ABSTRACT

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of almond consumption on serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). An electronic database search was performed on PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library from inception through October 2024. Summary effect size measurements were calculated using random effects model estimation and were reported as weighted mean differences (WMDs) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A total of 258 articles were identified, and 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The meta-analysis of eleven RCTs, which involved a total of 544 participants, indicated that almonds significantly reduced levels of CRP (WMD, −0.28 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.52, −0.04; p = 0.02). However, we found no significant benefit of almond consumption in improving serum MDA levels, and due to the limited number of studies, the examination of MDA was conducted only qualitatively. This study supports the conclusion that almond consumption has favorable effects on CRP levels in individuals with CVD risk factors. More high-quality trials are needed to confirm these findings.

-

Keywords: Almond; Inflammation; C-reactive protein; Oxidative stress; Systematic review; Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death, and disability worldwide, affecting both men and women [

1]. In 2019, it accounted for approximately one-third of global deaths [

2]. Unhealthy eating habits and physical inactivity are key lifestyle factors that significantly contribute to the development of CVD [

3,

4]. Additionally, inflammation is a major metabolic factor involved in the development and progression of CVD [

5]. Inflammation represents a physiological response instigated by the immune system to address biological, chemical, and physical stimuli and cellular and molecular occurrences [

6,

7]. Chronic inflammation plays a significant role in host defenses against injury and infection, but it also contributes to the pathophysiology of several other chronic diseases including arthritis, asthma, autoimmune diseases, kidney disorders, cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome and mental disorders [

5,

8]. C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor-α are recognized as key biomarkers of inflammatory processes in the human body [

9]. Many factors, such as nutrition, infections, psychological stress, and genetics, greatly impact inflammation [

10,

11,

12]. Considering the concerns mentioned above, controlling and reducing inflammatory markers can help prevent chronic diseases and is essential for every health system. Anti-inflammatory medications can be effective in reducing inflammation; however, their side effects may limit their overall effectiveness in treating persistent inflammation [

13]. Recently, there has been increasing interest in functional foods and herbal ingredients for managing inflammatory markers, primarily due to their low side effects and greater availability [

14,

15].

Nuts have been extensively studied in various research projects and are recognized as part of a healthy diet. Due to their nutritional content, nuts may help reduce inflammation in the body [

16]. Among nuts, almonds are particularly regarded as one of the best anti-inflammatory options [

16]. Almonds are the edible seeds of the fruit of the almond tree and contain several bioactive compounds that influence the body's physiological and metabolic functions [

17]. The fatty acid composition in almonds is notably high, with about 90% of their lipid content consisting of oleic acid (a monounsaturated fat) and linoleic acid (a polyunsaturated fat) [

17]. In addition to healthy fats, almonds are a good source of flavonoids, protein, dietary fiber, and essential vitamins, especially Vitamin E and several B vitamins [

17]. Recent meta-analyses indicate that almond consumption can improve CVD risk factors, including blood pressure, glycemic indices, lipid profiles, and anthropometric measures, while also reducing oxidative stress [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Although clinical trials regarding the anti-inflammatory effects of almond consumption have been published, the conclusions of these studies are not always consistent. Some studies indicate that almond consumption lowers levels of inflammatory substances [

23,

24]. Conversely, other studies have failed to demonstrate this effect [

25,

26]. Furthermore, some meta-analyses [

16,

27,

28] have reported the benefits of almond intake on inflammatory markers. However, most of these studies included both healthy and unhealthy individuals, and none specifically focused on the effects of almonds on inflammatory biomarkers in individuals with CVD risk factors.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to assess the effects of almonds on serum levels of CRP and malondialdehyde (MDA) in individuals with CVD risk factors. This review aims to offer valuable insights into clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines [

29].

To carry out this study, a comprehensive search strategy was implemented to identify relevant published studies. Electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, were searched from their inception until October 2024. The search keywords used were (“Almonds” OR “Prunus dulcis”) AND (“inflammation” OR “inflammatory biomarkers” OR “C-reactive protein” OR “CRP” OR “high-sensitivity C-reactive protein” OR “hs-CRP” OR “oxidative stress” OR “malondialdehyde” OR “MDA”). No language or time restrictions were applied to the search strategy. Additionally, we manually searched all relevant references in articles to identify potentially applicable RCTs. Only published studies were considered.

Study selection

Two independent authors (M.E and L.Kh) conducted the study selection process. In cases of disagreement, a third author (E.F.M) was consulted, or a consensus was reached. After removing duplicates using EndNote software (EndNote X6; Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA), the selection of studies was carried out in three stages. First, the titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed to eliminate irrelevant publications. Next, the remaining articles underwent a full-text review. The following criteria were used to select RCTs for inclusion in this meta-analysis: (a) the study design was either parallel or crossover; (b) the target population consisted of individuals with CVD risk factors; (c) the intervention group received almonds; and (d) the RCTs provided information regarding the mean changes in CRP and MDA levels, along with the standard deviation (SD) for both the intervention and control groups. Studies involving children, adolescents, pregnant women, or lactating women were excluded. Additionally, studies that examined almonds in combination with other interventions, which prevented the assessment of the isolated effect of almonds, as well as studies with an intervention duration of less than one week, were excluded. RCTs that did not report mean changes or mean differences between the intervention and placebo groups, as well as abstracts from conferences without full-text data, were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two authors (M.E and L.Kh), covering various aspects such as publication details (including the last name of the first author, study location, publication year, total sample size, and study design), population characteristics (mean age, gender, and health status), interventions (follow-up period, types and dosages of almonds and control groups), and outcomes. In this meta-analysis, only the highest dose or duration of almond intervention was examined, even when studies reported effects at different doses or durations. Data extraction discrepancies were primarily resolved through consensus or expert consultation (E.F.M). If the study did not report the desired information, we emailed the corresponding author to obtain it.

Quality assessment

The two reviewers, M.E and L.Kh, independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Handbook risk of bias tool [

30]. Their evaluation was based on several criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, handling of incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential sources of bias. Each of these criteria was classified as having either a low risk, high risk, or unclear risk of bias. After completing the assessments, each RCT was ultimately rated as having poor, fair, or good quality. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (E.F.M).

All analyses were conducted using the random-effects model with STATA software (version 11.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). For each trial, the weighted mean difference (WMD) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and presented in a forest plot. In studies where net changes were not directly reported for the intervention and control groups, the effect size was calculated by subtracting the post-intervention measurement from the pre-intervention values. The SD of the mean differences was determined using the formula: SD = square root [{SD pre-treatment}2 + {SD post-treatment}2 – {2 × R × SD pre-treatment × SD post-treatment}]. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, where an I2 value of 50% or greater indicated significant heterogeneity. To analyze the effects of almond consumption under various conditions, we performed subgroup analyses based on the participants' age, study design, and trial duration. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding individual studies one at a time to evaluate their effect on the overall results of the meta-analysis. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot asymmetry and Egger's test, and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Articles identification

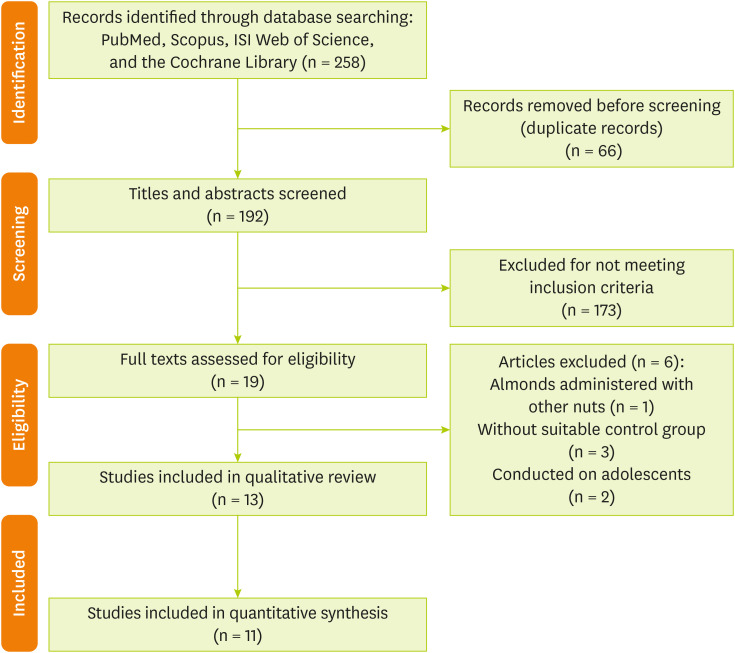

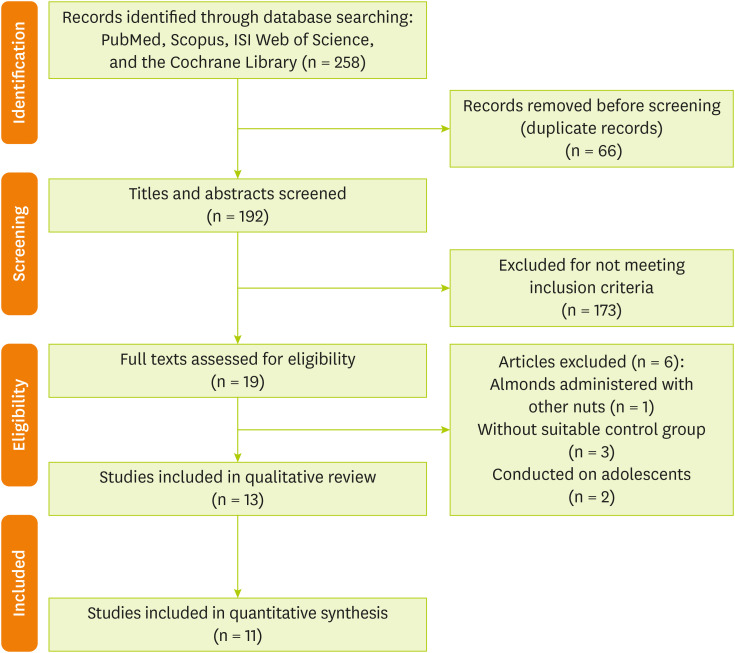

The database searches resulted in 258 studies. After eliminating duplicates, a total of 192 records remained. By screening the titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, an additional 173 studies were removed. Among the 19 full-text articles evaluated for eligibility, 6 were excluded for the following reasons: the studies lacked a suitable control group, examined almonds mixed with other nuts, or were conducted on adolescents. Ultimately, 13 articles [

23,

26,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The results of the literature search are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1Flow diagram of included and excluded studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The present study included thirteen RCTs [

23,

26,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] with a total of 635 participants. The sample sizes of the studies varied significantly, ranging from 20 to 128 individuals. Among these studies, nine [

23,

26,

31,

33,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] utilized a crossover design while four [

32,

34,

35,

41] employed a parallel design, with publication dates spanning from 2002 to 2024. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States [

26,

31,

38,

39,

40,

41], and the remaining studies were conducted in Taiwan [

23,

33], Australia [

32,

34], Canada [

36], South Korea [

37], and India [

35]. All studies included participants of both sexes, with the average age ranging from 46 to 65 years. The almond dosages in the studies varied from 42.5 to 85 g/day, and the duration of the interventions lasted between 4 weeks and 28 weeks. The participants represented a range of subjects, including patients with T2DM, individuals with prediabetes, those with coronary artery disease, and participants who were overweight, obese or had lipid disorders. Data on CRP levels from two studies [

35,

40] could not be converted into statistical variables for meta-analysis and were only reported qualitatively. In total, 11 studies [

23,

26,

31,

32,

33,

34,

36,

37,

38,

39,

41] were included in the analysis. Detailed baseline information for all the included studies is provided in

Table 1.

Table 1Baseline characteristics of included studies

Table 1

|

Studies |

Region |

Sample size |

Design |

Sex |

Mean age (yr) |

Duration (wk) |

Subjects |

Intervention (daily dose, g/day) |

Control |

Outcome |

|

Jenkins et al. (2002) [36] |

Canada |

27 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

64 |

4 |

Hyperlipidemic subjects |

73 |

Muffins |

CRP |

|

Liu et al. (2013) [23] |

Taiwan |

20 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

58 |

12 |

T2D patients |

56 |

Isocaloric NCEP step II diet |

CRP, MDA |

|

Sweazea et al. (2014) [41] |

United States |

21 |

RCT parallel |

Male/female |

56 |

12 |

T2D patients |

43 |

Control typical diet |

CRP |

|

Berryman et al. (2015) [31] |

United States |

48 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

50 |

6 |

Adults with elevated LDL-cholesterol |

42.5 |

Isocaloric muffin+butter |

CRP |

|

Chen et al. (2015) [26] |

United States |

45 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

62 |

22 |

Coronary artery disease patients |

85 |

NCEP step 1 diet |

CRP |

|

Chen et al. (2017) [33] |

Taiwan |

33 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

55 |

28 |

T2D patients |

60 |

NCEP step 2 diet |

CRP |

|

Lee et al. (2017) [38] |

United States |

31 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

46 |

4 |

Overweight and obese individuals |

42.5 |

Isocaloric average American diet |

CRP |

|

Jung et al. (2018) [37] |

South Korea |

84 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

52 |

4 |

Overweight or obese participants |

56 |

Isocaloric cookies |

CRP, MDA |

|

Bowen et al. (2019) [32] |

Australia |

74 |

RCT parallel |

Male/female |

61 |

8 |

Adults with elevated risk of T2D or T2D |

56 |

Biscuit snack |

CRP |

|

Palacios et al. (2020) [39] |

United States |

33 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

48 |

6 |

Overweight or obese adults with prediabetes |

85 |

Carbohydrate-based foods |

CRP |

|

Coates et al. (2020) [34] |

Australia |

128 |

RCT parallel |

Male/female |

65 |

12 |

Overweight and obese adults |

15% Energy |

Nut-free diet |

CRP |

|

Gulati et al. (2023) [35] |

India |

66 |

RCT parallel |

Male/female |

42 |

13 |

Adults with prediabetes |

60 |

Standard diet |

CRP |

|

Siegel et al. (2024) [40] |

United States |

25 |

RCT crossover |

Male/female |

35 |

8 |

Overweight individuals |

57 |

Unsalted pretzels |

CRP |

Assessment of study quality

The Cochrane Handbook's risk of bias tool assessments indicated that three clinical trials [

23,

36,

40] studies were rated as fair quality, while others [

26,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

37,

38,

39,

41] were rated as high quality. Details regarding the quality assessment of the studies are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2Quality assessment of included studies based on Cochrane guidelines

Table 2

|

Studies |

Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants, personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective outcome reporting |

Other sources of bias |

|

Jenkins et al. (2002) [36] |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Liu et al. (2013) [23] |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Sweazea et al. (2014) [41] |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Berryman et al. (2015) [31] |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Chen et al. (2015) [26] |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Chen et al. (2017) [33] |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Lee et al. (2017) [38] |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Jung et al. (2018) [37] |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Bowen et al. (2019) [32] |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Palacios et al. (2020) [39] |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Coates et al. (2020) [34] |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Gulati et al. (2023) [35] |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Siegel et al. (2024) [40] |

Low |

High |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Results of the systematic review

Two studies [

35,

40] were reviewed qualitatively, indicating almond consumption had no significant impact on CRP levels. Research on the effects of almond consumption on serum MDA levels has only been reported in two studies [

23,

37]. Both studies concluded that eating almonds or following a diet that includes almonds does not significantly affect MDA levels.

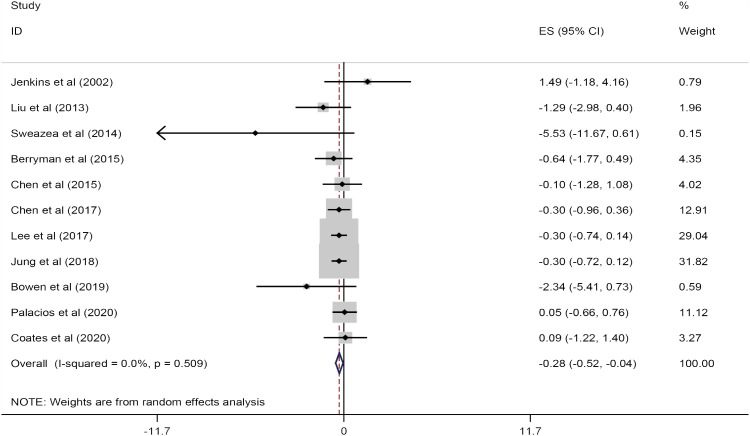

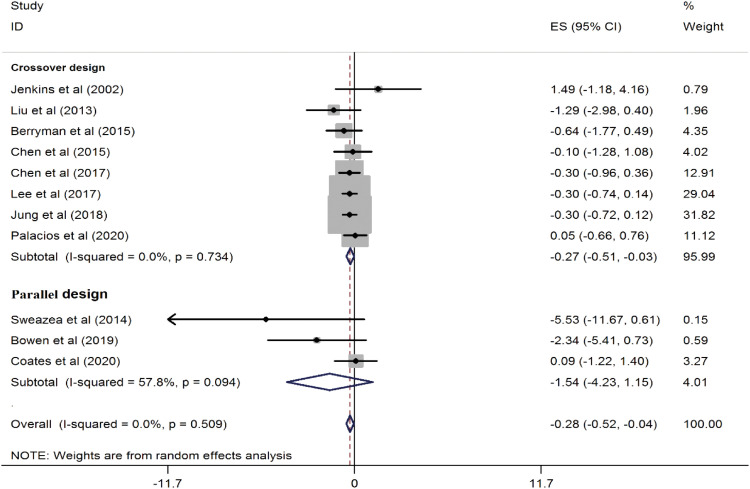

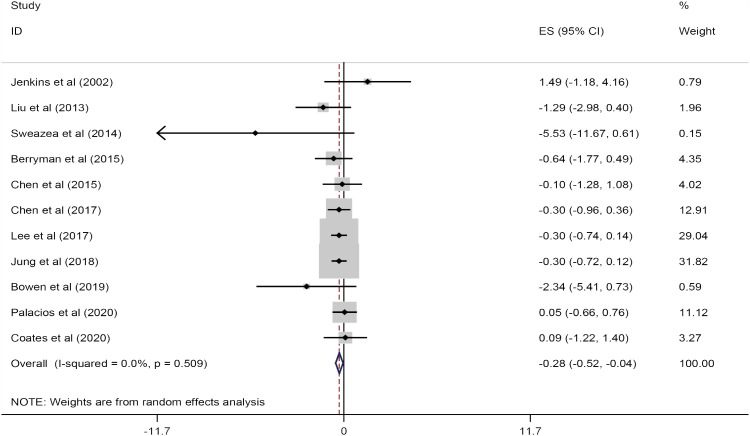

A total of 11 trials involving 544 participants were included in this meta-analysis. The combined results from these studies showed that almond consumption can improve CRP concentrations (WMD, −0.28 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.52, −0.04; p = 0.02) compared to a control group. There was no significant heterogeneity observed between the studies (I

2 = 0.0%; p = 0.50) (

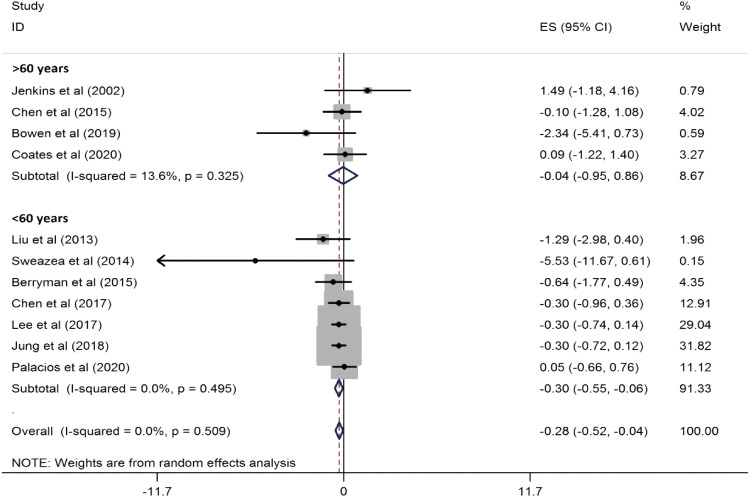

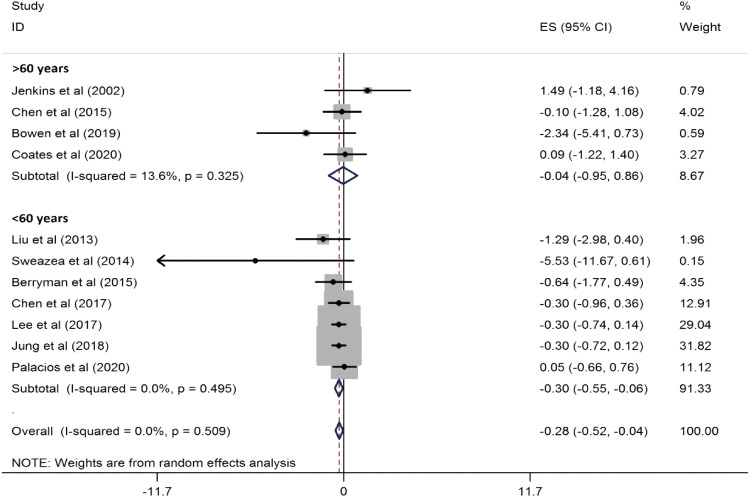

Figure 2). Subgroup analysis revealed that almond consumption significantly reduced serum CRP levels in the crossover design (WMD, −0.27 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.51, −0.03; p = 0.02) (

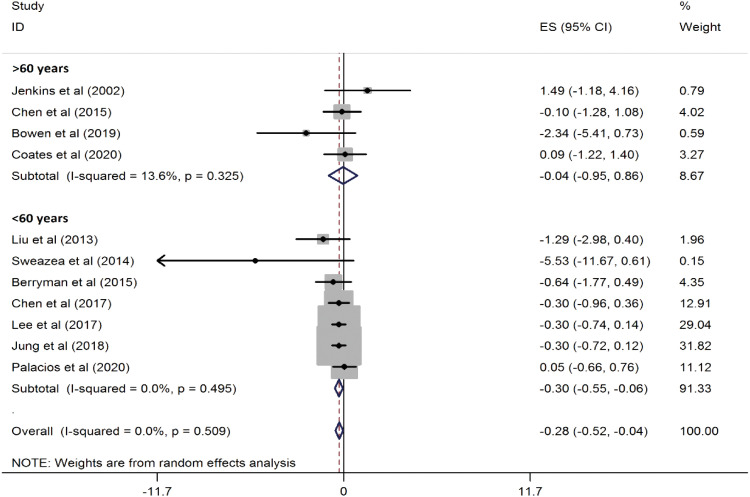

Figure 3). Additionally, in participants under the age of 60, the reduction was even more pronounced (WMD, −0.30 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.55, −0.06; p = 0.01) (

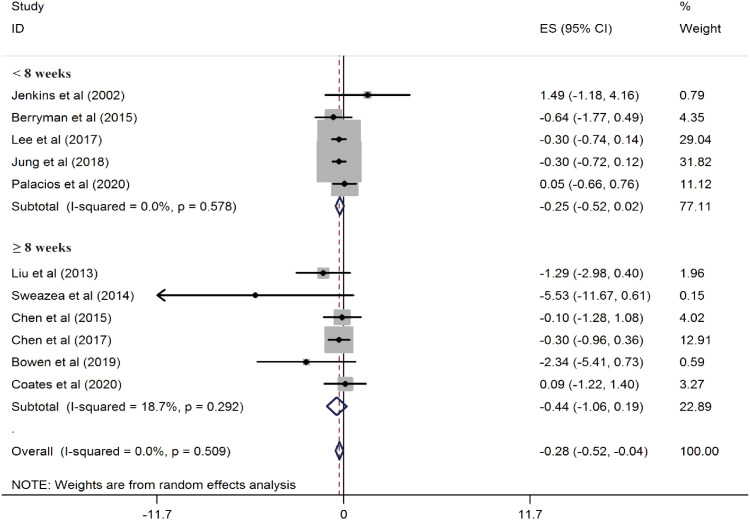

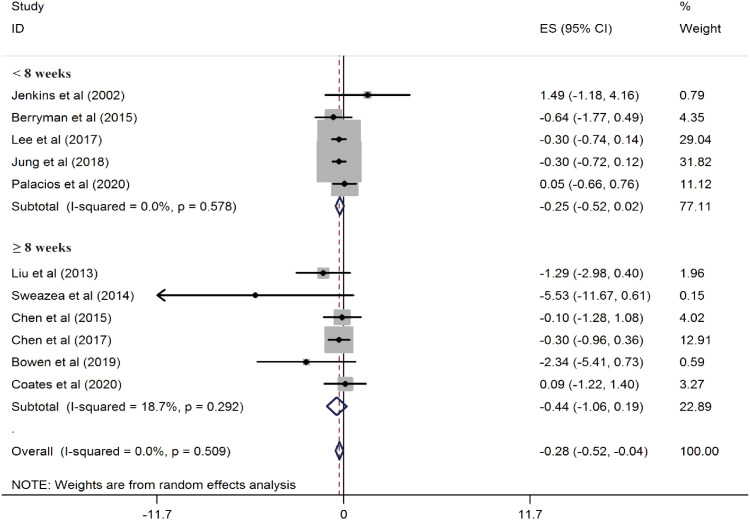

Figure 4). However, when the studies were classified by duration, the results became non-significant in both subsets (

Figure 5).

Figure 2

Forest plots showing the effect of almond consumption on serum C-reactive protein levels.

ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3

Forest plots showing the effect of almond consumption on serum C-reactive protein levels, categorized by study design.

ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4

Forest plots showing the effect of almond consumption on serum C-reactive protein levels, categorized by participants' mean age.

ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 5

Forest plots showing the effect of almond consumption on serum C-reactive protein levels, categorized by study duration.

ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

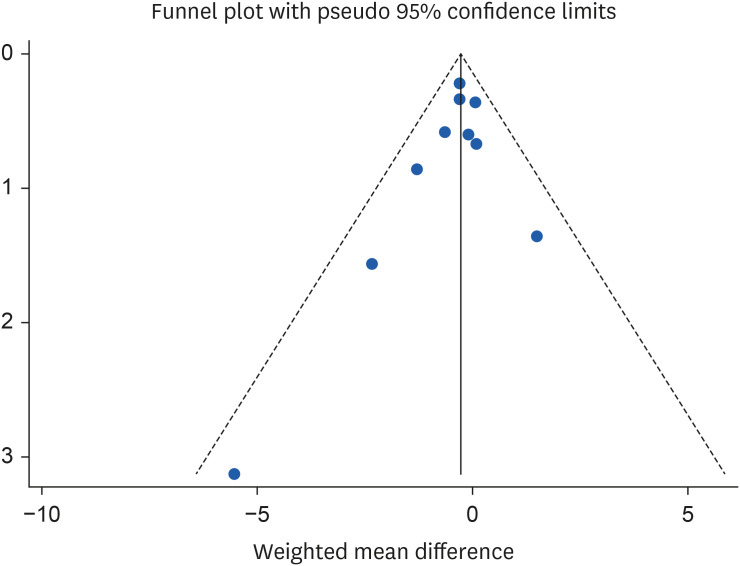

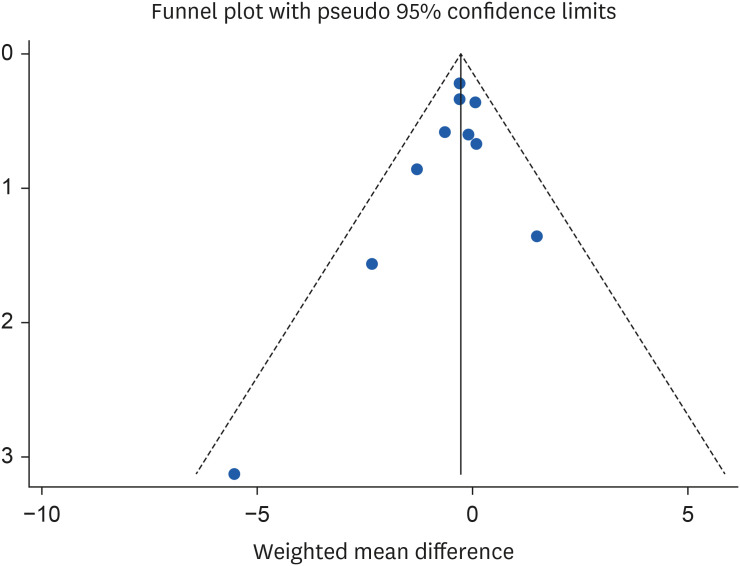

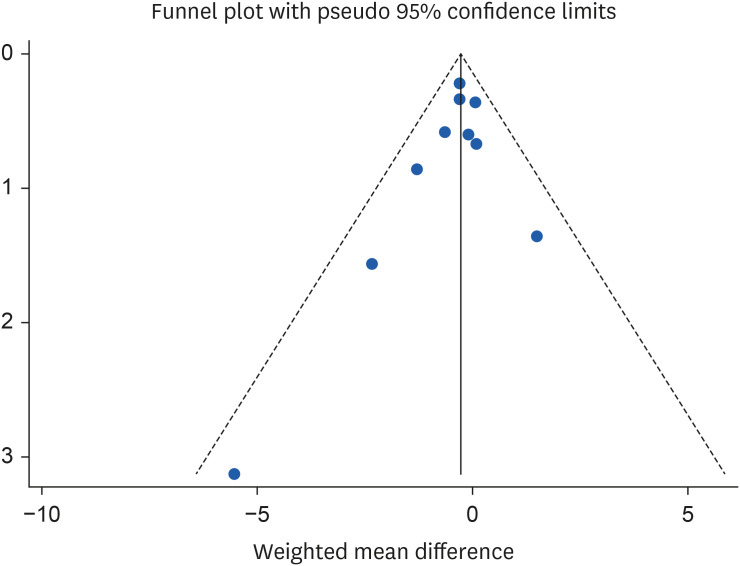

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that by excluding the studies of Lee et al. [

38] (WMD, −0.27 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.56, 0.01) and Jung et al. [

37] (WMD, −0.27 mg/L; 95% CI, −0.56, 0.02) the significant effect of almond consumption on serum CRP levels becomes non-significant. Because of the limited number of studies included in the analysis, Egger’s test was utilized to evaluate publication bias. The results from funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s regression asymmetry test showed no evidence of publication bias for the studies investigating the impact of almond consumption on CRP, with a p value of 0.30 (

Figure 6).

Figure 6Funnel plots for the studies of the effects of almond consumption on serum concentration of C-reactive protein.

DISCUSSION

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that almond consumption resulted in better effects on serum CRP levels in individuals with CVD risk factors compared to the control group. However, these results were not very robust when studies were excluded one by one. Additionally, we observed no benefit of almond consumption in improving serum MDA levels. Due to the limited number of studies, MDA was only examined qualitatively. In the subgroup analysis based on the study design, almond consumption significantly impacted CRP concentrations in trials with a crossover design, while the results for parallel trials were not significant. This may be attributed to the fact that crossover studies are generally more powerful than parallel studies. In addition, the number of crossover studies was nearly three times greater than that of parallel studies (8 vs. 3). Studies with crossover designs also employed a higher dose of almonds, which could explain why a significant reduction in CRP was observed only in the crossover subset. In a subgroup analysis based on participants' mean age, almond consumption significantly affected CRP concentrations in trials with participants under 60 years old. However, the results showed no significant impact for participants over 60 years old. Moreover, when stratifying the studies by the duration of the intervention, the results in both subgroups became non-significant. This discrepancy could be due to the small number of studies in each subgroup. As is statistically evident, the reliability of results often depends on sample size. Although no statistical heterogeneity was found among the studies in this analysis, the results should still be interpreted with caution.

In recent years, several meta-analyses have examined the relationship between almond consumption and inflammatory markers. The results of our study align with the findings by Fatahi et al. [

16], which indicated that consuming almonds leads to a significant reduction in CRP levels. However, our results differ from other meta-analyses [

22,

27,

28,

42] that explored the effects of almond consumption on inflammatory markers in adults or individuals with diabetes, which concluded that almonds do not significantly improve CRP levels. The discrepancy in findings may stem from variations in the number of studies included in each meta-analysis or differences in the populations studied. Individuals at risk for CVD such as those who are obese, and have diabetes, often have higher CRP levels and may be more responsive to nutritional interventions aimed at reducing this biomarker [

43,

44].

The exact mechanism of almonds on the inflammation is still unclear. However, several mechanisms may explain the beneficial effects of almond consumption on CRP levels. Almonds, along with other nuts, are rich in magnesium [

16], which has been shown in previous meta-analyses to reduce inflammatory factors, particularly CRP [

45]. Magnesium deficiency can activate phagocytes, enhance oxidative bursts in granulocytes, stimulate endothelial cells, and increase cytokine levels, all contributing to inflammation [

46]. The high magnesium content in almonds may help lower inflammatory markers by influencing various metabolic processes and boosting the production of nitric oxide [

45]. Additionally, almonds contain a significant amount of omega-3 fatty acids, which are known for their effectiveness in reducing inflammation and are recognized as strong anti-inflammatory agents [

16]. Research has also indicated that the phytochemical content in almonds can improve antioxidant levels, thereby reducing inflammation [

16,

22]. Almonds are a rich source of antioxidants, particularly vitamin E and polyphenols. These compounds help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. Additionally, almonds are high in unsaturated fatty acids, which also contribute to lowering oxidative stress [

21,

23,

33]. High levels of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) cause inflammation in endothelial cells, leading to dysfunction and eventually cell death. The antioxidant properties of almonds may influence NF-κB levels, which regulate genes related to inflammation [

27,

47]. Furthermore, obesity is associated with increased inflammation and higher CRP levels. Studies have suggested that almonds can positively impact body measurements, and by aiding in the management of obesity, they may contribute to reduced inflammation [

48,

49]. Almonds may help modulate intestinal microbial flora due to their content of short-chain fatty acids, which could improve CRP levels and oxidative stress [

49,

50].

When evaluating the results of this study and applying them in a clinical context, it is important to consider the limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis. Despite our significant efforts to improve the methodology of this paper, several notable limitations have impacted on the findings. First, the total number of RCTs included in the study was small, which reduces the statistical power and accuracy of the results. Second, nearly half of the studies were conducted in the United States, limiting the applicability of the conclusions to other geographical areas. Third, CRP levels were reported as a secondary outcome in most studies, leading to the possibility that confounding factors that may have influenced the results were not controlled. Additionally, since all studies included participants of both sexes, we were unable to analyze the impact of gender on the results. Finally, the protocol for this study was not registered on the Prospero website, which can also be considered a limitation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that consuming almonds may have beneficial effects on serum CRP levels in individuals with CVD risk factors. However, RCTs have not demonstrated a significant impact of almond consumption on improving MDA levels. To further confirm the health benefits associated with almond consumption, more high-quality and rigorously designed trials are needed.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Data curation: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Formal analysis: Fazeli Moghadam E.

Investigation: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Methodology: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Project administration: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Resources: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Software: Fazeli Moghadam E.

Supervision: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Validation: Eslami M.

Visualization: Eslami M.

Writing - original draft: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

Writing - review & editing: Eslami M, Khaghani L, Fazeli Moghadam E.

REFERENCES

- 1. Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. Magnussen C, Ojeda FM, Leong DP, Alegre-Diaz J, et al. Global effect of modifiable risk factors on cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1273-1285.

- 2. Yang J, Zhang Y, Na X, Zhao A. β-Carotene supplementation and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2022;14:1284.

- 3. Shan Z, Li Y, Baden MY, Bhupathiraju SN, Wang DD, et al. Association between healthy eating patterns and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1090-1100.

- 4. Ignarro LJ, Balestrieri ML, Napoli C. Nutrition, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease: an update. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:326-340.

- 5. Henein MY, Vancheri S, Longo G, Vancheri F. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:12906.

- 6. Bennett JM, Reeves G, Billman GE, Sturmberg JP. Inflammation–nature’s way to efficiently respond to all types of challenges: implications for understanding and managing “the epidemic” of chronic diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:316.

- 7. Chovatiya R, Medzhitov R. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol Cell 2014;54:281-288.

- 8. Moradi S, Hadi A, Mohammadi H, Asbaghi O, Zobeiri M, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and the risk of frailty among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Aging 2021;43:323-331.

- 9. Askari G, Aghajani M, Salehi M, Najafgholizadeh A, Keshavarzpour Z, et al. The effects of ginger supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Herb Med 2020;22:100364.

- 10. Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:901-912.

- 11. Demetrowitsch TJ, Schlicht K, Knappe C, Zimmermann J, Jensen-Kroll J, et al. Precision nutrition in chronic inflammation. Front Immunol 2020;11:587895.

- 12. Al Bander Z, Nitert MD, Mousa A, Naderpoor N. The gut microbiota and inflammation: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7618.

- 13. Bindu S, Mazumder S, Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: a current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol 2020;180:114147.

- 14. Mohammadi H, Hadi A, Kord-Varkaneh H, Arab A, Afshari M, et al. Effects of ginseng supplementation on selected markers of inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res 2019;33:1991-2001.

- 15. Askarpour M, Karimi M, Hadi A, Ghaedi E, Symonds ME, et al. Effect of flaxseed supplementation on markers of inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine 2020;126:154922.

- 16. Fatahi S, Daneshzad E, Lotfi K, Azadbakht L. The effects of almond consumption on inflammatory biomarkers in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv Nutr 2022;13:1462-1475.

- 17. Özcan MM. A review on some properties of almond: ımpact of processing, fatty acids, polyphenols, nutrients, bioactive properties, and health aspects. J Food Sci Technol 2023;60:1493-1504.

- 18. Eslampour E, Asbaghi O, Hadi A, Abedi S, Ghaedi E, et al. The effect of almond intake on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med 2020;50:102399.

- 19. Lee-Bravatti MA, Wang J, Avendano EE, King L, Johnson EJ, et al. Almond consumption and risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr 2019;10:1076-1088.

- 20. Asbaghi O, Moodi V, Hadi A, Eslampour E, Shirinbakhshmasoleh M, et al. The effect of almond intake on lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct 2021;12:1882-1896.

- 21. Luo B, Mohammad WT, Jalil AT, Saleh MM, Al-Taee MM, et al. Effects of almond intake on oxidative stress parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement Ther Med 2023;73:102935.

- 22. Ojo O, Wang XH, Ojo OO, Adegboye ARA. The effects of almonds on gut microbiota, glycometabolism, and inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrients 2021;13:3377.

- 23. Liu JF, Liu YH, Chen CM, Chang WH, Chen CY. The effect of almonds on inflammation and oxidative stress in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized crossover controlled feeding trial. Eur J Nutr 2013;52:927-935.

- 24. Gulati S, Misra A, Pandey RM. Effect of almond supplementation on Glycemia and cardiovascular risk factors in Asian Indians in North India with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 24-week study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2017;15:98-105.

- 25. Hou YY, Ojo O, Wang LL, Wang Q, Jiang Q, et al. A randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of peanuts and almonds on the cardio-metabolic and inflammatory parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2018;10:1565.

- 26. Chen CY, Holbrook M, Duess MA, Dohadwala MM, Hamburg NM, et al. Effect of almond consumption on vascular function in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized, controlled, cross-over trial. Nutr J 2015;14:61.

- 27. Hariri M, Amirkalali B, Baradaran HR, Gholami A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of almond effect on C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in adults. Complement Ther Med 2023;72:102911.

- 28. Morvaridzadeh M, Qorbani M, Shokati Eshkiki Z, Estêvão MD, Mohammadi Ganjaroudi N, et al. The effect of almond intake on cardiometabolic risk factors, inflammatory markers, and liver enzymes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res 2022;36:4325-4344.

- 29. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71.

- 30. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928.

- 31. Berryman CE, West SG, Fleming JA, Bordi PL, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of daily almond consumption on cardiometabolic risk and abdominal adiposity in healthy adults with elevated LDL-cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e000993.

- 32. Bowen J, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Stonehouse W, Tran C, Rogers GB, et al. Effects of almond consumption on metabolic function and liver fat in overweight and obese adults with elevated fasting blood glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2019;30:10-18.

- 33. Chen CM, Liu JF, Li SC, Huang CL, Hsirh AT, et al. Almonds ameliorate glycemic control in Chinese patients with better controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trial. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2017;14:51.

- 34. Coates AM, Morgillo S, Yandell C, Scholey A, Buckley JD, et al. Effect of a 12-week almond-enriched diet on biomarkers of cognitive performance, mood, and cardiometabolic health in older overweight adults. Nutrients 2020;12:1180.

- 35. Gulati S, Misra A, Tiwari R, Sharma M, Pandey RM, et al. Premeal almond load decreases postprandial glycaemia, adiposity and reversed prediabetes to normoglycemia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023;54:12-22.

- 36. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, Parker TL, Connelly PW, et al. Dose response of almonds on coronary heart disease risk factors: blood lipids, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a), homocysteine, and pulmonary nitric oxide: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Circulation 2002;106:1327-1332.

- 37. Jung H, Chen CO, Blumberg JB, Kwak HK. The effect of almonds on vitamin E status and cardiovascular risk factors in Korean adults: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Nutr 2018;57:2069-2079.

- 38. Lee Y, Berryman CE, West SG, Chen CO, Blumberg JB, et al. Effects of dark chocolate and almonds on cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals: a randomized controlled‐feeding trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005162.

- 39. Palacios OM, Maki KC, Xiao D, Wilcox ML, Dicklin MR, et al. Effects of consuming almonds on insulin sensitivity and other cardiometabolic health markers in adults with prediabetes. J Am Coll Nutr 2020;39:397-406.

- 40. Siegel L, Rooney J, Marjoram L, Mason L, Bowles E, et al. Chronic almond nut snacking alleviates perceived muscle soreness following downhill running but does not improve indices of cardiometabolic health in mildly overweight, middle-aged, adults. Front Nutr 2024;10:1298868.

- 41. Sweazea KL, Johnston CS, Ricklefs KD, Petersen KN. Almond supplementation in the absence of dietary advice significantly reduces C-reactive protein in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Funct Foods 2014;10:252-259.

- 42. Moosavian SP, Rahimlou M, Rezaei Kelishadi M, Moradi S, Jalili C. Effects of almond on cardiometabolic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res 2022;36:1839-1853.

- 43. Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2013;14:232-244.

- 44. Stanimirovic J, Radovanovic J, Banjac K, Obradovic M, Essack M, et al. Role of C‐reactive protein in diabetic inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2022;2022:3706508.

- 45. Veronese N, Pizzol D, Smith L, Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. Effect of magnesium supplementation on inflammatory parameters: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2022;14:679.

- 46. Maier JA, Castiglioni S, Locatelli L, Zocchi M, Mazur A. Magnesium and inflammation: advances and perspectives. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2021;115:37-44.

- 47. Adebayo AA, Oboh G, Ademosun AO. Effect of dietary inclusion of almond fruit on sexual behavior, arginase activity, pro-inflammatory, and oxidative stress markers in diabetic male rats. J Food Biochem 2021;45:e13269.

- 48. Eslampour E, Moodi V, Asbaghi O, Ghaedi E, Shirinbakhshmasoleh M, et al. The effect of almond intake on anthropometric indices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Funct 2020;11:7340-7355.

- 49. Dreher ML. A comprehensive review of almond clinical trials on weight measures, metabolic health biomarkers and outcomes, and the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2021;13:1968.

- 50. McLoughlin RF, Berthon BS, Jensen ME, Baines KJ, Wood LG. Short-chain fatty acids, prebiotics, synbiotics, and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:930-945.