ABSTRACT

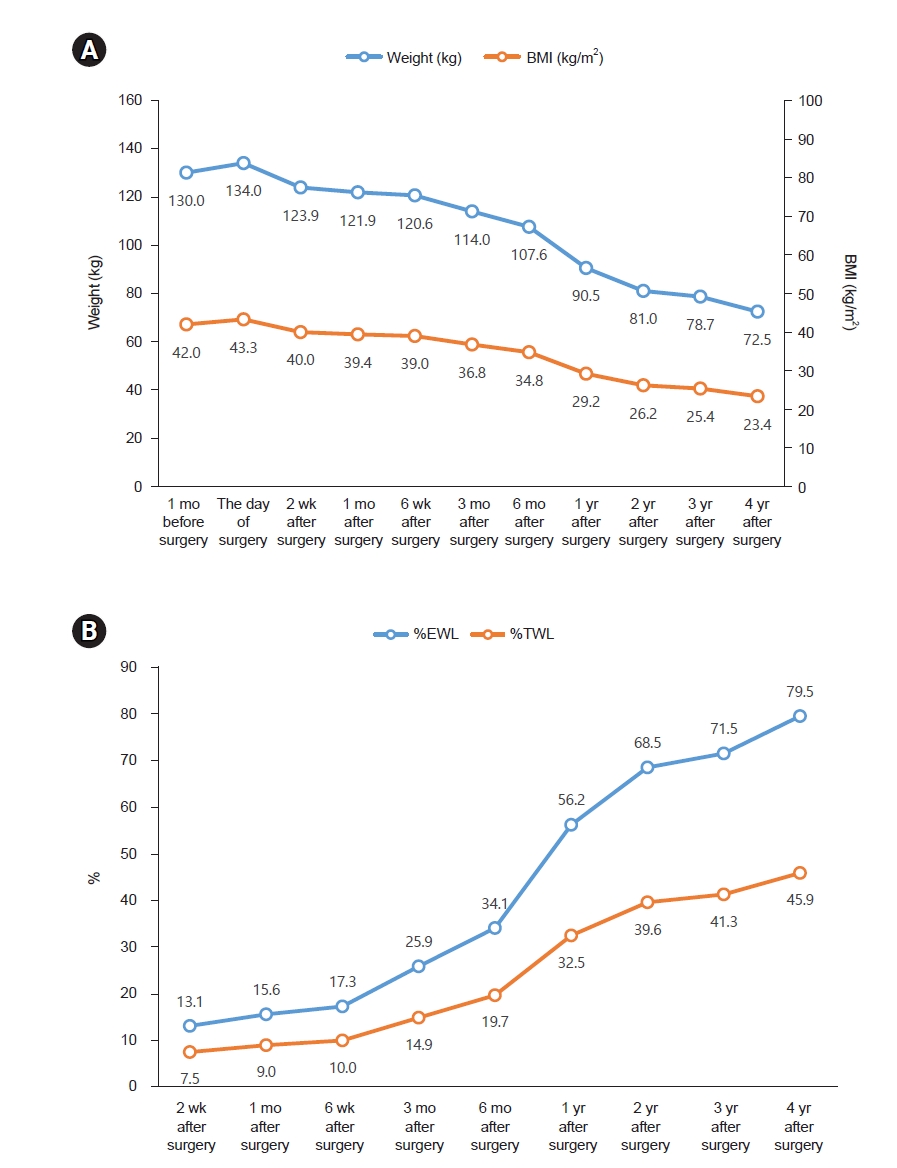

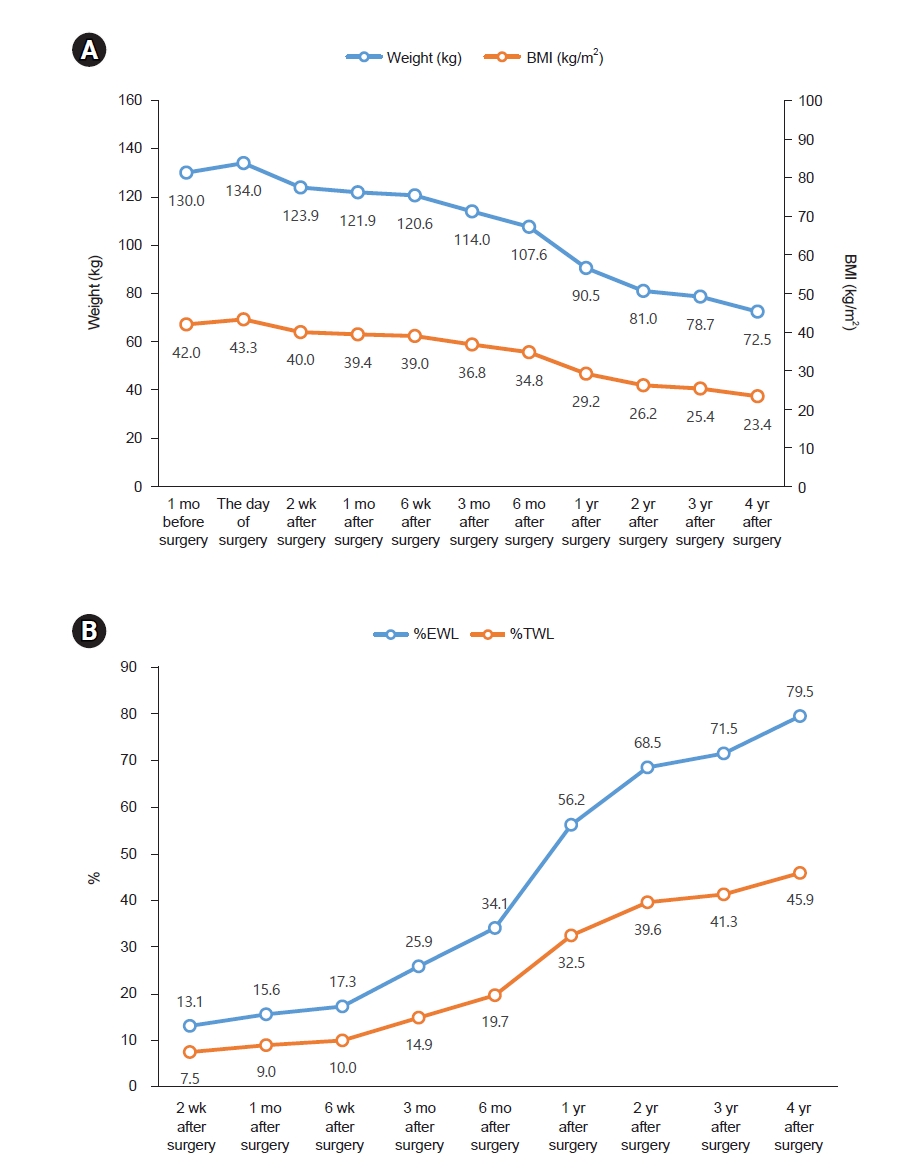

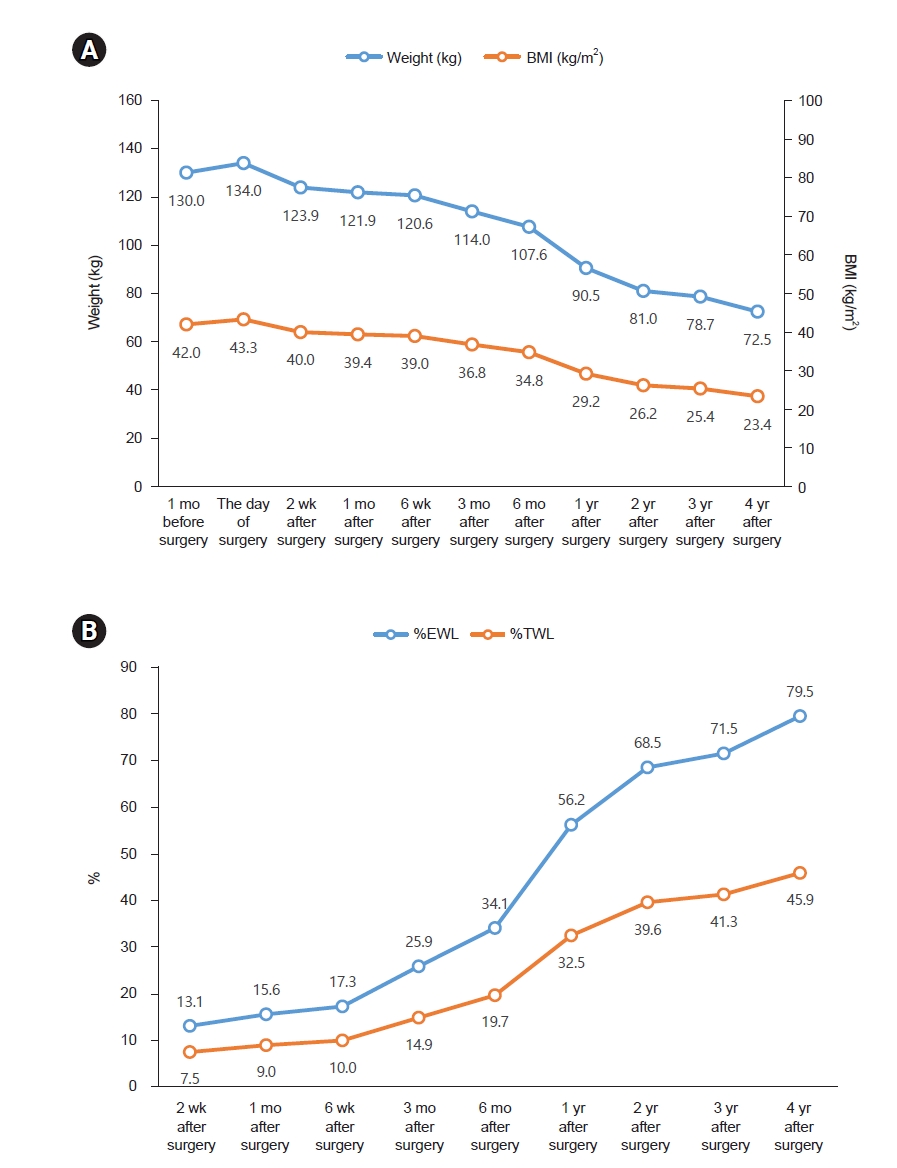

This case report describes the nutritional management and long-term outcomes of an adolescent undergoing bariatric surgery. A 13-year-old female patient with morbid obesity complicated by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) underwent sleeve gastrectomy in July 2021. The patient achieved significant weight loss, with a body mass index decreasing from 42.0 to 23.4 kg/m2 and reaching a total weight loss of 45.9% by the fourth postoperative year. Remission of NASH, IGT, and PCOS was observed after 1 year. Postoperatively, vitamin D deficiency developed, whereas other biochemical parameters remained within normal reference ranges. Adherence to recommended nutritional supplementation was suboptimal; however, with continuous nutritional education and regular follow-up, the patient ultimately established and maintained a balanced dietary pattern. The case highlights the effectiveness of bariatric surgery in achieving sustained weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities in adolescents, while underscoring the critical role of continuous nutritional management, patient education, and individualized multidisciplinary care in supporting long-term postoperative success.

-

Keywords: Bariatric surgery; Diet, Food, and Nutrition; Adolescent; Case reports

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity among adolescents has increased steadily worldwide, accompanied by a rising burden of obesity-related comorbidities, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes (T2D), insulin resistance, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Bariatric surgery has emerged as an effective therapeutic option for adolescents with morbid obesity. According to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, bariatric surgery is indicated in adolescents with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥35 kg/m

2 or ≥120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex with significant comorbidities, such as OSA, T2D, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), or hypertension, or in those with a BMI of ≥40 kg/m

2 [

1]. At our institution, bariatric surgery is performed in adolescents with a BMI of ≥35 kg/m

2 or a BMI of ≥30 kg/m

2 with accompanying comorbidities, after confirmation of completed skeletal growth.

Following bariatric surgery, adolescents are at risk for various nutrition-related complications resulting from alterations in the gastrointestinal tract and postoperative dietary restrictions. These complications include vomiting, anorexia, altered bowel habits, and dumping syndrome. Accordingly, a structured postoperative dietary progression from liquids to a regular diet, combined with ongoing counseling by a clinical dietitian, is essential to reduce symptoms and prevent nutritional deficiencies. In addition, sustained lifestyle modifications play a central role in achieving effective weight loss and long-term weight maintenance, underscoring the importance of ongoing nutritional management [

2-

4]. Previous studies have reported postoperative deficiencies in key nutrients, including protein, vitamin B

12, folate, vitamin D, calcium, and iron. However, most available evidence is derived from adult populations, and data specific to adolescents remain limited [

5].

Currently, evidence-based guidelines for nutritional management in adolescent bariatric patients are lacking, largely due to insufficient empirical data. This case report aims to describe the nutritional interventions implemented in an adolescent undergoing bariatric surgery, evaluate clinical and nutritional outcomes, and share practical experience. By doing so, this report seeks to contribute to the body of evidence and support the development of standardized nutritional management strategies for adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital with a waiver of informed consent (No. 3-2025-0318).

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 13-year-old girl diagnosed with morbid obesity complicated by NASH, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and amenorrhea secondary to PCOS. At the preoperative evaluation, her height was 175.9 cm, body weight was 130 kg, and BMI was 42.0 kg/m2. Despite previous attempts at weight loss through dietary modification, exercise, and traditional herbal medicine, she did not achieve clinically meaningful weight loss. Preoperative assessment of the epiphyseal growth plates confirmed completion of bone growth. Based on her BMI and associated comorbidities, she met the institutional criteria for adolescent bariatric surgery and subsequently underwent sleeve gastrectomy in July 2021.

Nutritional management provided by the clinical dietitian at the Gangnam Severance Hospital is outlined in

Table 1. The patient received nutritional counseling during outpatient visits for approximately 30 minutes at each outpatient visit, scheduled at 2 weeks and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery, followed by annual follow-up visits. Counseling focused on diet monitoring, nutrient adequacy, eating behaviors, physical activity, and long-term adherence to lifestyle modifications. Biochemical, anthropometric, and dietary intake data were collected longitudinally from the preoperative period through 4 years postoperatively using medical records and interviews. To ensure consistency, all dietary assessments were conducted by the same clinical dietitian using the 24-hour recall method, supported by food models to improve portion size estimation. Energy and protein intakes were calculated manually using the food exchange lists for Koreans [

6]. Preoperative and postoperative biochemical parameters are summarized in

Table 2. Postoperatively, the patient developed vitamin D deficiency, defined as a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D

3 level below 20 ng/mL [

4], while other biochemical parameters remained within the reference ranges. Changes in anthropometric measures following bariatric surgery are presented in

Fig. 1, and longitudinal trends in energy and protein intake are presented in

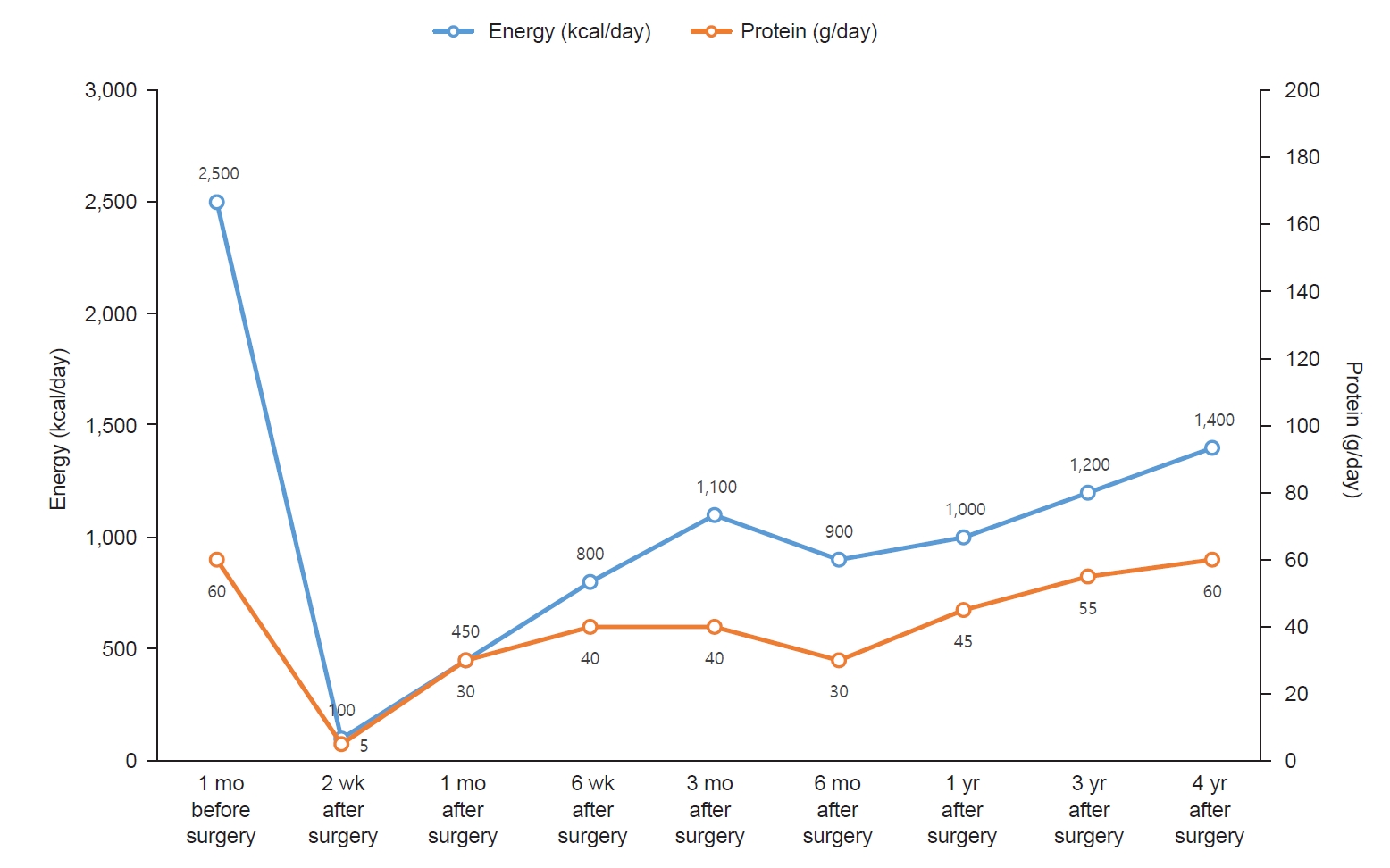

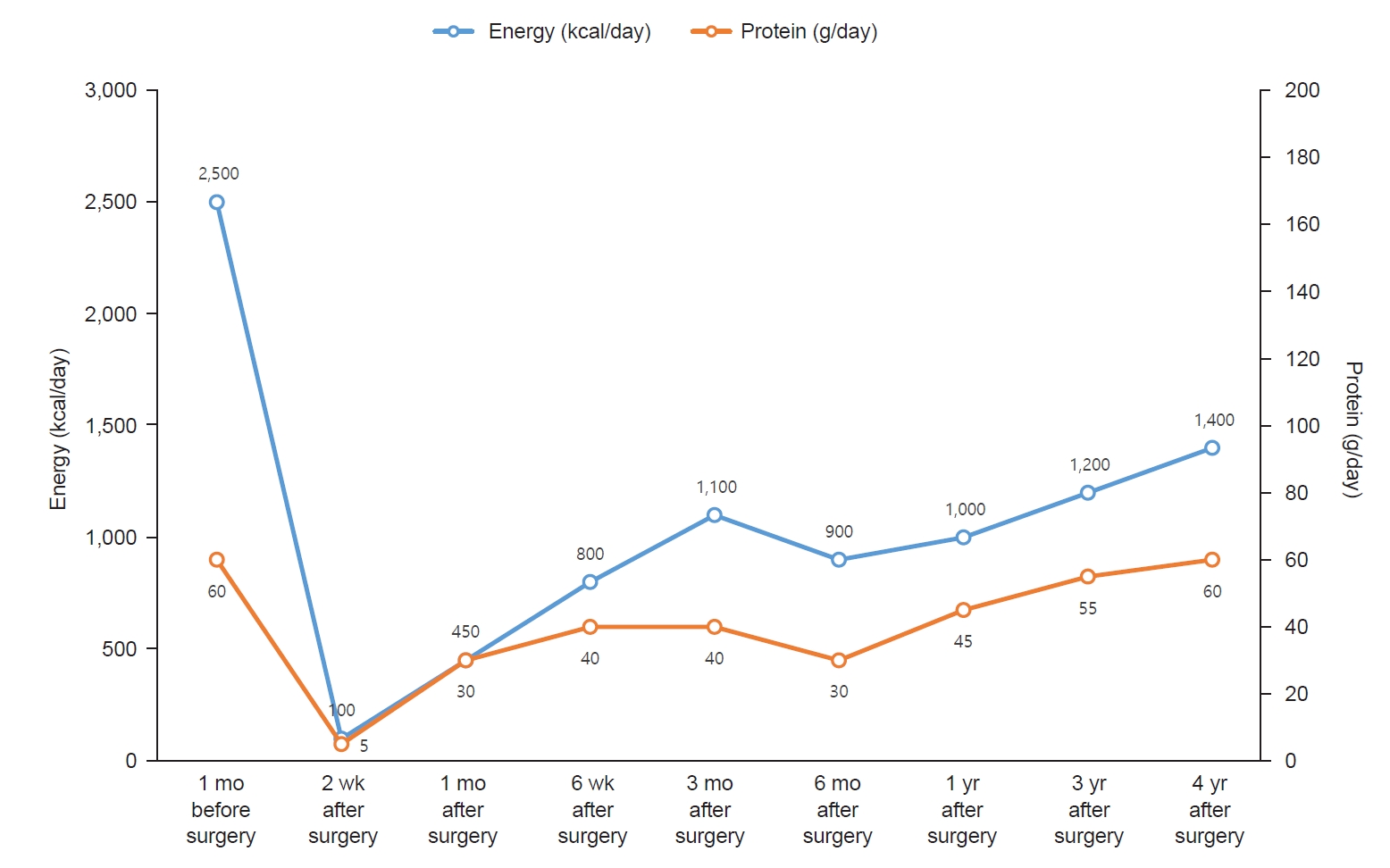

Fig. 2.

One month before surgery, the patient reported consuming three meals per day with an estimated total daily energy intake of 2,500 kcal. Her dietary pattern was characterized by frequent snacking, regular consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, and a preference for fast food. During the preoperative nutritional assessment, the patient was educated on the role of dietary modification and caloric reduction in preoperative weight management and surgical preparedness.

Admission for surgery

Despite the preoperative goal of weight reduction, the patient gained 4 kg before surgery, increasing the BMI from 42.0 to 43.3 kg/m2. She underwent sleeve gastrectomy on July 26, 2021. The patient was maintained on nothing by mouth on the day of surgery and on postoperative day (POD) 1. Sips of water were initiated on POD 2, followed by a clear liquid diet on POD 3 and advancement to a full liquid diet on POD 4. The patient was discharged on POD 5. On POD 4, the clinical dietitian provided education regarding post-discharge dietary management, including continuing a full liquid diet until the first outpatient follow-up visit, guidance on protein and micronutrient supplementation, and strategies for managing postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms, including dumping syndrome, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.

Two weeks post-surgery

Two weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency room with dizziness and was admitted for evaluation and management. Following discharge, her reported energy intake was approximately 100 kcal per day due to intolerance to the prescribed liquid diet and limited acceptance of available options. Nutritional counseling was reinforced to emphasize the importance of adherence to the liquid diet during the early postoperative period. Alternative liquid food options were suggested to improve tolerance and caloric intake. The patient was subsequently discharged.

One month post-surgery

One month after surgery, the patient advanced prematurely to a regular diet despite prior instructions to maintain a soft diet. This prompted re-education on appropriate dietary modifications to prevent complications. By the first postoperative month, the patient had achieved a weight loss of 9.0%, approaching the target of 10% total weight loss (TWL).

Six weeks post-surgery

Six weeks after surgery, the patient was adhering to a soft diet and was advised to gradually transition to a regular diet. However, her protein intake was insufficient at 40 g/day. Despite recommendations for protein supplements, she reported poor tolerance related to personal preferences. Consequently, she was counseled to consume soft, protein-rich foods, such as eggs and tofu. Additionally, she was encouraged to initiate regular exercise.

Three months post-surgery

Three months after surgery, the patient reported consuming three meals per day. Each meal included 30 to 40 g of rice and half a serving of protein. Snacks primarily included dairy products and fruits, with occasional consumption of chips or fast food. The estimated daily energy intake was approximately 1,100 kcal. The patient had initiated a routine of walking for 30 minutes daily after lunch. By 3 months after surgery, the patient achieved a TWL of 14.9%, which was below the target of 20%. Accordingly, the patient was advised to reduce snack intake and increase the intensity of physical activity.

Six months post-surgery

Six months after surgery, the patient had increased portion sizes at her three main meals to approximately 100 g of rice and one serving of protein per meal while eliminating all snacks. Consequently, her estimated total daily energy intake decreased to approximately 900 kcal. The patient continued her 30-minute walking regimen. She was advised to maintain the current dietary pattern and exercise routine.

One year post-surgery

One year post-surgery, the patient relocated to Canada, leading to changes in her dietary patterns and physical activity levels. Her typical breakfast included half a bowl of cereal with milk, lunch consisted of half a sandwich, and dinner comprised one to two servings of protein with vegetables. Physical activity included daily 30-minute walks and participation in Taekwondo sessions twice weekly. By the 1-year follow-up, the patient had achieved a TWL of 32.5%, exceeding the target of 30%. She was encouraged to continue her current dietary pattern and exercise regimen.

Three years post-surgery

Three years post-surgery, the patient reported consuming three meals per day, each approximating 1/2 to 1/3 of a standard school meal serving. Additionally, she consumed one to two eggs daily as snacks. The patient participated in supervised personal training sessions two to three times per week, each lasting 1 hour. She was advised to maintain her current dietary and exercise habits.

Four years post-surgery

Four years post-surgery, the patient had increased meal portions to 2/3 of a standard school meal serving per meal and eliminated snacks. She discontinued personal training and instead engaged in walking for approximately 30 minutes after lunch. She was advised to maintain her current dietary pattern and physical activity routine. Over the 4-year postoperative period, the patient achieved a TWL of 57.5 kg, with body weight reducing from 130 to 72.5 kg and BMI decreasing from 42.0 to 23.4 kg/m2. Despite initial difficulty in adjusting to the post-surgical diet, the patient ultimately established a balanced and sustainable eating pattern. At 1 year after surgery, follow-up assessments demonstrated remission of NASH and IGT, and the menstrual cycle had resumed regularity. The patient developed vitamin D deficiency after surgery. Although supplementation was recommended, she reported frequent nonadherence. Annual bone mineral density assessments were conducted, and all results remained within the normal reference range.

DISCUSSION

In this case study, the patient achieved a TWL of 41.3% and a BMI reduction of 16.6 kg/m

2 by 3 years after surgery, which increased to 18.6 kg/m

2 by the 4th year. These outcomes are consistent with previous research findings. The Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS) study, a large multicenter prospective cohort of adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery, reported a mean TWL of 27% over the first 3 years, corresponding to a BMI reduction of 13 kg/m

2 [

7]. Similarly, Alqahtani et al. [

8] reported a mean BMI reduction of 17.9 kg/m

2 at ≥4 years following sleeve gastrectomy in children and adolescents.

Long-term studies indicate that weight regain occurs in approximately 50% of patients after bariatric surgery [

9]. Data from the Teen-LABS cohort suggest that adolescents typically experience a significant weight loss of approximately 30% in the first postoperative year, followed by a gradual and modest weight regain, resulting in a sustained reduction of 22% to 27% at 5 years [

10]. In contrast, our patient demonstrated a remarkably stable and progressive weight loss over 4 years. This favorable trajectory appears to be closely related to consistent postoperative follow-up and repeated nutritional counseling, which supported the development of structured eating habits, portion control, and sustained lifestyle modification.

Furthermore, the patient experienced remission of NASH, IGT, and PCOS by the fourth year post-surgery. Previous studies have demonstrated high remission rates for comorbidities such as T2D (90.0%), dyslipidemia (76.6%), hypertension (80.7%), OSA (80.8%), and asthma (92.5%) after at least 5 years of follow-up [

11]. These findings highlight the metabolic benefits of bariatric surgery in adolescents and reinforce its role as an effective intervention not only for weight reduction but also for the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities.

Despite these benefits, bariatric surgery is associated with an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies, particularly in adolescent patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported postoperative nutrient deficiencies, with prevalence rates of low serum levels of albumin, ferritin, vitamin D, and vitamin B

12 of 10%, 49%, 41%, and 20%, respectively. Additionally, 23% of adolescents experienced iron deficiency, and 10% developed calcium deficiency [

5]. Another study reported that the most common postoperative deficiencies in adolescents were vitamin D (92.3%), albumin (51.8%), anemia (15.9%), zinc (11.1%), and vitamin B

12 (8.0%) [

12]. Our patient developed vitamin D deficiency post-surgery, whereas other nutritional parameters remained within normal ranges. The etiology of vitamin D deficiency following bariatric surgery is multifactorial and includes preoperative baseline deficiency, inadequate supplementation, and malabsorption related to altered bile salt metabolism, potential intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and the anatomical redirection of the small intestine [

13]. Although vitamin D supplementation was recommended by the clinical dietitian, adherence was poor. A previous study reported high rates of nonadherence to vitamin supplementation following adolescent bariatric surgery, with common barriers including forgetfulness and difficulty swallowing pills [

14]. Consistent with these findings, our patient also demonstrated poor adherence to pre-surgery weight loss efforts, a liquid diet in the early postoperative phase, and protein and vitamin supplementation. However, with ongoing education and repeated nutritional counseling, the patient ultimately established and maintained a balanced dietary pattern. These observations underscore the importance of ongoing education, close monitoring, and individualized support to improve adherence and achieve long-term success after adolescent bariatric surgery.

This study is limited by its design as a single case report involving only one patient, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the detailed longitudinal follow-up provides meaningful insight into the nutritional challenges and adherence issues that may emerge at different postoperative stages. Future studies with larger adolescent cohorts, as well as comparative analyses between adolescent and adult populations, are needed to better delineate age-related differences in surgical outcomes, nutritional deficiencies, and optimal postoperative care.

In conclusion, a multidisciplinary approach is essential for adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery. Continuous nutritional management and individualized care are critical to achieving durable weight loss, preventing nutritional deficiencies, and maintaining long-term adherence to postoperative treatment guidelines.

NOTES

-

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: YY, HL, SMA. Data curation: YY. Investigation: YY. Visualization: YY. Writing–original draft: YY. Writing–review & editing: YYY, HL, SMA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflicts of interest

Hosun Lee is an editorial board member of this journal, but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Data of this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Fig. 1.Anthropometric changes after bariatric surgery. (A) Changes in weight and BMI. (B) Changes in %EWL and %TWL. BMI, body mass index; %EWL, excess weight loss=[(initial weight−postoperative weight)/(initial weight−ideal weight)]×100; %TWL, total weight loss=(initial weight−postoperative weight)/initial weight×100.

Fig. 2.Changes in energy and protein intake.

Table 1.Standard dietary progression following bariatric surgery at Gangnam Severance Hospital

Table 1.

|

Periods after surgery |

Recommended type of foods |

Recommended nutrient intake |

|

Preoperative period |

Balanced low-calorie diet |

Energy: |

|

Female: 1,200–1,500 kcal |

|

Male: 1,500–1,800 kcal |

|

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

|

Very low-calorie diet when BMI >45 kg/m2

|

Energy: 600–800 kcal |

|

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

|

Until 2 wk |

Liquid diet |

Energy: 600–800 kcal |

|

Allowed: gruel, soup, soymilk, yogurt, liquid protein supplements, oral nutritional supplements |

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

|

2–4 wk |

Pureed diet |

Energy: 800–1,000 kcal |

|

Allowed: porridge added protein sources and vegetables, soft protein foods (eggs and tofu) |

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

|

4–6 wk |

Soft diet |

Energy: 800–1,000 kcal |

|

Allowed: protein foods (fish and meat), soft vegetables |

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

|

After 6 wk |

Balanced regular diet |

Energy: 1,000–1,400 kcal |

|

Most foods are allowed, but it is recommended to avoid foods high in fat and sugar |

Protein: 60–80 g/day |

Table 2.Biochemical profiles before and after bariatric surgery

Table 2.

|

Biochemical parameter |

1 mo before surgery |

Day of surgery |

Duration after surgery |

|

2 wk |

1 mo |

3 mo |

6 mo |

1 yr |

2 yr |

3 yr |

|

Hematological marker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

11.9 |

11.4 |

14.2 |

12.7 |

12.3 |

13.6 |

11.6 |

12.4 |

11.7 |

|

Hematocrit (%) |

35.9 |

34.9 |

44.7 |

39.8 |

39.3 |

42.6 |

36.6 |

38.3 |

35.6 |

|

Iron (μg/dL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

134 |

117 |

112 |

131 |

134 |

|

Ferritin (ng/mL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

81.7 |

98.0 |

22.5 |

31.1 |

17.3 |

|

TIBC (μg/dL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

327 |

356 |

331 |

314 |

321 |

|

Vitamins and minerals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vitamin B1 (nmol/L) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4.1 |

5.6 |

2.9 |

10.9 |

4.6 |

|

Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

673 |

508 |

339 |

332 |

397 |

|

Folate (ng/mL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3.8 |

4.0 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.4 |

|

25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 (ng/mL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

11.6 |

10.7 |

20.0 |

- |

12.5 |

|

PTH (pg/mL) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

36.2 |

37.1 |

|

Calcium (mg/dL) |

8.7 |

8.2 |

9.6 |

9.3 |

9.7 |

10.1 |

8.8 |

9.5 |

9.2 |

|

Phosphorus (mg/dL) |

3.6 |

3.5 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

5.9 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

3.8 |

|

Metabolic and lipid profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fasting glucose (mg/dL) |

69 |

133 |

92 |

84 |

84 |

87 |

76 |

78 |

79 |

|

HbA1c (%) |

5.9 |

- |

- |

- |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

4.9 |

|

Insulin (μU/mL) |

56.6 |

- |

- |

- |

30.7 |

47.6 |

12.0 |

- |

11.5 |

|

C-peptide (ng/mL) |

5.36 |

- |

- |

- |

3.36 |

4.66 |

2.84 |

- |

1.88 |

|

Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

161 |

153 |

246 |

167 |

181 |

187 |

133 |

142 |

133 |

|

LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) |

106 |

- |

- |

- |

136 |

136 |

78 |

62 |

75 |

|

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) |

30 |

- |

- |

- |

35 |

35 |

41 |

49 |

47 |

|

Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

120 |

- |

- |

- |

105 |

120 |

72 |

60 |

45 |

|

AST (U/L) |

37 |

110 |

68 |

106 |

38 |

24 |

13 |

12 |

12 |

|

ALT (U/L) |

67 |

155 |

142 |

92 |

52 |

27 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

|

Blood pressure (mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systolic |

132 |

140 |

114 |

120 |

- |

102 |

- |

121 |

103 |

|

Diastolic |

70 |

70 |

87 |

60 |

- |

50 |

- |

54 |

59 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Pratt JS, Browne A, Browne NT, et al. Asmbs pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery guidelines, 2018. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14:882-901.

- 2. Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, Craggs-Dino L, Isom KA, Greiman L. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery integrated health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient 2016 update: micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:727-41.

- 3. Handzlik-Orlik G, Holecki M, Orlik B, Wylezol M, Dulawa J. Nutrition management of the post-bariatric surgery patient. Nutr Clin Pract 2015;30:383-92.

- 4. Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:O1-58.

- 5. Zolfaghari F, Khorshidi Y, Moslehi N, Golzarand M, Asghari G. Nutrient deficiency after bariatric surgery in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2024;34:206-17.

- 6. Cho JW, Ju DL, Lee Y, et al. Korean food exchange lists for diabetes meal planning: revised 2023. Clin Nutr Res 2024;13:227-37.

- 7. Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, et al.; Teen-LABS Consortium. Weight loss and health status 3 years after bariatric surgery in adolescents. N Engl J Med 2016;374:113-23.

- 8. Alqahtani AR, Elahmedi M, Abdurabu HY, Alqahtani S. Ten-year outcomes of children and adolescents who underwent sleeve gastrectomy: weight loss, comorbidity resolution, adverse events, and growth velocity. J Am Coll Surg 2021;233:657-64.

- 9. Halloun R, Weiss R. Bariatric surgery in adolescents with obesity: long-term perspectives and potential alternatives. Horm Res Paediatr 2022;95:193-203.

- 10. Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, et al.; Teen–LABS Consortium. Five-year outcomes of gastric bypass in adolescents as compared with adults. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2136-45.

- 11. Wu Z, Gao Z, Qiao Y, et al. Long-term results of bariatric surgery in adolescents with at least 5 years of follow-up: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2023;33:1730-45.

- 12. Elhag W, El Ansari W. Multiple nutritional deficiencies among adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery: who is at risk? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;18:413-24.

- 13. Lespessailles E, Toumi H. Vitamin D alteration associated with obesity and bariatric surgery. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242:1086-94.

- 14. Modi AC, Zeller MH, Xanthakos SA, Jenkins TM, Inge TH. Adherence to vitamin supplementation following adolescent bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:E190-5.