ABSTRACT

Neurocritically ill patients often encounter challenges in maintaining adequate enteral nutrition (EN) owing to metabolic disturbances associated with increased intracranial pressure, trauma, seizures, and targeted temperature management. This case report highlights the critical role of the nutrition support team (NST) in overcoming these barriers and optimizing EN delivery in a patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI). A 59-year-old man was admitted to the neuro-intensive care unit following TBI. EN was initiated early in accordance with clinical guidelines. By the time of transfer to the general ward, 82.4% of the estimated energy requirement and 102.8% of the protein requirement were met. Despite this, the patient experienced 19.4% weight loss, likely due to underestimation of hypermetabolic demands and delays in EN advancement caused by fluctuating clinical conditions. NST adjusted the nutrition strategy by incorporating high-protein formulas, parenteral nutrition supplementation, and gastrointestinal management. This case report demonstrates the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary nutritional interventions in improving clinical outcomes for neurocritically ill patients.

-

Keywords: Enteral nutrition; Traumatic brain injury; Critical care

INTRODUCTION

Adequate nutritional support is crucial for counteracting the prolonged hypermetabolic and hypercatabolic states, as well as the associated nitrogen loss, that occur in patients with severe brain injuries [

1]. Enteral nutrition (EN) in neurocritically ill patients has been associated with several beneficial outcomes, including attenuation of the catabolic response, prevention of intestinal mucosal atrophy, preservation of lean body mass, and a reduced risk of infections [

2].

Specific guidelines for nutritional support in neurocritically ill patients are limited. The 2016 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN)/Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) guidelines recommend that, similar to other critically ill patients, early EN using a high-protein polymeric formula should be initiated within 24–48 hours post-injury once the patient is hemodynamically stable [

3]. Nonetheless, neurocritically ill patients may encounter challenges in maintaining adequate EN owing to metabolic changes caused by clinical conditions such as increased intracranial pressure, polytrauma, seizures, targeted temperature management (TTM), and pharmacological interventions [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Therefore, this case report discusses the role of the nutrition support team (NST) in actively addressing these challenges and optimizing nutritional strategies affecting EN delivery in a neurocritically ill patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

CASE

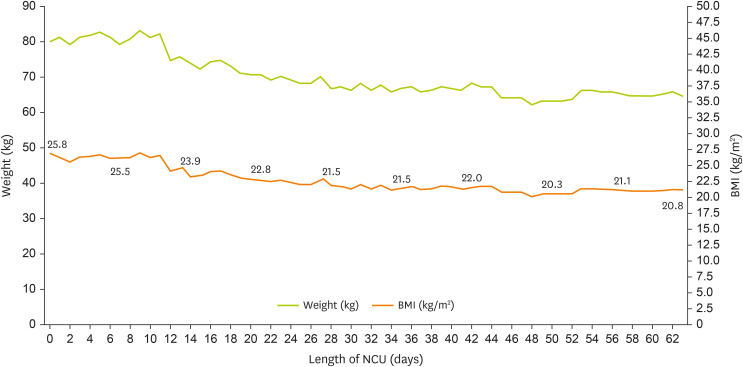

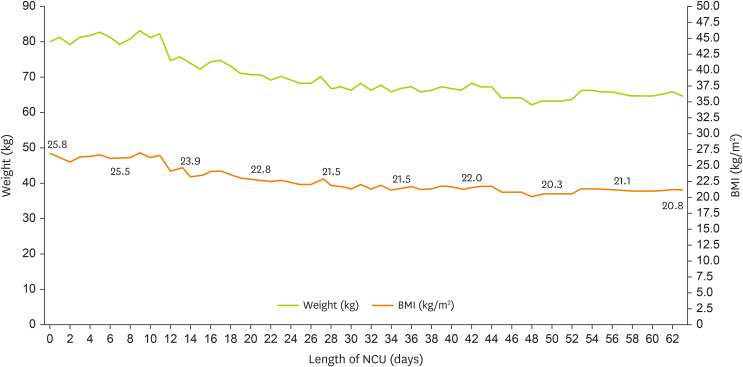

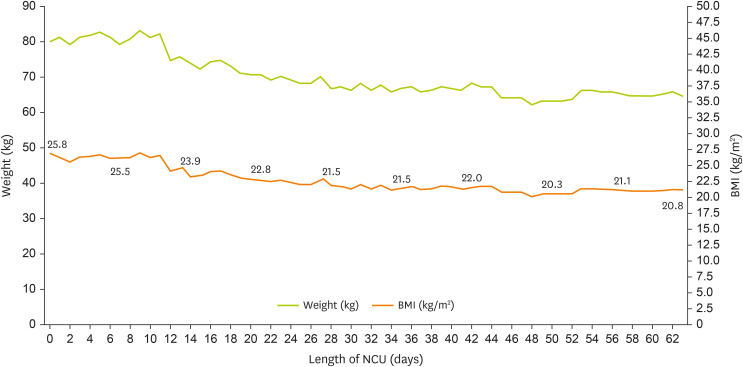

A 56-year-old man with no known comorbidities was involved in a road traffic accident in June 2024. He presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 4 and a modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill score of 1. An initial brain computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multifocal traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, and traumatic subdural hemorrhage. The patient was subsequently transferred to the neuro-intensive care unit (NCU). Additional traumatic injuries included facial bone fractures (zygomatic arch), left-sided pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, multiple rib fractures, and fractures of the sacrum and L5 vertebra. Mechanical ventilation was initiated following endotracheal intubation due to worsening respiratory acidosis and declining mental status. Upon NCU admission, the patient’s height was 176 cm, weight was 80 kg, and body mass index (BMI) was 25.8 kg/m

2. EN was initiated using a standard 1.0 kcal/mL fiber-containing formula at 200 mL/h on NCU day 3 once the patient was hemodynamically stable. Changes in the patient’s weight and biochemical marker levels are presented in

Figure 1 and

Table 1, respectively. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. KC25ZASI0134).

Figure 1

Changes in the patient’s weight during his stay in the NCU.

BMI, body mass index; NCU, neuro-intensive care unit.

Table 1 Changes in the patient’s biochemical marker levels during his stay in the NCU

Table 1

|

Variables |

Length of stay in the NCU (days) |

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

49 |

56 |

63 |

|

Albumin (g/dL) |

4 |

3.8 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.5 |

4 |

|

CRP (mg/dL) |

0.05 |

11.75 |

1.66 |

7.83 |

3.29 |

3.2 |

6.09 |

4.93 |

1.28 |

0.5 |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

13.4 |

9 |

9.6 |

10.2 |

9.5 |

9.2 |

10.6 |

9.7 |

9.5 |

9.6 |

|

Hematocrit (%) |

38 |

26 |

29 |

32.2 |

30.1 |

28.7 |

32 |

30.4 |

29.3 |

29.4 |

|

Platelet (109/L) |

142 |

135 |

217 |

185 |

207 |

177 |

218 |

284 |

274 |

239 |

|

AST (IU/L) |

108 |

61 |

68 |

36 |

37 |

22 |

54 |

26 |

22 |

17 |

|

ALT (IU/L) |

56 |

64 |

66 |

43 |

44 |

23 |

64 |

20 |

16 |

17 |

|

Sodium (mmol/L) |

142 |

137 |

146 |

138 |

144 |

137 |

136 |

140 |

138 |

136 |

|

Potassium (mmol/L) |

3.6 |

3.1 |

3.7 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

4.0 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

Day 3 of NCU stay (days 0–3): 1st NST consultation

After the patient was stabilized, EN was initiated via a nasogastric tube using a standard fiber-containing formula (1.0 kcal/mL) at 200 mL/h, administered thrice daily, resulting in a total administered volume of 600 mL/day. The patient was referred to the NST owing to the anticipated prolonged NCU stay resulting from polytrauma and the need for continued nutritional support. The nutritional requirements were estimated at 1,700 kcal/day (25 kcal/kg/day) based on a simplified weight-based calculation, with a protein goal of 82 g/day (1.2 g/kg/day). The patient, with a BMI of > 25 kg/m

2, was classified as obese, and the nutritional requirements were estimated based on ideal body weight in accordance with the 2023 The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines [

8]. During the initial NST consultation, a switch to a high-protein formula was recommended, along with adjustments to the feeding rate based on gastrointestinal tolerance.

NCU day 5

After an episode of vomiting (~40 mL) and high gastric residual volume (GRV), continuous feeding regimen (40 mL/h via infusion pump) was adjusted. However, owing to a persistently high GRV of 2,035 mL/day, enteral feeding was discontinued overnight, followed by insertion of rectal tube and initiation of natural gastric drainage. Ileus was confirmed via X-ray, after which nil per os (NPO) was maintained. Periodic abdominal X-ray imaging was planned to assess bowel gas patterns, and electrolyte imbalances were corrected accordingly. Abdominal and chest CT scans were planned in response to persistent high fever. Considering the patient’s history of a high GRV, vomiting, and the planned resumption of TTM, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was initiated at 40 mL/h in the afternoon of NCU day 6. At that point, the patient’s body weight had decreased by 5.5 kg (6.9%) compared with that at admission. There was no history of weight gain associated with fluid loading.

NCU day 7

The patient’s mean daily energy and protein intake from TPN reached 1,101.3 kcal and 51.2 g, which corresponded to 64.8% of the estimated energy requirement and 62.7% of the protein requirement, respectively.

NCU day 11

The patient was successfully weaned from ventilator-assisted breathing. EN was reinitiated using a 1.0 kcal/mL high-protein, fiber-containing formula, administered continuously at 20 mL/h. EN and TPN provided 330 kcal with 19.8 g protein and 667.1 kcal with 31 g protein, respectively. During feeding, the GRV peaked at 120 mL and gradually decreased thereafter. TPN was continued until the enteral intake reached 1,000 kcal/day, equivalent to 58.8% of the daily energy requirement. Flushing water (50–200 mL) was administered with each feeding and adjusted to meet the fluid input/output (I/O) targets. Owing to the absence of stool defecation for 12 days following hospital admission, an enema was administered. Despite the continuous use of laxatives (lactulose and magnesium sulfate) and probiotics (Lactobacillus casei variety rhamnosus), along with a fiber-containing formula and adequate hydration, the patient experienced persistent constipation, necessitating the administration of enemas once or twice per week.

Day 20 of NCU stay (days 13–20): 3rd NST consultation

NCU day 17

Enteral feeding was advanced to 1,000 mL/day (1,000 kcal/day, 60 g protein/day) without signs of delayed gastric emptying.

NCU day 20

Following tracheostomy, the NST recommended a gradual increase in EN to meet the target caloric requirements. At this point, the patient’s body weight had decreased by 9 kg (11.2%) compared to that at admission.

Day 27 of NCU stay (days 21–27): 4th NST consultation

NCU day 25

Enteral feeding volume was increased to 1,200 mL/day (1,200 kcal/day, 72 g protein/day), which provided 70.6% of the daily caloric goal and 88% of the daily protein requirement. Despite maintaining this regimen, the patient lost 11 kg of body weight since admission.

Day 39 of NCU stay (days 28–39): 5th NST consultation

NCU day 29

Chest CT, performed in response to acute clinical deterioration observed on the chest X-ray, revealed a left-sided hemothorax. Chest tube and nasogastric tube drainage were initiated following cardiothoracic surgical consultation. The patient was placed on NPO status, and TPN was initiated, delivering 949.6 kcal and 44.2 g of protein per day (55.9% of the energy requirement). Natural drainage was discontinued after 3 days.

NCU day 32

Continuous EN using a standard fiber-containing 1.0 kcal/mL formula was reinitiated at 40 mL/h and was well tolerated. The following day, the feeding rate was increased to 80 mL/h, resulting in a total administered volume of 900 mL/day.

NCU day 39

The feeding regimen was switched to intermittent feeding and increased to 1,200 mL thrice daily (1,200 kcal/day, 48 g protein/day) to achieve the goal, which covered 70.6% of the energy requirement but only 59% of the protein requirement.

Day 46 of NCU stay (days 40–46): 6th NST consultation

NCU day 42

As the standard formula failed to meet the patient’s protein requirements, the NST recommended switching to a high-protein, fiber-containing formula.

Day 59 of NCU stay (days 47–63): 7th NST consultation

NCU day 59

Owing to delayed recovery from weight loss, an increase in enteral feeding volume was recommended, targeting up to 1,400 mL/day (1,400 kcal/day, 84 g protein/day), which provided 82.4% of the energy and 102.8% of the protein requirements.

NCU day 60

Enteral feeding reached 1,400 mL/day. The patient was transferred to the general ward 3 days after reaching this target.

Table 2 summarizes the progression of nutritional intake via enteral and parenteral routes throughout the NCU stay. During the NCU stay, the patient experienced severe weight loss; however, the weight on NCU day 60 was 64.5 kg (BMI 20.8 kg/m

2), which falls within the normal range, and the nutritional status was considered adequate.

Table 2Enteral and PN intake trends during the NCU stay

Table 2

|

Variables |

Length of stay in the NCU (days) |

|

0 |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

35 |

42 |

49 |

56 |

63 |

|

Energy intake (kcal/day) |

534.9 |

1,101.3 |

1,318 |

1,000 |

1,200 |

900 |

1,200 |

1,200 |

1,200 |

1,400 |

|

Protein intake (g/day) |

24.9 |

51.2 |

72.1 |

60 |

72 |

36 |

48 |

72 |

72 |

82.4 |

|

% Energy goal |

31.5 |

64.8 |

77.5 |

58.8 |

70.6 |

44.1 |

70.6 |

70.6 |

70.6 |

82.4 |

|

% Protein goal |

60.5 |

62.7 |

88.2 |

73.4 |

88.1 |

52.9 |

58.8 |

88.1 |

88.1 |

102.8 |

|

% Energy intake through EN |

0 |

0 |

47.1 |

58.8 |

70.6 |

44.1 |

70.6 |

70.6 |

70.6 |

82.4 |

|

% Energy intake through PN |

31.5 |

64.8 |

30.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

% Protein intake through EN |

0 |

0 |

58.8 |

73.4 |

88.1 |

52.9 |

58.8 |

88.1 |

88.1 |

102.8 |

|

% Protein intake through PN |

30.5 |

62.7 |

29.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

DISCUSSION

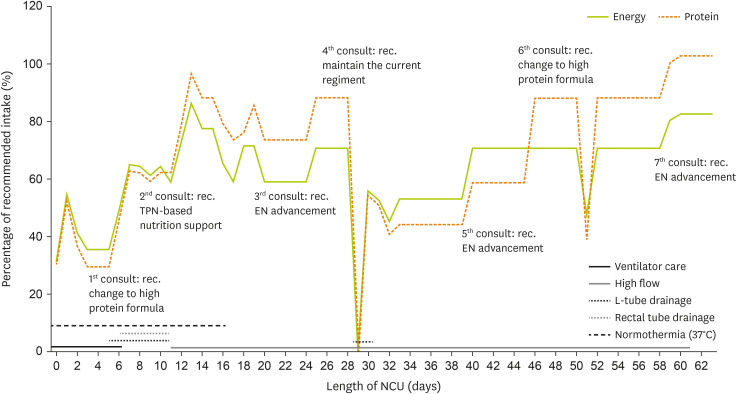

This case report demonstrates the role of the NST in addressing the challenges encountered while maintaining adequate EN and optimizing nutritional strategies that affect EN delivery in a neurocritically ill patient with TBI.

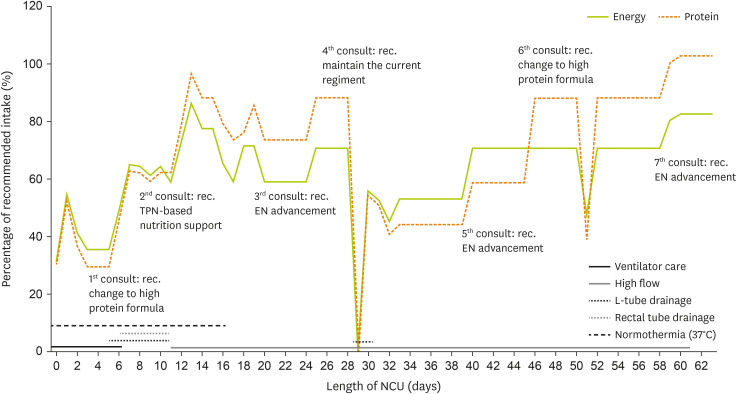

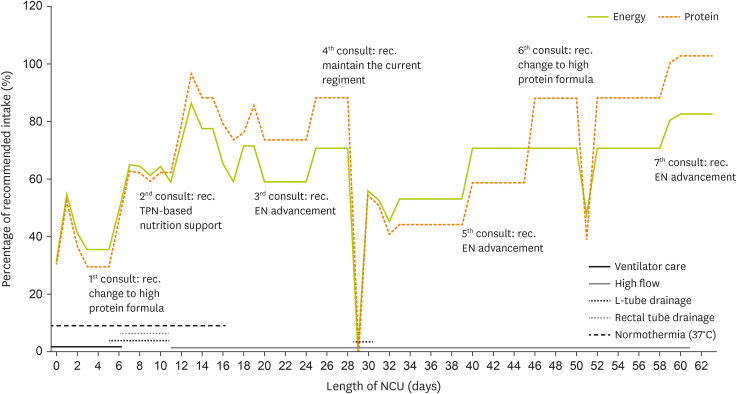

EN was initiated on day 3 after NCU admission, and by day 7, it provided 64.8% of the energy requirement and 62.7% of the protein requirement. Similar to findings from previous studies, ~60% of the energy requirement was achieved between days 3 and 6 [

5,

9]. Protein intake through EN reached only 58.8% by day 13, indicating a delayed achievement compared to the energy intake. However, following the NST recommendation, the formula was switched to a high-protein formulation, enabling 102.8% of the protein requirement to be met by the time the patient was transferred to the general ward. Despite several interruptions in EN delivery, timely supplementation with PN helped maintain adequate overall nutritional status.

Figure 2 illustrates the trends in energy and protein intake based on the patient’s condition during the NCU stay.

Figure 2

Energy and protein intake trends during the NCU stay.

NCU, neuro-intensive care unit; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; EN, enteral nutrition.

The patient experienced 19.4% weight loss during NCU admission, which may have resulted from limitations in meeting the dynamically changing energy demands during the hypermetabolic and catabolic phases of TBI. Severe TBI increases energy expenditure by 135%–200% of the predicted values [

10]. In this case, the patient’s nutritional requirements were estimated using a weight-based formula, which may have been insufficiently adaptive to the hypercatabolic state [

11]. Moreover, the 2016 SCCM/ASPEN guidelines recommend a protein dose of 1.2–2.0 g/kg/day for most critically ill patients, with higher amounts advised for patients with trauma [

3]. However, in the current case, the protein requirement was estimated at 1.2 g/kg/day, which may not have adequately accounted for the increased protein catabolism associated with trauma, potentially contributing to severe weight loss [

9]. Therefore, indirect calorimetry or other objective methods to assess metabolic demand may be essential for providing individualized nutritional support and preventing excessive weight loss in critically ill patients with TBI [

3,

8].

Persistent constipation is another challenge during the NCU stay. The pathophysiology of constipation in patients with TBI is multifactorial, involving neurological impairment, medication effects, and physiological factors such as reduced bowel mobility. The prevalence of bowel dysfunction is significantly higher in patients with neurological injuries than in the general population [

12]. Multifocal trauma may have played a role in worsening gastrointestinal motility in this patient. We believe that active management using laxatives, prokinetic agents, and enemas played a crucial role in improving EN tolerance and progressing toward nutritional goals.

Hypothermia has been associated with delayed gastric emptying, decreased peristalsis, and impaired nutrient absorption [

13]. A study of patients who underwent TTM after cardiac arrest reported that gastric emptying disturbances occurred in 13% of patients during the cooling (32°C–34°C) and rewarming (36.5°C) phases, with incidence decreasing to 9% during the normothermic phase (37.5°C) [

14]. Another study involving 6 patients with intracranial hemorrhage undergoing hypothermia demonstrated a significantly lower mean EN intake (398 kcal/day) compared to those under normothermia (1,006 kcal/day). Notably, 3 patients in the hypothermia group exhibited elevated GRVs prior to the administration of prokinetic agents, and one patient developed mild ileus [

15]. Although studies directly examining the relationship between normothermia and gastrointestinal complications are limited, existing evidence suggests that gastrointestinal adverse events are more prevalent during the hypothermic phase [

14,

15]. The paralytic ileus observed in this case may have resulted from severe physiological stress during the acute phase of critical illness. Therefore, continuous monitoring for gastrointestinal intolerance may be important when administering EN to patients in the NCU, regardless of normothermia treatment.

In conclusion, this case report describes the successful implementation of nutritional interventions by the NST tailored to the dynamic metabolic transitions observed in a patient with TBI in the NCU. The patient experienced multiple challenges contributing to malnutrition, including weight loss due to increased energy and protein demands, delayed advancement of EN due to gastrointestinal intolerance, and persistent constipation associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility. Further research is warranted to better understand the unique metabolic requirements of neurocritically ill patients and to establish evidence-based nutritional guidelines that address their complex needs.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: So E.

Data curation: So E.

Formal analysis: So E.

Investigation: So E.

Methodology: So E.

Project administration: So E.

Supervision: Choo YH.

Visualization: So E.

Writing - original draft: So E.

Writing - review & editing: Choo YH.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weekes E, Elia M. Observations on the patterns of 24-hour energy expenditure changes in body composition and gastric emptying in head-injured patients receiving nasogastric tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1996;20:31-37.

- 2. Mueller CM, Lord LM, Marian M, McClave SA, Miller SJ. Overview of enteral nutrition. In Doley J, Phillips W, eds, ddThe ASPEN adult nutrition support core curriculum. 3rd ed. Silver Spring: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; 2017, pp 213-223.

- 3. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:159-211.

- 4. Kim JH, Choo YH, Kim M, Jeon H, Jung HW, et al. Neurocritical care nutrition: unique considerations and strategies for optimizing energy supply and metabolic support in critically ill patients. J Neurointensive Care 2023;6:84-97.

- 5. Zarbock SD, Steinke D, Hatton J, Magnuson B, Smith KM, et al. Successful enteral nutritional support in the neurocritical care unit. Neurocrit Care 2008;9:210-216.

- 6. Oertel MF, Hauenschild A, Gruenschlaeger J, Mueller B, Scharbrodt W, et al. Parenteral and enteral nutrition in the management of neurosurgical patients in the intensive care unit. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:1161-1167.

- 7. Abdelmalik PA, Dempsey S, Ziai W. Nutritional and bioenergetic considerations in critically ill patients with acute neurological injury. Neurocrit Care 2017;27:276-286.

- 8. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Calder PC, Casaer M, et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr 2023;42:1671-1689.

- 9. Chapple LA, Chapman MJ, Lange K, Deane AM, Heyland DK. Nutrition support practices in critically ill head-injured patients: a global perspective. Crit Care 2016;20:6.

- 10. Foley N, Marshall S, Pikul J, Salter K, Teasell R. Hypermetabolism following moderate to severe traumatic acute brain injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2008;25:1415-1431.

- 11. Bidkar PU. Nutrition in neuro-intensive care and outcomes. J Neuroanaesth Crit Care 2016;3:S70-S76.

- 12. Coggrave M, Norton C, Cody JD. Management of faecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD002115.

- 13. Rincon F. Targeted temperature management in brain injured patients. Neurol Clin 2017;35:665-694.

- 14. Williams ML, Nolan JP. Is enteral feeding tolerated during therapeutic hypothermia? Resuscitation 2014;85:1469-1472.

- 15. Dobak S, Rincon F. “Cool” topic: feeding during moderate hypothermia after intracranial hemorrhage. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:1125-1130.