ABSTRACT

Pediatric kidney disease has a lower prevalence than other pediatric conditions and has a notably different etiology from kidney diseases occurring in adults. Furthermore, the pediatric population is unique in that they experience ongoing growth and development, distinguishing them from adult patients. Consequently, pediatric patients with kidney disease require a more specialized and meticulous nutritional management plan compared with adult patients. To address this need and promote optimal dietary practices for pediatric patients with kidney disease, pediatric nephrologists from the Korean Society of Pediatric Nephrology and nutritionists from the Korean Society of Clinical Nutrition have collaborated to formulate nutritional guidelines specifically tailored to Korean dietary patterns. These guidelines offer detailed, nutrient-specific recommendations regarding the consumption of energy, protein, calcium, phosphorus, and potassium while providing practical, culturally relevant guidance intended to support both pediatric patients and their caregivers.

-

Keywords: Child; Kidney diseases; Nutritional requirements; Republic of Korea

INTRODUCTION

Nutritional management of pediatric patients with kidney disease is particularly challenging because unlike adults, pediatric patients undergo continued growth and development. As a result, providing adequate nutrition for growth while minimizing disease progression and complications is the primary challenge. However, for mitigating kidney disease, several patients and caregivers obtain nutritional information from online sources, which are often inaccurate, leading to the practice of inappropriate dietary restrictions.

To address this issue, pediatric nephrologists from the Korean Society of Pediatric Nephrology and nutritionists from the Korean Society of Clinical Nutrition have collaborated to develop dietary recommendations tailored to the dietary habits of Koreans. These recommendations aim to serve as the standard for nutritional care and dietary management of pediatric patients with kidney disease in Korea and have been structured in a practical format that categorizes key nutrients to ensure comprehensibility for both patients and caregivers. This approach was also adopted to assist healthcare professionals in managing and educating pediatric patients with kidney disease by providing them with helpful guides for nutritional management.

ENERGY IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

The primary dietary energy sources are carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Carbohydrates and proteins each provide 4 kcal/g of energy, whereas fats supply 9 kcal/g of energy. The daily energy requirement for pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the same as that for healthy children and adolescents of the same age (

Table S1) [

1]. Patients with kidney disease often have insufficient dietary intake due to dietary restrictions or reduced appetite, potentially causing protein depletion, weight loss, and delayed growth [

1-

3]. Therefore, adequate energy intake is crucial for maintaining optimal nutritional status and supporting proper growth. In recent years, however, obesity has become a growing concern among children and adolescents, often more so than energy insufficiency. Therefore, tailoring interventions to the individual patient’s condition is essential.

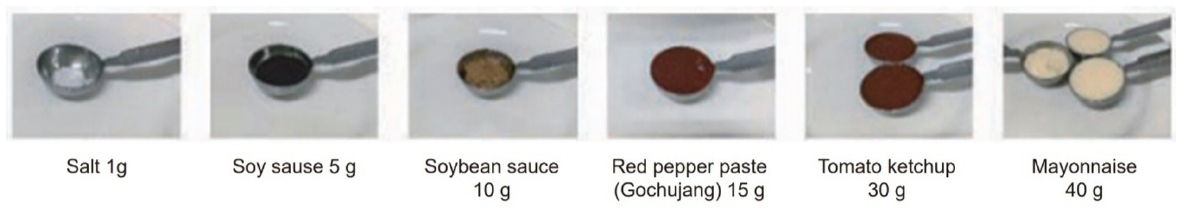

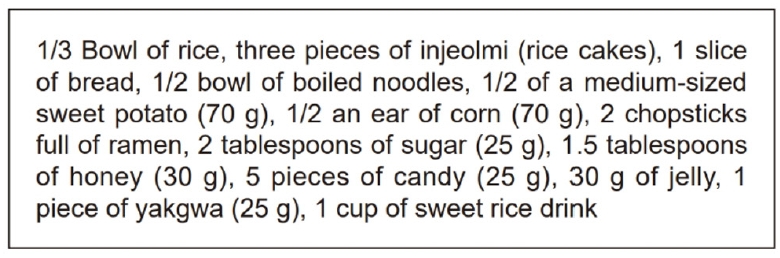

When eating regular meals proves difficult, alternative foods with equivalent calories (kcal) can be selected as substitutes (

Fig. 1) [

4,

5]. To increase energy intake, jam can be added to bread or crackers, and honey or rice syrup can be added to rice cakes. Even with the same ingredients, energy intake can be enhanced by stir-frying, deep-frying, or making pancakes out of the ingredients. Additionally, using sesame oil or perilla oil in the preparation of porridges or side dishes and using olive oil or oriental dressing on salads can help boost energy intake.

Patients with kidney disease who are required to restrict their protein, potassium, and phosphorus intake can use a specialized enteral formula. For infants, increasing the infant formula concentration by reducing the amount of water added can increase the energy content of the formula; however, this method may also increase the protein, sodium, potassium, and phosphorus levels in the formula. Therefore, infant formula concentration should not be altered arbitrarily. Instead, energy modules specifically designed for caloric and nutritional supplementation, such as glucose polymers or fat emulsions, can be added to the formula [

1-

3]. For instance, infants fed formula eight times a day at 100 mL per feeding obtain approximately 560 kcal of energy. By supplementing each 100-mL formula feed with 3 g of an energy-dense additive (e.g., high-calorie powder), the total daily energy intake can be increased to approximately 650 to 700 kcal, representing a 15% to 20% increase in caloric density [

4].

PROTEINS IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Proteins serve as critical components of various body tissues and structures, including muscles, skin, bones, nails, and hair. In the form of hormones, antibodies, and enzymes, proteins play essential roles in growth, physiological function, and life maintenance. Additionally, proteins constitute an important energy source. However, pediatric patients with kidney disease may be required to restrict their protein intake due to impaired renal waste excretion and metabolic acidosis, the extent of which varies with disease severity. Thus, the appropriate protein intake should be carefully determined by considering factors such as disease severity, age, growth velocity, and the necessity for promoting optimal growth and nutritional status.

Dietary sources of protein

Proteins can be sourced from both animals and plants [

4]. Animal-based protein sources mainly include meat, fish, shellfish, eggs, and milk. Except milk, animal-derived foods typically contain 8 g of protein per food exchange unit (a standardized measurement system that allows for interchanging foods within the same food group while ensuring equivalent nutritional value). Plant-based protein sources include grains, vegetables, legumes and their processed products (e.g., tofu), and soy milk. Among these, legumes have the highest protein content, providing 8 g of protein per food exchange unit [

5]. Grains and vegetables each provide approximately 2 g of protein per food exchange unit, whereas soy milk provides 6 g of protein per food exchange unit, which is equivalent to that provided by cow milk (

Table 1) [

5].

Pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome are recommended to maintain a protein intake similar to that prescribed for healthy children of the same age, without increasing or restricting protein intake even during steroid treatment or proteinuria (

Table 2) [

6,

7]. Historically, high-protein diets have been found to compensate for protein losses in nephrotic syndrome; however, instead of improving serum albumin levels, such diets were found to accelerate renal damage due to protein overload. Conversely, studies have demonstrated that low-protein diets slow renal function decline in patients with CKD but exacerbate nutritional deficiencies due to inadequate protein intake [

8-

11]. According to the 2021 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines, protein restriction is recommended for patients with decreased kidney function and proteinuria, although its safety has not been conclusively established in pediatric populations due to concerns about the risk of malnutrition [

12]. An exception to this recommendation is patients with congenital nephrotic syndrome, who may benefit from high-calorie, high-protein diets.

The protein intake of pediatric patients with CKD should be carefully planned to ensure normal growth and adequate nutritional status. Given that strict restriction of protein intake does not necessarily improve the preservation of kidney function, guidelines recommend that pediatric patients with CKD consume the same amount of protein as their healthy peers (

Table S2). However, healthy children and adolescents typically consume more than twice the recommended protein intake. Therefore, patients with CKD must strictly adhere to nutritional guidelines rather than trying to match the high protein consumption of their peers.

Restricting protein intake often inadvertently reduces overall caloric and nutrient consumption. Thus, substantial protein restriction is generally not recommended for patients with stage 1 to 2 CKD. For those with stage 3CKD or higher, guidelines recommend a protein intake that closely aligns with age-specific nutritional requirements (

Table 3) [

1,

2,

6,

7,

13].

A serving of meat weighing approximately 40 g, approximately the size of a ping-pong ball, contains approximately 8 g of protein [

4,

5]. For example, the daily recommended protein intake for a 10-year-old boy is approximately 50 g. If this daily requirement were to be met exclusively through meat, approximately 250 g of meat (approximately six ping-pong ball-sized portions) would be required (

Table 1). However, actual meals typically include rice and vegetables alongside meat. Considering that one bowl of rice contains approximately 6 g of protein, along with vegetable side dishes, a total of 20 to 25 g of protein can be obtained daily through these foods. Therefore, an additional 3 to 4 ping-pong ball-sized meat servings would suffice to meet the protein requirement.

URIC ACID IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Uric acid is the final product of the breakdown of purines. It is primarily obtained via two means: (1) breakdown of the body’s own cells and (2) dietary intake of purine-rich foods. Most uric acid in the body is eliminated by the kidneys through urine. Hyperuricemia can result from either excessive uric acid production or insufficient renal excretion. In adults, hyperuricemia is defined as uric acid levels exceeding 7 mg/dL, whereas in pediatric patients, hyperuricemia is defined as uric acid levels exceeding the 90th percentile for age and sex [

14]. Severe hyperuricemia can cause gout, a condition characterized by the deposition of uric acid crystals in the joints, and contribute to the development of hypertension and worsening kidney function. Thus, dietary management aimed at maintaining normal blood uric acid levels is crucial for pediatric patients with CKD.

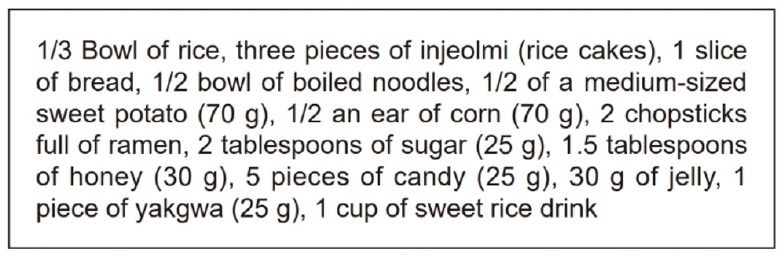

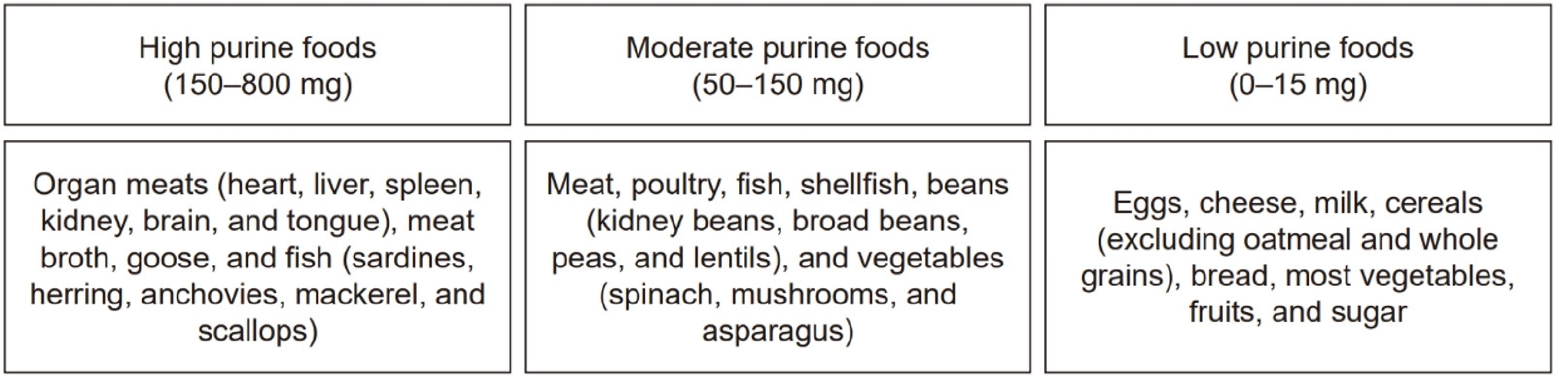

Fig. 2 presents a list of the dietary sources of uric acid classified according to purine content [

4].

Factors elevating uric acid levels

Fat

Excessive fat intake stimulates fatty acid synthesis in the liver, which has been linked to increased purine synthesis, consequently accelerating uric acid production and impairing uric acid excretion [

15]. Therefore, reducing fat intake is important for managing hyperuricemia. To achieve this, studies recommend using alternative cooking methods, such as steaming or grilling, instead of frying or sautéing [

16-

18].

Fructose

Fructose has been established as a prominent risk factor for hyperuricemia [

15-

19], considering that uric acid is produced during fructose metabolism in the liver. Additionally, fructose and its metabolite lactate interfere with uric acid excretion, which quickly raises blood uric acid levels. Therefore, patients with CKD and hyperuricemia should limit their consumption of fructose-rich foods and beverages, including soft drinks, fruit juices, and syrups.

Protein

Traditionally, a low-protein diet has been recommended for the management of hyperuricemia in adults. However, reducing dietary protein intake can inadvertently increase the consumption of refined carbohydrates and foods high in saturated or trans fats. Moreover, protein is essential for growth in pediatric patients. Hence, pediatric patients with CKD should aim to meet their protein requirements rather than excessively restricting their protein intake [

16].

SODIUM IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Sodium, primarily obtained through salt, plays a crucial role in maintaining fluid balance, stable blood pressure, and acid-base balance in the body [

20]. Studies have shown that the sodium intake of Korean children and adolescents exceeds more than twice the sodium intake recommended by the 2020 Korean Dietary Reference Intakes for maintaining good health [

21-

25]. Excessive sodium intake in pediatric patients with CKD can increase blood pressure and potentially exacerbate kidney disease progression. Therefore, reducing sodium intake by identifying high-sodium foods and carefully managing their consumption is vital.

Sodium is abundantly present in condiments or seasonings, pickled foods, processed foods, instant foods, and fast foods.

Table 4 lists the primary dietary sources of sodium for Koreans. Condiments account for nearly 46% of the daily sodium intake [

20]. Therefore, pediatric and adolescent patients with CKD should make concerted efforts to reduce their consumption of sodium-rich condiments and processed foods and limit the frequency of dining out.

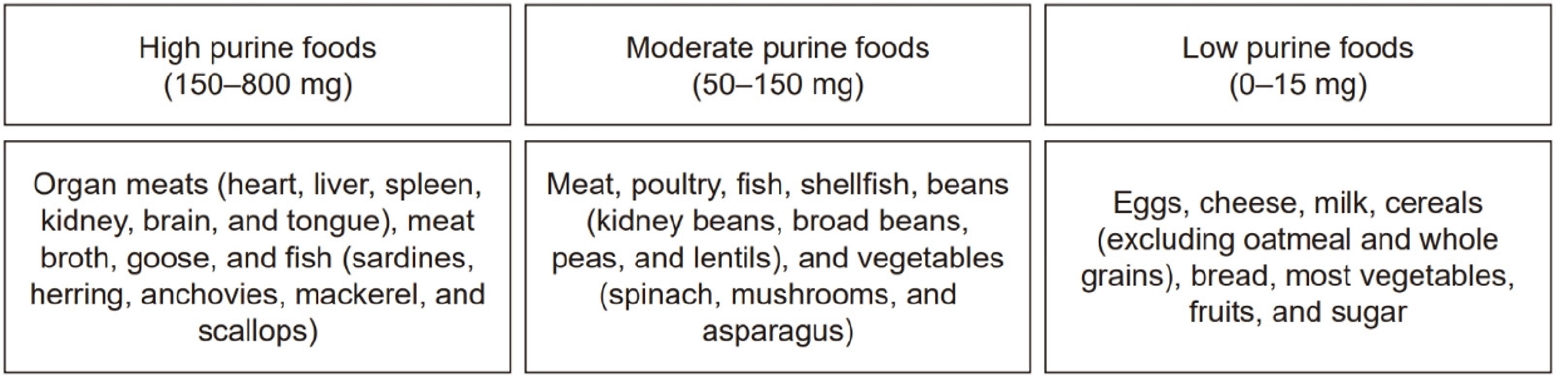

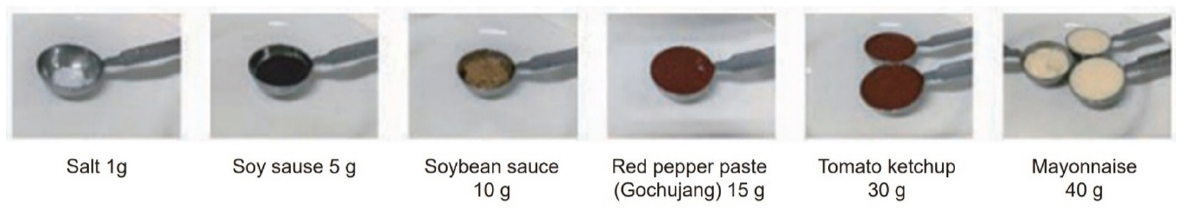

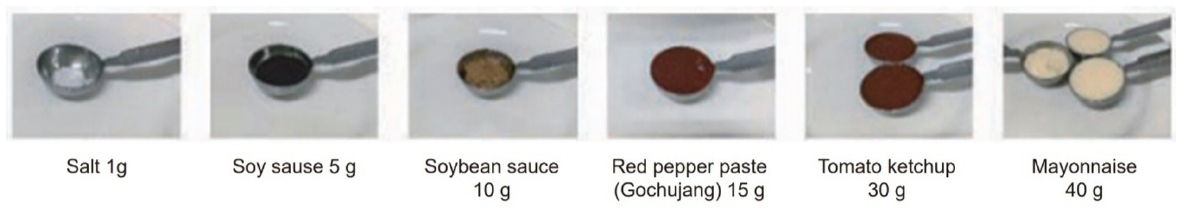

The recommended daily sodium intake for a 7-year-old child is 1,900 mg (

Table S3). Given that 1 g of salt contains approximately 400 mg of sodium, a 7-year-old child can safely consume approximately 5 g of salt per day. Typically, 1 to 2 g of salt is consumed naturally through unprocessed foods, allowing an additional 3 to 4 g of salt to be consumed through condiments or seasonings, which equates to approximately 1 g of salt per meal coming from condiments. A list indicating the amount of various condiments containing 1 g of salt is presented in

Fig. 3 [

26].

Patients with CKD should avoid salted foods, processed foods, fast foods, dried fish, and chemically enhanced seasonings, all of which have a high-sodium content [

26]. Clear soups or rice-water soups (Nurungji-guk) are preferable, given their lower sodium content. Vinegar, lemon juice, wasabi, chili powder, pepper, green onions, onions, garlic, ginger, herbs, perilla oil, and sesame oil can be used to enhance flavor while reducing sodium content. Additional measures for reducing sodium intake include serving sauces as separate dips rather than seasoning soups and side dishes directly, preparing only one side dish with adequate seasoning while leaving the others unseasoned, and using low-sodium condiments [

27,

28].

Processed foods often contain high amounts of sodium for the purpose of preservation. Therefore, caution should be exercised when consuming bread, snacks, convenience store meals, frozen foods, and instant foods [

26]. When eating school meals or dining out, only consume half portions of high-sodium foods, such as braised or pickled dishes and soups. Moreover, individuals can request that the sauce be served separately and use minimal amounts for dipping. Consumption of pickles, ketchup, cheese, bacon, and processed meats should also be minimized [

26-

28].

CALCIUM AND PHOSPHORUS IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Calcium, the most abundant mineral in the body, plays a crucial role in bone health, blood coagulation, nerve conduction, muscle contraction, and hormone secretion. Similarly, phosphorus, the second most abundant mineral, contributes prominently to skeletal structure, regulation of acid-base balance, activation of vitamins and enzymes, and energy metabolism. Calcium and phosphorus concentrations in the body are maintained through integrated regulation involving intestinal absorption, renal reabsorption, and bone exchange. Imbalances that decrease calcium and phosphorus levels can cause bone disorders, such as rickets, osteomalacia, and osteoporosis, whereas high levels of calcium and phosphorus may cause cardiovascular diseases and calcification of blood vessels and kidneys. Thus, appropriate regulation of calcium and phosphorus is crucial in pediatric patients with CKD.

Dietary sources of calcium and phosphorus

Calcium-rich foods include milk, dairy products, anchovies, oysters, dried seaweed, cheese, and tofu. According to the 2018 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [

29], Koreans consume an average of 128.1 mg of calcium per day through milk and dairy, accounting for 29.4% of the daily calcium intake. Milk and dairy products, including manufactured infant formulas, are key calcium sources for infants and children.

Phosphorus is found in almost all animal- and plant-based foods, but it is particularly abundant in protein-rich foods, such as fish, meat, eggs, dairy products, grains, and nuts. The major dietary phosphorus sources for Koreans [

29,

30] include rice and animal-based foods, such as pork (lean meat), chicken, anchovies, milk, and eggs. For infants and children, milk and dairy products serve as more prominent sources of phosphorus than rice and meat.

Phosphorus can be consumed in various forms through natural foods, food additives, and supplements. Food additives are widely used in food processing; thus, frequent consumption of processed foods increases the intake of food additives [

31]. These additives, which are mostly inorganic phosphates, are more readily absorbed than naturally occurring phosphorus in foods. Additionally, phosphates are added to various medications (e.g., antacids and antihypertensive drugs) to aid dispersion and absorption [

32,

33]. Therefore, the assessment of phosphorus intake should consider the consumption of carbonated beverages, processed foods, and medications containing inorganic phosphates.

In Korea, 27 types of phosphates, including potassium phosphate, calcium phosphate, and sodium phosphate, have been approved for use as food additives in food production [

34]. Phosphates function as acidity regulators, emulsifiers, nutrient enhancers, leavening agents, and preservatives. In Korea, phosphates are most commonly used in bakery products, processed foods, and complex seasonings. Although Koreans primarily consume phosphorus through natural agricultural and animal products [

21], the growing trend of processed food consumption among adolescents may increase phosphate intake from food additives.

Pediatric patients with CKD must regularly monitor their calcium and phosphorus intake, including intake from food additives, processed foods, and calcium-containing medications (e.g., calcium-based phosphate binders). Calcium intake should be aligned with the recommended daily allowance for that age (

Table S4) and should ideally not exceed twice this amount. Phosphorus intake should also adhere to age-specific recommendations (

Table S5) while still ensuring adequate nutritional intake. However, given the high phosphorus content in dairy products, fish, and meat, strict adherence to the recommended levels can be challenging, often necessitating the use of phosphate binders to manage phosphorus effectively.

Meal planning should prioritize foods low in phosphorus (

Table 5) [

4]. Given that phosphorus from animal-based foods is absorbed more efficiently than that from plant-based foods, animal proteins should be evenly distributed across meals rather than consumed excessively at one time [

32]. Considering that phosphorus is water-soluble, the phosphorus content of foods can be reduced by boiling them in plenty of water [

31,

35,

36]. After boiling, the cooking water is discarded as it contains high levels of phosphorus. Boiling reduces phosphorus content in vegetables, legumes, and meats by approximately 51%, 48%, and 38%, respectively [

4]. Boiling food for over 30 minutes using a pressure cooker is more effective than using a regular pot. If processed foods are desired, they should be cut into small pieces, boiled, and drained before consumption. Always check the labels on processed foods to identify phosphorus additives (e.g., phosphate compounds) and manage intake carefully.

Breastfeeding is recommended even for infants with CKD [

35]. However, if breastfeeding is not possible and manufactured infant formulas are chosen instead, studies have recommend the use of standard formulas suitable for the infant’s age and weight. As infant formulas advance in stages, their protein and mineral contents increase slightly despite similar caloric contents. Thus, if an infant consumes adequate amounts of formula, maintaining a lower-stage formula might be beneficial to prevent excessive intake of proteins and minerals [

4]. Specifically, infants older than 6 months who primarily rely on formula due to difficulties transitioning to complementary foods may consume excessive amounts of minerals when consuming large amounts of advanced-stage formula. The use of formulas low in phosphorus can be considered after consulting with healthcare providers.

Table 6 compares the nutritional contents of breast milk and infant formulas [

37].

POTASSIUM IN PEDIATRIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Potassium is an essential mineral necessary for maintaining muscle, nerve, and heart function. In patients with decreased kidney function, impaired potassium excretion can cause potassium imbalances and related complications. Therefore, identifying potassium-rich foods and managing their intake as needed is imperative. Pediatric patients with CKD whose potassium levels remain normal can follow the potassium intake recommendations for healthy children (

Table S6). However, patients with hyperkalemia should avoid foods high in potassium and employ cooking methods that lower the potassium content in food (

Table 7) [

37]. Conversely, patients with hypokalemia should prioritize the consumption of potassium-rich foods.

Table 7 lists the dietary sources of potassium in Korean cuisine. Additionally, potassium intake can be influenced by potassium salts used as food additives in various processed foods. Thus, individuals who are prescribed a potassium-restricted diet should carefully check the food ingredient label on processed foods for the content of potassium additives. In Korea, potassium salts approved for use as food additives [

34] have been primarily used as acidity regulators, flavor enhancers, nutrient enhancers, coloring agents, sweeteners, emulsifiers, thickeners, stabilizers, flour treatment agents, bleaching agents, preservatives, and leavening agents. Potassium intake can be increased by consuming more amounts of processed or instant foods instead of fresh foods. Patients with hyperkalemia should therefore evaluate nondietary factors causing potassium imbalance (e.g., adjustments to dialysis prescriptions, medication review) before modifying their dietary intake.

Meal planning for hyperkalemia management

When consuming a regular diet, processed foods containing potassium additives should be avoided. If hyperkalemia persists, the intake of high-potassium foods should be reduced, and cooking methods that lower the potassium content of food should be adopted [

4]. If dietary adjustments fail to control potassium levels, oral potassium binders may be necessary [

38].

Regarding vegetable intake, not all raw vegetables must be blanched. Instead, select low-potassium options and avoid high-potassium varieties. Vegetables can be peeled, and their stems can be removed. Then, they can be sliced thinly or diced and soaked in water (10 times the volume of the vegetables) for at least 2 hours before being rinsed and cooked [

4,

38]. If blanching is preferred, vegetables can be blanched in water five times their volume, boiled thoroughly, and rinsed [

4,

38].

When consuming fruits, the skin should be peeled off before eating. Dried fruits must be consumed with caution because they typically have at least twice the potassium content of fresh fruits [

4]. Canned fruits generally have a lower potassium content and can be consumed safely in moderation, but excessive syrup intake should be avoided [

4].

CONCLUSIONS

Following the dietary recommendations developed jointly by the Korean Society of Pediatric Nephrology and the Korean Society for Clinical Nutrition, pediatric patients with kidney disease in Korea can better establish optimized dietary regimens and nutritional management plans. These recommendations, which reflect essential nutrient-specific recommendations tailored to the Korean dietary context, are expected to serve as a valuable resource not only for patients and caregivers but also for healthcare professionals involved in the management and education of pediatric kidney disease.

NOTES

-

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Methodology: JS, SH. Validation: HGK. Formal analysis: YHA, HKL.

Investigation: all authors. Data curation: all authors. Supervision: HKL. Writing - original draft: YHA. Writing - review & editing: HKL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflicts of interest

None.

-

Funding

This recommendation was supported by the National Institutes of Health research project (2025E110100).

-

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is being submitted simultaneously to Kidney Research and Clinical Practice, Clinical Nutrition Research, and Childhood Kidney Disease, with prior approval from the editors of all three journals.

-

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary materials

Fig. 1.Examples of foods with 100 kcal.

Fig. 2.Classification of foods according to purine content (per 100 g) [

4].

Fig. 3.Amount of condiments containing 1 g of salt (400 mg of sodium) [

26]. Spoon used is 1 tablespoon.

Table 1.Major dietary protein sources according to exchange unit [

5]

Table 1.

|

Source |

Weight |

Estimated serving size |

Protein content (g) |

|

Animal-based foods |

|

|

|

|

Meat |

40 g |

Size of one ping-pong ball |

8 |

|

Fish |

50 g |

Small piece |

8 |

|

Shellfish |

70 g |

1/3 Cup |

8 |

|

Egg |

55 g |

1 Medium-sized egg |

8 |

|

Milk |

200 mL |

1 Cup (pack) |

6 |

|

Plant-based foods |

|

|

|

|

Grains |

70 g |

1/3 Bowl of cooked rice |

2 |

|

Vegetables |

70 g |

1/3 Cup cooked |

2 |

|

Beans |

20 g |

2 Tablespoons |

8 |

|

Tofu |

80 g |

1/4 Block |

8 |

|

Soy milk |

200 mL |

1 Cup (pack) |

6 |

Table 2.Recommended protein intake for healthy children and pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome [

6,

7]

Table 2.

|

Parameter |

Age group |

|

Infant |

Toddler |

Child |

Adolescent |

|

0–6 mo |

7–12 mo |

1–3 yr |

4–8 yr |

9–13 yr |

14–18 yr |

|

Sex |

Both |

Both |

Both |

Both |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Protein (g/kg/day) |

1.5 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.85 |

0.95 |

0.85 |

Table 3.Recommended protein intake for pediatric patients with CKD [

6,

7]

Table 3.

|

Parameter |

Age group |

|

Infant |

Toddler |

Child |

Adolescent |

|

0–6 mo |

7–12 mo |

1–3 yr |

4–8 yr |

9–13 yr |

14–18 yr |

|

Protein (g/kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CKD stage 3 |

1.50–2.10 |

1.20–1.70 |

1.05–1.50 |

0.95–1.35 |

0.95–1.35 |

0.85–1.20 |

|

CKD stage 4–5 |

1.50–1.80 |

1.20–1.50 |

1.05–1.25 |

0.95–1.15 |

0.95–1.15 |

0.85–1.02 |

Table 4.Ranking foods according to sodium content [

21]

Table 4.

|

Rank |

Food item |

Sodium (mg/100 g) |

|

1 |

Salt |

33,417 |

|

2 |

Soy sauce |

5,476 |

|

3 |

Kimchi (Napa cabbage) |

548 |

|

4 |

Ramen (dried noodles and soup) |

1,338 |

|

5 |

Soybean paste |

4,339 |

|

6 |

Red pepper paste |

2,486 |

|

7 |

Bread |

516 |

|

8 |

Salted seafood |

11,826 |

|

9 |

Anchovies |

2,377 |

|

10 |

Noodles |

395 |

|

11 |

Dried seaweed |

7,535 |

|

12 |

Ham/sausage/bacon |

759 |

|

13 |

Ssamjang |

2,619 |

|

14 |

Powdered seasoning |

15,836 |

|

15 |

Rice cake |

261 |

|

16 |

Snacks |

577 |

|

17 |

Cubed radish kimchi |

501 |

|

18 |

Bulgogi marinade |

1,964 |

|

19 |

Young radish kimchi |

510 |

|

20 |

Fish cakes |

699 |

|

21 |

Egg |

131 |

|

22 |

Radish kimchi |

692 |

|

23 |

Buckwheat noodles |

455 |

|

24 |

Sandwich/hamburger/pizza |

378 |

|

25 |

Milk |

36 |

|

26 |

Pork (lean meat) |

49 |

|

27 |

Cheonggukjang |

3,083 |

|

28 |

Black bean sauce |

3,227 |

|

29 |

Cheese |

928 |

|

30 |

Dongchimi |

533 |

Table 5.Foods rich in phosphorus [

4]

Table 5.

|

Food group |

Food item |

|

Grain |

Potatoes, taro, black rice, barley, mung beans, Job’s tears, sorghum, millet, chestnuts, bread, breadcrumbs, oatmeal, corn, and ginkgo nuts |

|

Animal protein |

Dried fish (anchovies and whitebait), fish roe (pollock/cod eggs), liver, ham, beef bone broth, and egg yolks |

|

Dairy product |

Milk, cheese, yogurt, ice cream, and custard cream |

|

Nut |

Peanuts, walnuts, and almonds |

|

Other |

Chocolate, brown sugar, raw sugar, royal jelly, and coke |

Table 6.Nutritional contents of breast milk and infant formulas [

37]

Table 6.

|

Type |

Energy (kcal/100 mL) |

Protein (g/100 mL) |

Calcium (mg/100 mL) |

Phosphorus (mg/100 mL) |

Potassium (mg/100 mL) |

Sodium (mg/100 mL) |

|

Breast milk |

61 |

1.1 |

27 |

14 |

48 |

15 |

|

Infant formula, step 1 (up to 6 mo) |

71 |

1.7 |

77 |

45 |

98 |

23 |

|

Infant formula, step 2 (6–12 mo) |

71 |

1.8 |

89 |

52 |

103 |

24 |

|

Infant formula, step 3 (after 12 mo) |

67 |

2.4 |

119 |

73 |

130 |

26 |

|

Infant formula, low-phosphate |

70 |

2.0 |

52 |

12 |

63 |

20 |

Table 7.Dietary sources of potassium (mg/serving) [

37]

Table 7.

|

Food group |

Food item (serving size, g) |

Potassium (mg) |

|

Vegetable |

Dried seaweed (2) |

8.6 |

|

Bean sprouts (70) |

58.8 |

|

Seaweed sheets (2) |

70.1 |

|

Onion (70) |

101.5 |

|

Cucumber (70) |

112.7 |

|

Soybean sprouts (70) |

152.6 |

|

Zucchini (70) |

156.8 |

|

Cabbage (70) |

168.7 |

|

Kimchi (50) |

177.5 |

|

Radish (70) |

182.7 |

|

Lotus root (40) |

191.2 |

|

Carrot (70) |

209.3 |

|

Bok choy (70) |

255.2 |

|

Broccoli (70) |

255.5 |

|

Chard (70) |

393.4 |

|

Spinach (70) |

483.7 |

|

Chamnamul (70) |

538.0 |

|

Grain |

Rice (70) |

14.0 |

|

Boiled noodles (90) |

6.3 |

|

Spaghetti (boiled, 90) |

26.1 |

|

Potato (140) |

522.9 |

|

Sweet potato (70) |

262.5 |

|

Corn (70) |

212.1 |

|

Fat |

Almonds (8) |

60.7 |

|

Sesame oil (5) |

2.8 |

|

Dairy |

Soy milk (200) |

304.0 |

|

Milk (200) |

284.0 |

|

Fruit |

Blueberry (80) |

56.0 |

|

Persimmon (50) |

66.0 |

|

Apple (80) |

88.2 |

|

Mango (70) |

99.4 |

|

Lychee (70) |

119.0 |

|

Mandarin (120) |

121.2 |

|

Grapes (80) |

133.0 |

|

Pear (110) |

136.4 |

|

Orange (100) |

158.5 |

|

Watermelon (150) |

163.5 |

|

Banana (50) |

177.5 |

|

Pineapple (200) |

194.0 |

|

Kiwi (80) |

218.4 |

|

Strawberry (150) |

229.5 |

|

Plum (150) |

246.0 |

|

Peach (150) |

324.0 |

|

Nectarine (150) |

346.5 |

|

Melon (120) |

448.8 |

|

Avocado (100) |

485.0 |

|

Korean melon (150) |

675.0 |

|

Cherry tomato (300) |

731.5 |

|

Tomato (350) |

1,006.3 |

|

Animal protein |

Chicken (40) |

130.8 |

|

Pork (40) |

127.2 |

|

Beef (40) |

132.3 |

|

Anchovy (15) |

79.65 |

|

Egg (55) |

69.9 |

|

Quail egg (40) |

67.8 |

|

Tofu (80) |

105.6 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Shaw V, Polderman N, Renken-Terhaerdt J, et al. Energy and protein requirements for children with CKD stages 2-5 and on dialysis-clinical practice recommendations from the Pediatric Renal Nutrition Taskforce. Pediatr Nephrol 2020;35:519-31.

- 2. KDOQI Work Group. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in children with CKD: 2008 update: executive summary. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:S11-104.

- 3. Kleinman RE, Greer FR. Pediatric nutrition. 8th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2020.

- 4. Korean Dietetic Association. Manual of medical nutrition therapy. 4th ed. Korean Dietetic Association; 2022.

- 5. Korean Diabetes Association. Guidelines for the use of food exchange lists for diabetes meal planning. 4th ed. Korean Diabetes Association; 2023.

- 6. Kleinman RE, Greer FR. Pediatric nutrition. 7th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2014.

- 7. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Pediatric nutrition care manual. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2017.

- 8. Polderman N, Cushing M, McFadyen K, et al. Dietary intakes of children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2021;36:2819-26.

- 9. Watson AR, Coleman JE. Dietary management in nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1993;69:179-80.

- 10. Hoffman JR, Falvo MJ. Protein - which is best? J Sports Sci Med 2004;3:118-30.

- 11. Eskandarifar A, Fotoohi A, Mojtahedi SY. Nutrition in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. J Ped Nephrology 2017;5:1-3.

- 12. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerular Diseases Work Group. KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 2021;100:S1-276.

- 13. Nelms CL, Shaw V, Greenbaum LA, et al. Assessment of nutritional status in children with kidney diseases-clinical practice recommendations from the Pediatric Renal Nutrition Taskforce. Pediatr Nephrol 2021;36:995-1010.

- 14. Moulin-Mares SR, Zaniqueli D, Oliosa PR, Alvim RO, Bottoni JP, Mill JG. Uric acid reference values: report on 1750 healthy Brazilian children and adolescents. Pediatr Res 2021;89:1855-60.

- 15. Lima WG, Martins-Santos ME, Chaves VE. Uric acid as a modulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Biochimie 2015;116:17-23.

- 16. Kubota M. Hyperuricemia in children and adolescents: present knowledge and future directions. J Nutr Metab 2019;2019:3480718.

- 17. de Oliveira EP, Burini RC. High plasma uric acid concentration: causes and consequences. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2012;4:12.

- 18. Yokose C, McCormick N, Choi HK. The role of diet in hyperuricemia and gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021;33:135-44.

- 19. Siqueira JH, Mill JG, Velasquez-Melendez G, et al. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and fructose consumption are associated with hyperuricemia: cross-sectional analysis from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Nutrients 2018;10:981.

- 20. Hall JE, Hall ME. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology. 14th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- 21. Ministry of Health and Welfare; The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary reference intakes for Koreans 2020. The Korean Nutrition Society; 2020.

- 22. Kweon S, Oh K. Food sources of nutrient intake in Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Wkly Rep 2019;12:1137-40.

- 23. Park SK, Lee JH. Factors influencing the consumption of convenience foods among Korean adolescents: analysis of data from the 15th (2019) Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. J Nutr Health 2020;53:255-70.

- 24. Kim MG. The relationship between parental sodium intake and adolescent sodium intake. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc 2018;19:453-62.

- 25. Kang M, Choi SY, Jung M. Dietary intake and nutritional status of Korean children and adolescents: a review of national survey data. Clin Exp Pediatr 2021;64:443-58.

- 26. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). e mildly seasoned table our body desires. Vol. 10 [Internet]. MFDS; 2021. [cited 2025 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/portal/cookrcp/cookRcpBookDtl.do

- 27. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Customized meal management guide for the new middle-aged (aged 50–64): for the general public [Internet]. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2021. [cited 2025 Apr 24]. Available from: https://foodsafetykorea.go.kr/portal/board/boardDetail.do?bbs_no=NUTRI01&menu_grp=MENU_NEW03&menu_no=4852&ntctxt_no=1083151&utm_source=chatgpt.com

- 28. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Cooking manual for healthy menus with reduced sodium. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2015.

- 29. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Korea National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2018. KDCA; 2019.

- 30. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Korea National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2020. KDCA; 2021.

- 31. McAlister L, Pugh P, Greenbaum L, et al. The dietary management of calcium and phosphate in children with CKD stages 2-5 and on dialysis-clinical practice recommendation from the Pediatric Renal Nutrition Taskforce. Pediatr Nephrol 2020;35:501-18.

- 32. Nelson SM, Sarabia SR, Christilaw E, et al. Phosphate-containing prescription medications contribute to the daily phosphate intake in a third of hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 2017;27:91-6.

- 33. Sherman RA, Ravella S, Kapoian T. The phosphate content of prescription medication: a new consideration. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2015;49:886-9.

- 34. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Standards and specifications for food additives: notification no. 2022-55. MFDS; 2022.

- 35. Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:S1-107.

- 36. Cupisti A, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Management of natural and added dietary phosphorus burden in kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 2013;33:180-90.

- 37. National Institute of Agricultural Sciences; Rural Development Administration. Korean food composition table. 10th ed. National Institute of Agricultural Sciences; 2020.

- 38. Desloovere A, Renken-Terhaerdt J, Tuokkola J, et al. The dietary management of potassium in children with CKD stages 2-5 and on dialysis-clinical practice recommendations from the Pediatric Renal Nutrition Taskforce. Pediatr Nephrol 2021;36:1331-46.

, Hee Gyung Kang1,2

, Hee Gyung Kang1,2 , Jiyoung Song3

, Jiyoung Song3 , Sangmi Han4

, Sangmi Han4 , Eujin Park5

, Eujin Park5 , Jin-Soon Suh6

, Jin-Soon Suh6 , Jeong Yeon Kim7

, Jeong Yeon Kim7 , Min Ji Park8

, Min Ji Park8 , Keum Hwa Lee9

, Keum Hwa Lee9 , Seon Hee Lim10

, Seon Hee Lim10 , Kyeong Hun Shin11

, Kyeong Hun Shin11 , Hyunji Ko12

, Hyunji Ko12 , Hyun Joo Lee13

, Hyun Joo Lee13 , Eunyoung Jeong14

, Eunyoung Jeong14 , Jinsu Kim15

, Jinsu Kim15 , Sohyun Park15

, Sohyun Park15 , Eonju Choi16

, Eonju Choi16 , Yuri Seo3

, Yuri Seo3 , Kyooyung Oh3

, Kyooyung Oh3 , Jin Kyoung Kim17

, Jin Kyoung Kim17 , Hyun Kyung Lee18

, Hyun Kyung Lee18