ABSTRACT

-

Objective

Achieving glycemic control is essential in the prevention and management of metabolic disorders, with several dietary strategies having been proposed. Meal sequence, which is defined as the order of food consumption while maintaining the overall composition and intake, may attenuate postprandial glycemic responses. This systematic review aimed to assess the effects of meal sequences on postprandial glycemic responses in healthy adults and explore its potential as a preventive strategy for glycemic control.

-

Methods

Literature published between January 2015 and March 2025 in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, KoreaMed, and RISS was searched using the keywords “healthy adult,” “food order,” “meal sequence,” and “glucose response.”

-

Results

Among the 2,442 records identified, one randomized controlled trial, four randomized crossover studies, and one repeated-measures design with a total of 107 participants aged 20–36.7 years met the inclusion criteria. Most of the studies reported that consuming vegetables, fruits, or protein-rich foods before carbohydrate-rich foods reduced postprandial glucose responses and incremental area under the curve compared with mixed or carbohydrate-first meals. These effects were also noted in randomized controlled trials and randomized crossover design.

-

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that adjusting the order of food consumption can effectively mitigate acute postprandial glucose responses in healthy individuals. Further large-scale and long-term randomized controlled trials across diverse populations and standardized protocols are warranted to strengthen the evidence base.

-

Keywords: Meal sequence; Blood glucose; Glycemic control; Insulin; Healthy volunteers

INTRODUCTION

Blood glucose control plays an important role in maintaining metabolic health and preventing chronic diseases. Persistent hyperglycemia increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and neuropathy [

1-

3], which not only reduces quality of life but also has significant socioeconomic burden [

4,

5].

The World Health Organization and the American Diabetes Association have highlighted diabetes prevention and early intervention as critical public health strategies, shifting focus beyond treatment-centered approaches [

6,

7]. Several studies have shown that lifestyle modifications can effectively prevent or delay the onset of diabetes in individuals with prediabetes, which is characterized by borderline elevations in blood glucose levels [

8-

10]. Therefore, preventive strategies for glycemic management have become increasingly important.

Dietary strategies for glycemic control have mostly focused on macronutrient composition and the amount and type of carbohydrates consumed as postprandial blood glucose responses reportedly vary depending on the intake and ratio of carbohydrates, protein, fat, and dietary fiber [

11-

14]. Meal sequence, which is the order of consumption of food groups, has gained increasing attention as a novel intervention strategy for glycemic control. Consuming fiber- and protein-rich foods before carbohydrates attenuates postprandial glucose responses, potentially through mechanisms such as delayed gastric emptying and enhanced glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion [

15].

Compared to consuming carbohydrate-rich food first, consuming protein or vegetables beforehand significantly decreased postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Lee et al. [

16] reported that consuming proteins first lowered the incremental area under the curve (iAUC) and incremental glucose peak (iGp) by up to 55% and 1.9 mmol/L in normal-weight adults, and by 41.2% and 1.0 mmol/L in overweight/obese individuals, respectively. Additionally, a protein-vegetable–first sequence reduced the iAUC by 38.8% and iGp by 45.8%, with similar benefits seen in the vegetable-first group. These results indicate that modifying either the composition or the order of meals may be an effective dietary approach for managing postprandial glycemia.

However, most studies in this area are limited by small sample sizes, short intervention durations, and heterogeneity in study design, meal composition, and outcome measurements. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically review the literature regarding the effects of meal sequence on postprandial blood glucose responses in healthy adults and explore its potential as a dietary strategy for glycemic control.

METHODS

Study design

This study systematically reviewed the effects of meal sequence on blood glucose responses in healthy adults. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

17].

Using KoreaMed, RISS, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science Domestic, and international literature were searched from March 17 to March 24, 2025, targeting studies published between January 2015 and March 2025. Studies were included if they included meal sequence interventions in healthy adults and evaluated blood glucose responses. The main search terms included “healthy adult,” “food order,” “meal sequence,” “glucose response,” and “glucose excursion” (

Table 1,

Table S1).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study population were adults aged ≥19 years; (2) included meal sequence interventions; and (3) analyzed postprandial blood glucose or related hormone responses. Studies were excluded if (1) they included individuals aged <19 years, animals, patients with medical conditions, or postmenopausal women, (2) were unrelated to the research topic (e.g., interventions not related to food intake, or outcomes unrelated to glucose metabolism), (3) were not published in Korean or English, (4) were reviews, letters, editorials, or other non-original research, and (5) had inaccessible full texts.

“Healthy adults” was defined according to the eligibility criteria in the included studies. Specifically, healthy adults were defined as individuals aged ≥19 years without any metabolic, genetic, or chronic diseases as indicated in the original studies. Participants were required to have a normal glycemic status, no history of medication intake that affected glucose or insulin metabolism, and no clinical conditions predisposing them to altered postprandial glycemic responses. The exclusion criteria also comprised current smokers, individuals with gastrointestinal disorders or previous gastrointestinal surgery, and those with food allergies relevant to the test interventions. Body mass index (BMI) was not a primary exclusion criterion due to the variability in BMI ranges across the included studies.

All phases of the systematic review, including literature search, study selection, data extraction, and synthesis, were conducted by a single investigator (JK) under the supervision of a faculty member specializing in nutrition who provided methodological guidance and oversight throughout the review process. To reduce potential bias and ensure methodological rigor, screening and extraction were guided by predefined eligibility criteria and standardized forms.

Data on study design, participant characteristics, meal composition and sequence, intervention methods, outcome variables, measurement techniques, and primary findings were systematically extracted. All extracted data and study classifications underwent iterative verification to ensure the accuracy and internal consistency of the results.

Risk-of-bias assessment

After completing the study selection process, the methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using two risk-of-bias assessment tools. For randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 for individually randomized parallel-group trials (RoB2-IRPG) was used. For studies employing randomized crossover or repeated-measures designs, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 for crossover trials (RoB2-crossover) was used. All evaluations were performed using an intention-to-treat approach, focusing on the effect of assignment to intervention. The RoB 2.0 tool comprises five bias domains, namely bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measuring the outcome, and bias in selecting the reported result. Each signaling question was rated as “yes,” “probably yes,” “probably no,” “no,” or “no information.” Based on the responses to these questions, domain-level judgments were determined using the domain-specific algorithms provided by the RoB 2.0 framework and were classified as low risk of bias, some concerns, or high risk of bias.

RESULTS

Search results and general characteristics

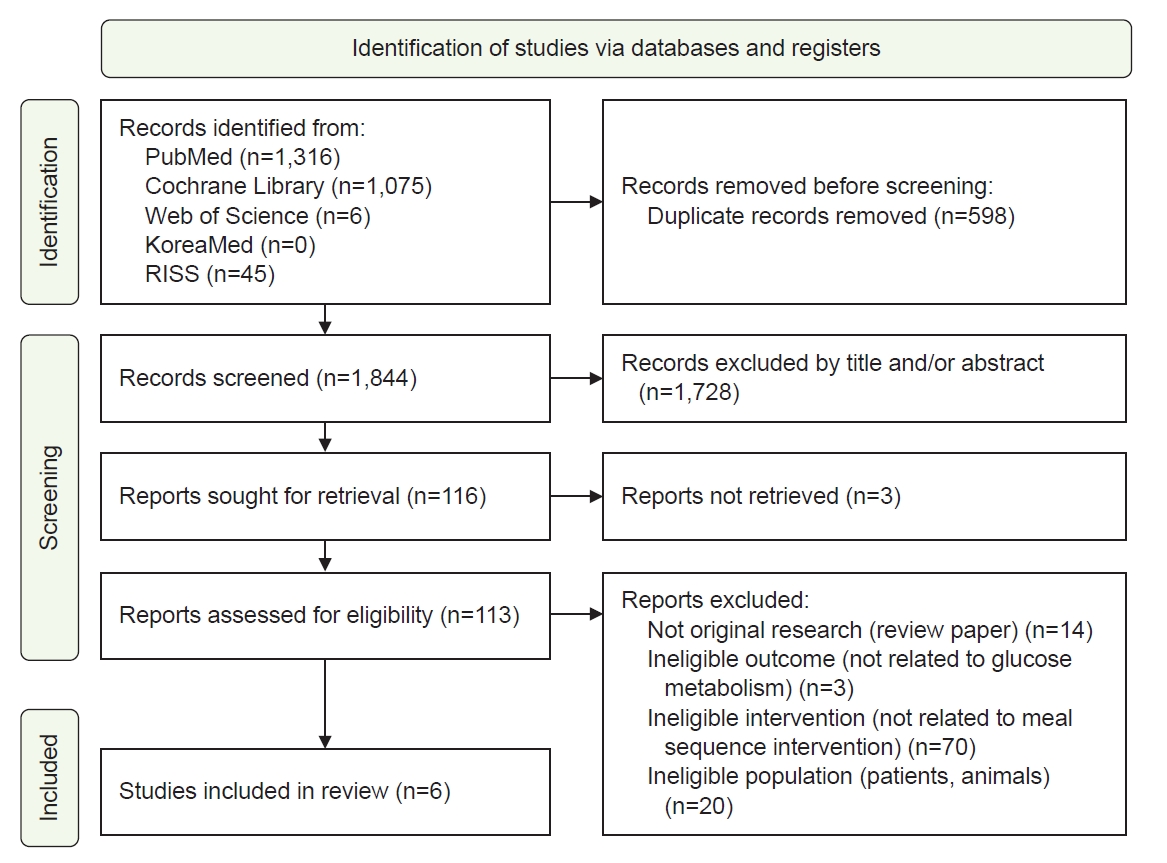

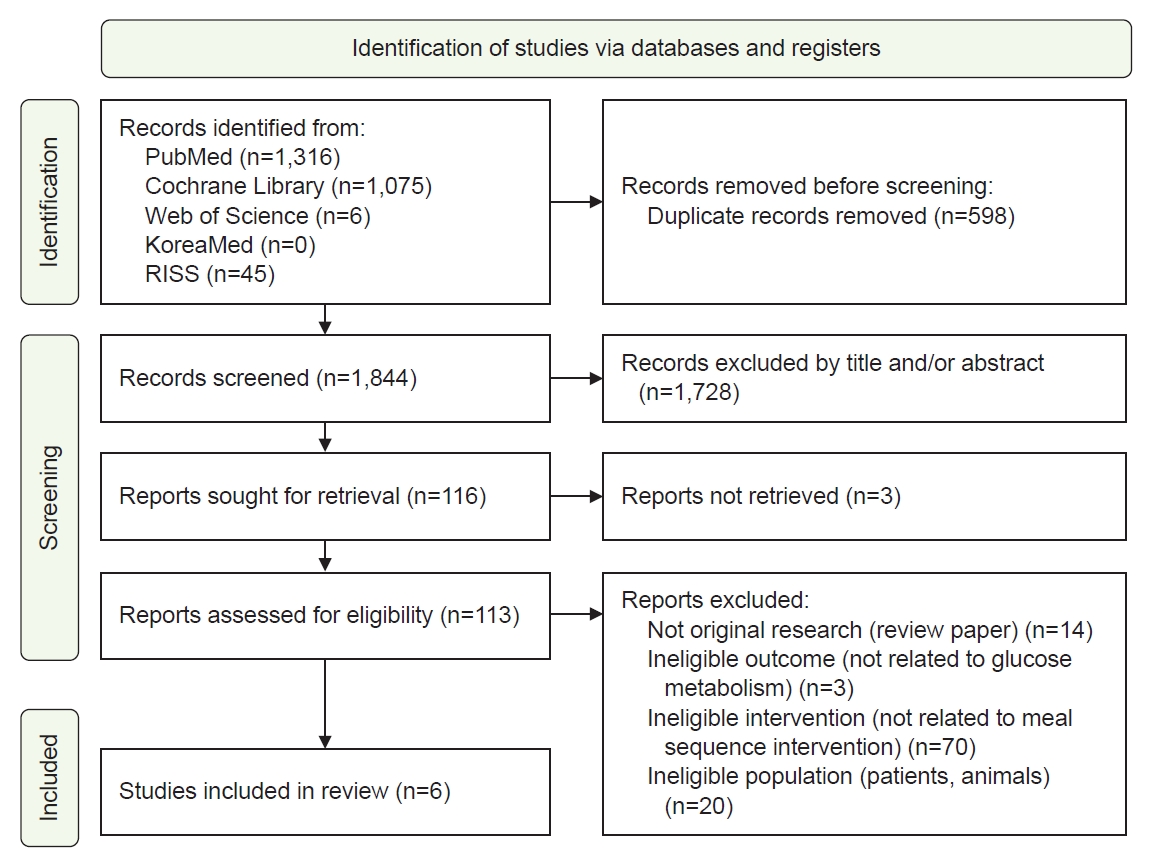

Overall, 2,442 articles were retrieved, and 598 duplicates were removed. After screening the titles and abstracts of the remaining 1,844 articles, 1,728 were further excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the 116 remaining articles were reviewed, and six studies were included in the final analysis (

Fig. 1).

Among the six studies, one was an RCT, four were randomized crossover studies, and one used a repeated-measures design. The studies were performed in Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, and Japan and included 107 participants with a mean age ranging from 20 to 36.7 years. The intervention periods ranged from 3 to 7 days. Four studies had a washout period of 3 to 10 days, while two studies administered the intervention continuously. The meal sequence interventions involved consuming vegetables or fruits, meat, or rice first, or consuming all meal components together. Postprandial glucose responses were analyzed using blood glucose levels, and several studies also assessed levels of incretin hormones, such as insulin, GLP-1, and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP). The detailed characteristics and results of each study are shown in

Table 2, with additional methodological details shown in

Table S2.

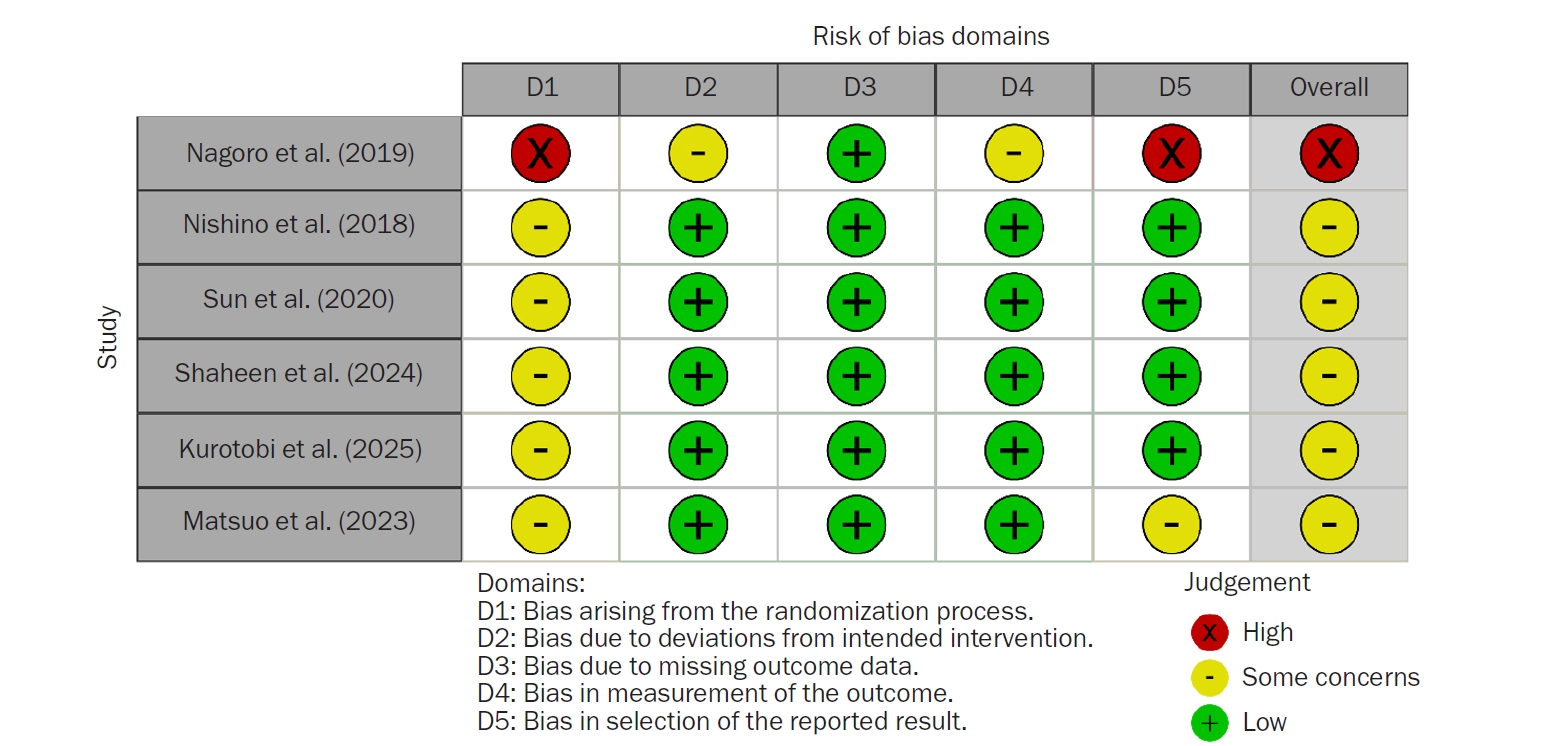

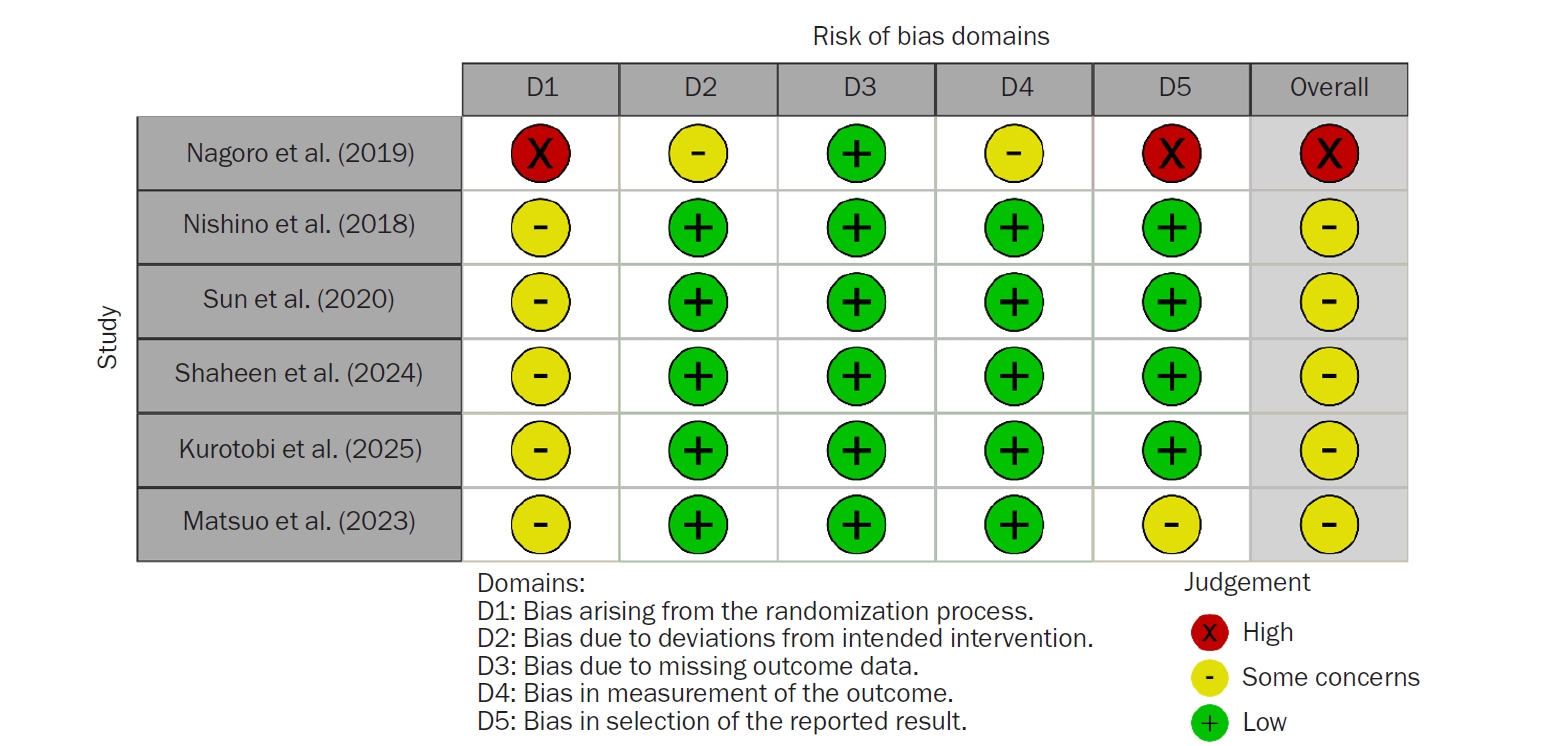

The results of the risk-of-bias assessment for the six included studies are shown in

Fig. 2. Regarding bias arising from the randomization process, five studies (83.3%) had some concerns, and one study (16.7%) had a high risk of bias. Regarding bias due to deviations from intended interventions, five studies (83.3%) had a low risk of bias, while one study (16.7%) had some concerns. Regarding bias due to missing outcome data, all studies had a low risk of bias. Regarding bias in the measurement of the outcome, five studies (83.3%) had a low risk of bias, and one study (16.7%) had some concerns. Regarding bias in selecting the reported result, four studies (66.6%) had a low risk of bias, one study (16.7%) had some concerns, and one study (16.7%) had a high risk of bias.

Across the included studies, consuming vegetables, fruits, or meat before carbohydrates was generally linked to lower postprandial glucose levels or reduced glycemic variability compared to consuming rice first or eating all components together.

Nagoro et al. [

18] performed a 3-day intervention involving 30 healthy adults in Indonesia. Postprandial glucose levels at 1 hour were significantly lower in the banana-only and banana–broccoli groups than in the rice-only control group (P<0.001). Nishino et al. [

19] studied eight healthy Japanese adults over 3 days with a 7-day washout period. The group that consumed salad–pork–carbohydrate-rich foods (rice, steamed pumpkin, and orange) in sequence had significantly lower blood glucose (P<0.05) and insulin (P<0.01) levels at 30 minutes postprandially compared to the group that consumed carbohydrate-rich foods–salad–pork. Additionally, there was a significant difference among the three groups in serum insulin levels (AUC

0–120; P=0.0449). Sun et al. [

20] performed a 5-day intervention with a 7-day washout period on 16 healthy Chinese adults in Singapore. The group that consumed vegetables–chicken breast–rice in sequence had significantly lower glucose levels at 15, 30, and 45 minutes postprandially compared to the group that consumed all items together and the group that consumed rice first (P<0.05). At 30 minutes postprandially, serum insulin levels were significantly lower in the vegetables-first group than in the rice-first group (P<0.05). Shaheen et al. [

21] performed a 2-day intervention with a 7- to 10-day washout period on 18 healthy Arab adults. Blood glucose levels at 30 minutes postprandially were significantly lower in the group that consumed chicken breast and salad first followed by rice compared to the group that consumed a mixed meal (P=0.001). Kurotobi et al. [

22] performed a 7-day intervention on 29 healthy Japanese adults using continuous glucose monitoring over 4 hours. The group that consumed nonrice foods first had significantly lower postprandial glucose levels compared to the group that consumed rice first or mixed-intake groups (P<0.05). Notably, the −15 beef group had the lowest average postprandial glucose levels, indicating a potential benefit of consuming noncarbohydrate foods first.

In contrast, Matsuo et al. [

23], using a repeated-measures design, reported that consuming meat first significantly reduced blood glucose levels at all-time points except at 120 minutes postprandially (P<0.05). However, no significant differences were noted when vegetables were consumed first, except at 90 minutes.

In summary, most studies showed lower postprandial glucose responses when fiber- or protein-rich foods were consumed before carbohydrates, although the magnitude and consistency of effects varied across meal sequence conditions.

DISCUSSION

Across the six included studies, consuming vegetables, fruits, or protein first generally resulted in lower postprandial blood glucose levels or reduced glycemic variability compared to consuming a mixed meal or carbohydrates first. RCTs and crossover studies generally showed significant reductions in postprandial glucose levels and iAUC when vegetables were consumed first before carbohydrate-rich foods.

Meal sequence interventions represent a straightforward strategy to improve acute postprandial glucose responses by simply altering the order of food consumption while maintaining similar overall meal compositions and energy intake. Consumption of fiber-rich vegetables, fruits, and protein-rich foods first is emphasized, and several physiological mechanisms explain these effects. Viscous dietary fibers absorb water and form high-viscosity gels in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby delaying gastric emptying and nutrient transit through the small intestine. This mechanism reduces the interaction of nutrients with digestive enzymes, modulating glucose absorption rates and mitigating the elevation of postprandial blood glucose; this is supported by previous studies. From 22 RCTs in patients with type 2 diabetes, Mao et al. [

24] reported that dietary fiber intake significantly improved glycemic indices and insulin sensitivity. Similarly, Lu et al. [

25] reported that viscous dietary fiber supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes significantly reduced hemoglobin A1c and fasting blood glucose levels. Giuntini et al. [

26] also summarized that soluble fibers, such as β-glucan, psyllium, glucomannan, and pectin, regulate glycemic responses by increasing gastric viscosity, thereby slowing gastric emptying and intestinal transit. Additionally, fermentation by the gut microbiota generates short-chain fatty acids that attenuate hepatic gluconeogenesis and stimulate GLP-1 and peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) secretion, thereby enhancing insulin secretion and satiety. These findings strongly support the observed improvements in postprandial glycemia when vegetables and fruits are consumed first during a meal.

Protein intake also contributes to the regulation of postprandial glycemic response. In their review, Anjom-Shoae et al. [

27] reported that amino acids and peptides derived from protein-rich foods stimulate gastrointestinal L cells, thereby promoting GLP-1, GIP, and PYY secretion. Protein also delays gastric emptying, thereby attenuating postprandial glucose responses. RCTs that employed protein preloads before carbohydrate ingestion also reported a significant reduction in glucose iAUC in both healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes. In a randomized crossover trial, Ma et al. [

28] reported that a whey protein preload in patients with type 2 diabetes significantly delayed gastric emptying, increased GLP-1, GIP, and cholecystokinin secretion, and reduced glucose iAUC to nearly half of the control condition. In another randomized crossover trial involving healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes, Ekberg et al. [

29] similarly reported that a protein-enriched meal significantly reduced the glucose iAUC and insulin-to-glucagon ratio compared with a carbohydrate-enriched meal.

While the feasibility of a meta-analysis was thoroughly assessed, the included studies had substantial methodological and clinical heterogeneity that was evident in study designs (e.g., RCTs, randomized crossover, and repeated-measures designs), intervention protocols (meal composition and intake sequence), and outcome measures, including postprandial glucose levels, iAUC, and hormonal responses. Additionally, inconsistencies in measurement time points across the studies precluded robust quantitative synthesis. Thus, a narrative synthesis was used to interpret the findings as a meta-analytic approach was deemed inappropriate due to the high degree of heterogeneity.

This review has several limitations. First, the heterogeneity in study designs and outcome measures limited direct comparisons and synthesis results. Second, most of the studies only measured short-term acute responses, making it difficult to extrapolate the findings to long-term glycemic control or diabetes-related complication prevention in real-world settings. Third, as the participants were primarily healthy Asian adults, further studies to validate these effects in Western populations and other demographic groups are warranted.

Nevertheless, this review consolidates recent evidence on meal sequence interventions in healthy adults and highlights the fact that simply modifying the order of food intake may effectively attenuate postprandial glycemic variability. By adhering to the PRISMA guidelines, the review systematically performed literature search, study selection, and data extraction and compared results across diverse study designs and outcomes, thereby supporting the potential for clinical and public health applications. Future studies should strengthen the evidence base by using standardized protocols for meal composition consumption order and performing long-term RCTs that encompass diverse ages, ethnicities, and metabolic conditions.

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that meal sequence interventions may attenuate acute postprandial blood glucose responses in healthy adults. The effects were most evident when vegetables, fruits, or protein-rich foods were consumed before carbohydrate-rich foods and may be mediated by physiological mechanisms such as delayed gastric emptying, reduced intestinal glucose absorption, and enhanced incretin secretion. However, due to the short intervention durations, small sample sizes, and limited population diversity, the results should be interpreted as evidence of acute postprandial effects rather than long-term glycemic control or disease prevention. Future research should include large-scale, long-term RCTs across diverse populations and use standardized protocols to strengthen the evidence base and inform clinical and public health applications.

NOTES

-

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: SL. Methodology: SL, EHJ. Validation: SL, EHJ, JK. Formal analysis: JK. Investigation: JK. Data curation: JK. Writing - original draft: JK. Writing - review & editing: SL, EHJ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflicts of interest

Seungmin Lee is an editorial board member of this journal but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Data of this research is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary materials

Fig. 1.Flowchart of the study selection process.

Fig. 2.Risk-of-bias assessment of the included studies.

Table 1.

Table 1.

|

Criteria |

Determinant |

|

Population (P) |

Healthy adults |

|

Intervention (I) |

Meal Sequence |

|

Comparison (C) |

Healthy adults who received a general meal sequence |

|

Outcome (O) |

Blood glucose response and related hormones |

Table 2.Characteristics of the included studies

Table 2.

|

Study |

Design |

Subject (male:female) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Mean age (yr) |

Region |

Intervention |

Outcome variable |

Key finding |

|

Nagoro et al. [18] (2019) |

Randomized control trial |

Healthy adults 30 (12:18) |

C (n=6): 27.1±2.7 |

36.7±3.5 |

Indonesia |

Comparison of different meal sequence patterns (rice-only, rice-first, and vegetable-first) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

T1 (n=6): 23.2±1.9 |

|

Fruit- and vegetable-first consumption (T1, T3) resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose levels at 1 h compared with rice-first consumption (C) (P<0.001) |

|

T2 (n=6): 26.0±4.9 |

|

|

|

T3 (n=6): 25.2±3.4 |

|

|

|

T4 (n=6): 29.4±4.4 |

|

|

|

Nishino et al. [19] (2018) |

Randomized crossover |

Healthy adults 8 (4:4) |

20.30±1.10 |

20±1.2 |

Japan |

Comparison of different meal sequence patterns (carbohydrate-first, carbohydrate-last, and vegetable-first) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

Secondary outcome: serum insulin, HbA1c |

VMC resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose levels at 30 min compared with CVM (P<0.01); |

|

Serum glucose AUC₀-₁₂₀ tended to differ among the three meal sequence groups, with the highest values observed in the CVM and the lowest in the VMC |

|

Secondary outcome: |

|

VMC resulted in a significantly lower change in insulin level at 30 min compared with CVM (P<0.05); |

|

VMC resulted in significantly lower serum insulin AUC₀-₁₂₀ compared with CVM (P=0.0449) |

|

Sun et al. [20] (2020) |

Randomized crossover |

Healthy adults 16 (13:3): Chinese ethnic background |

22.0±2.0 |

25.8±4.8 |

Singapore |

Comparison of different meal sequence patterns (rice-first, meat-first, vegetable-first, mixed eating) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

Secondary outcome: serum insulin, GLP-1, GIP |

V-M-R resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose levels at 15, 30, and 45 min compared with mixed and rice-first consumption (VMR, R-VM) (P<0.05) |

|

Secondary outcome: |

|

V-MR and V-M-R resulted in significantly lower serum insulin concentrations at 30 min compared with R-VM (P<0.05); |

|

Mixed, meat-first, and rice-first (VMR, M-VR, R-VM) consumption resulted in significantly lower plasma total GLP-1 concentrations at 60 min compared with V-M-R consumption (P<0.05). |

|

Shaheen et al. [21] (2024) |

Randomized crossover |

Healthy adults 18 (7:11): Arab ethnicity (15), Emirati (3) |

25.4±2.3 |

31.1±8.6 |

United Arab Emirates |

Comparison of different sequence patterns (rice-last, mixed eating) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

Secondary outcome: serum insulin |

VPF resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose concentration in 30 min compared with SMM (P=0.001) |

|

Secondary outcome: |

|

Meal sequence did not result in significant differences in the insulinogenic index between the test meals |

|

Kurotobi et al. [22] (2025) |

Randomized crossover |

Healthy adults 29 (21:8) |

21.9±2.8 |

32.7±6.6 |

Japan |

Comparison of different meal sequence patterns (rice-last, mixed eating) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

Non–rice-first consumption (−5 dish, −10 dish, −15 dish) resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose levels over 4 hours compared with mixed and rice-first consumption (+15 dish, 0 dish) (P<0.05); |

|

Non–rice-first consumption (−15 beef) resulted in significantly lower 4-hour mean postprandial blood glucose compared with mixed eating (0 beef) (P<0.05) |

|

Matsuo et al. [23] (2023) |

Repeated measures |

Healthy adults 6 (3:3) |

20.8±1.5 |

21.3±0.5 |

Japan |

Comparison of different meal sequence patterns (rice-first, meat-first, vegetable-first, mixed eating) |

Primary outcome: blood glucose |

Primary outcome: |

|

Meat-first consumption (MVR) resulted in significantly lower postprandial blood glucose concentration at all measured time points except 120 min compared with other meal sequences (P<0.05); |

|

Vegetable-first consumption (VMR) did not result in significant differences in postprandial blood glucose concentrations at any time point except 90 min |

REFERENCES

- 1. Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res 2010;107:1058-70.

- 2. Ceriello A, Monnier L, Owens D. Glycaemic variability in diabetes: clinical and therapeutic implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:221-30.

- 3. Sun B, Luo Z, Zhou J. Comprehensive elaboration of glycemic variability in diabetic macrovascular and microvascular complications. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021;20:9.

- 4. Seuring T, Archangelidi O, Suhrcke M. The economic costs of type 2 diabetes: a global systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:811-31.

- 5. O’Connell JM, Manson SM. Understanding the economic costs of diabetes and prediabetes and what we may learn about reducing the health and economic burden of these conditions. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1609-11.

- 6. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidance on global monitoring for diabetes prevention and control: framework, indicators, and application. WHO; 2024.

- 7. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Summary of revisions: standards of care in diabetes–2025. Diabetes Care 2025;48(1 Suppl 1):S6-13.

- 8. Lindstrom J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia 2013;56:284-93.

- 9. Orozco LJ, Buchleitner AM, Gimenez-Perez G, Roque I, Figuls M, Richter B, Mauricio D. Exercise or exercise and diet for preventing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(3):CD003054.

- 10. Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1808-17.

- 11. Thomas D, Elliott EJ. Low glycaemic index, or low glycaemic load, diets for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2009:CD006296.

- 12. Liu AG, Most MM, Brashear MM, Johnson WD, Cefalu WT, Greenway FL. Reducing the glycemic index or carbohydrate content of mixed meals reduces postprandial glycemia and insulinemia over the entire day but does not affect satiety. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1633-7.

- 13. Park MH, Chung SJ, Shim JE, Jang SH, Nam KS. Effects of macronutrients in mixed meals on postprandial glycemic response. J Nutr Health 2018;51:31-9.

- 14. Kim JS, Nam K, Chung SJ. Effect of nutrient composition in a mixed meal on the postprandial glycemic response in healthy people: a preliminary study. Nutr Res Pract 2019;13:126-33.

- 15. Kubota S, Liu Y, Iizuka K, Kuwata H, Seino Y, Yabe D. A review of recent findings on meal sequence: an attractive dietary approach to prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2020;12:2502.

- 16. Lee CL, Shyam S, Lee ZY, Tan JL. Food order and glucose excursion in Indian adults with normal and overweight/obese body mass index: a randomised crossover pilot trial. Nutr Health 2021;27:161-9.

- 17. Parums DV. Editorial: review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Med Sci Monit 2021;27:e934475.

- 18. Satrio Nagoro D, Gunawan Tamtomo D, Indarto D. A randomized control trial related to meal order of fruit, vegetable and high glycaemic carbohydrate in healthy adults and its effects on blood glucose levels and waist circumference. Bali Med J 2019;8:247-54.

- 19. Nishino K, Sakurai M, Takeshita Y, Takamura T. Consuming carbohydrates after meat or vegetables lowers postprandial excursions of glucose and insulin in nondiabetic subjects. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2018;64:316-20.

- 20. Sun L, Goh HJ, Govindharajulu P, Leow MK, Henry CJ. Postprandial glucose, insulin and incretin responses differ by test meal macronutrient ingestion sequence (PATTERN study). Clin Nutr 2020;39:950-7.

- 21. Shaheen A, Sadiya A, Mussa BM, Abusnana S. Postprandial glucose and insulin response to meal sequence among healthy UAE adults: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2024;17:4257-65.

- 22. Kurotobi Y, Kuwata H, Matsushiro M, et al. Sequence of eating at Japanese-style set meals improves postprandial glycemic elevation in healthy people. Nutrients 2025;17:658.

- 23. Matsuo T, Higaki S, Inai R. Effect of intake order of rice, meat, and vegetables on postprandial blood glucose level in healthy young individuals. Tech Bull Fac Agric Kagawa Univ 2023;75:73-8.

- 24. Mao T, Huang F, Zhu X, Wei D, Chen L. Effects of dietary fiber on glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Funct Foods 2021;82:104500.

- 25. Lu K, Yu T, Cao X, et al. Effect of viscous soluble dietary fiber on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized clinical trials. Front Nutr 2023;10:1253312.

- 26. Giuntini EB, Sarda FA, de Menezes EW. The effects of soluble dietary fibers on glycemic response: an overview and futures perspectives. Foods 2022;11:3934.

- 27. Anjom-Shoae J, Feinle-Bisset C, Horowitz M. Impacts of dietary animal and plant protein on weight and glycemic control in health, obesity and type 2 diabetes: friend or foe? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024;15:1412182.

- 28. Ma J, Stevens JE, Cukier K, et al. Effects of a protein preload on gastric emptying, glycemia, and gut hormones after a carbohydrate meal in diet-controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1600-2.

- 29. Ekberg NR, Catrina SB, Spegel P. A protein-rich meal provides beneficial glycemic and hormonal responses as compared to meals enriched in carbohydrate, fat or fiber, in individuals with or without type-2 diabetes. Front Nutr 2024;11:1395745.