nattagh-Eshtivani E.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fahed G, Aoun L, Bou Zerdan M, Allam S, Bou Zerdan M, et al. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:786.

- 2. Silveira Rossi JL, Barbalho SM, Reverete de Araujo R, Bechara MD, Sloan KP, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: going beyond traditional risk factors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2022;38:e3502.

- 3. Bonomini F, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis 2015;6:109-120.

- 4. Kurti SP, Emerson SR, Rosenkranz SK, Teeman CS, Emerson EM, et al. Post-prandial systemic 8-isoprostane increases after consumption of moderate and high-fat meals in insufficiently active males. Nutr Res 2017;39:61-68.

- 5. Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome update. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2016;26:364-373.

- 6. Amiot MJ, Riva C, Vinet A. Effects of dietary polyphenols on metabolic syndrome features in humans: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2016;17:573-586.

- 7. Garzón G, Narváez C, Riedl K, Schwartz SJ. Chemical composition, anthocyanins, non-anthocyanin phenolics and antioxidant activity of wild bilberry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) from Colombia. Food Chem 2010;122:980-986.

- 8. Espinosa-Moncada J, Marín-Echeverri C, Galvis-Pérez Y, Ciro-Gómez G, Aristizábal JC, et al. Evaluation of agraz consumption on adipocytokines, inflammation, and oxidative stress markers in women with metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2018;10:1639.

- 9. Torres D, Reyes-Dieck C, Gallego E, Gómez-García A, Posada G, et al. Impact of osmodehydrated Andean berry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) on overweight adults. Vitae 2018;25:141-147.

- 10. Marín-Echeverri C, Blesso CN, Fernández ML, Galvis-Pérez Y, Ciro-Gómez G, et al. Effect of agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) on high-density lipoprotein function and inflammation in women with metabolic syndrome. Antioxidants 2018;7:185.

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Reprint--preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther 2009;89:873-880.

- 12. Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- 13. Galvis-Pérez Y, Marín-Echeverri C, Franco Escobar CP, Aristizábal JC, Fernández ML, et al. Comparative evaluation of the effects of consumption of Colombian agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) on insulin resistance, antioxidant capacity, and markers of oxidation and inflammation, between men and women with metabolic syndrome. Biores Open Access 2020;9:247-254.

- 14. Galvis Pérez Y. Evaluación comparativa de los efectos del consumo del agraz colombiano (Vaccinium meriodionale Swarz) en la resistencia a la insulina, capacidad antioxidante y marcadores de oxidación e inflamación, entre hombres y mujeres con síndrome metabólico [master’s thesis]. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia; 2018.

- 15. Marín-Echeverri C, Piedrahita-Blandón M, Galvis-Pérez Y, Blesso CN, Fernández ML, et al. Improvements in antioxidant status after agraz consumption was associated to reductions in cardiovascular risk factors in women with metabolic syndrome. CYTA J Food 2021;19:238-246.

- 16. Marín-Echeverri C, Piedrahita-Blandón M, Galvis-Pérez Y, Nuñez-Rangel V, Blesso CN, et al. Differential effects of Agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) consumption in overweight and obese women with metabolic syndrome. J Food Nutr Res 2020;8:399-409.

- 17. Agudelo CD, Ceballos N, Gómez-García A, Maldonado-Celis ME, et al. Andean berry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) juice improves plasma antioxidant capacity and IL-6 levels in healthy people with dietary risk factors for colorectal cancer. J Berry Res 2018;8:251-261.

- 18. Gallego Peláez E, Maldonado Celis ME, Posada Jhonson LG, Gómez García AC, Torres Camargo D. Consumption of osmo-dehydrated Andean berry (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) decreases levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers of overweight and obese adults. Vitae 2021;28:343810.

- 19. Karlsen A, Paur I, Bøhn SK, Sakhi AK, Borge GI, et al. Bilberry juice modulates plasma concentration of NF-kappaB related inflammatory markers in subjects at increased risk of CVD. Eur J Nutr 2010;49:345-355.

- 20. Du C, Shi Y, Ren Y, Wu H, Yao F, et al. Anthocyanins inhibit high-glucose-induced cholesterol accumulation and inflammation by activating LXRα pathway in HK-2 cells. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:5099-5113.

- 21. Zhong S, Sandhu A, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman B. Characterization of wild blueberry polyphenols bioavailability and kinetic profile in plasma over 24-h period in human subjects. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017;61:1700405.

- 22. Matsukawa T, Inaguma T, Han J, Villareal MO, Isoda H. Cyanidin-3-glucoside derived from black soybeans ameliorate type 2 diabetes through the induction of differentiation of preadipocytes into smaller and insulin-sensitive adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem 2015;26:860-867.

- 23. Matsukawa T, Villareal MO, Motojima H, Isoda H. Increasing cAMP levels of preadipocytes by cyanidin-3-glucoside treatment induces the formation of beige phenotypes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem 2017;40:77-85.

- 24. Huang W, Yan Z, Li D, Ma Y, Zhou J, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of blueberry anthocyanins on high glucose-induced human retinal capillary endothelial cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018;2018:1862462.

- 25. Huang WY, Wu H, Li DJ, Song JF, Xiao YD, et al. Protective effects of blueberry anthocyanins against H2O2-induced oxidative injuries in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Agric Food Chem 2018;66:1638-1648.

- 26. Hwang YP, Choi JH, Choi JM, Chung YC, Jeong HG. Protective mechanisms of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol 2011;49:2081-2089.

- 27. Nattagh-Eshtivani E, Barghchi H, Pahlavani N, Barati M, Amiri Y, et al. Biological and pharmacological effects and nutritional impact of phytosterols: a comprehensive review. Phytother Res 2022;36:299-322.

- 28. Mills GC. Hemoglobin catabolism. I. Glutathione peroxidase, an erythrocyte enzyme which protects hemoglobin from oxidative breakdown. J Biol Chem 1957;229:189-197.

- 29. Wang X, Yang Z, Xue B, Shi H. Activation of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Endocrinology 2011;152:836-846.

- 30. Farah A, Monteiro M, Donangelo CM, Lafay S. Chlorogenic acids from green coffee extract are highly bioavailable in humans. J Nutr 2008;138:2309-2315.

, Alireza Gheflati4

, Alireza Gheflati4 , Amir Hossein Mansouri5, Zahra Dehnavi2

, Amir Hossein Mansouri5, Zahra Dehnavi2 , Zahra Khorasnchi2

, Zahra Khorasnchi2 , Narjes Bahri Binabaj6

, Narjes Bahri Binabaj6 , Mohsen Sahebanmaleki7

, Mohsen Sahebanmaleki7 , Jalil Moshari8

, Jalil Moshari8 , Elyas Nattagh-Eshtivani1

, Elyas Nattagh-Eshtivani1